On the Biggest Collection of Fantasy Tales Since WWII

Ann and Jeff VanderMeer Preview The Big Book of Modern Fantasy

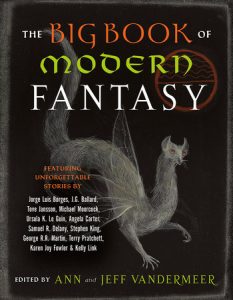

Fantasy, like any form of fiction or mode of fiction, can contain multitudes. At least, that is what we found when researching and compiling The Big Book of Modern Fantasy. In one sense, our task was made easier by the sheer immensity of the project: at 500,000 words, our anthology is the single largest post-WWII collection of fantasy stories ever published.

However, that word, “multitudes,” made some of the decisions very difficult. Because one thing you discover as editors is a depth and richness to fantasy fiction that truly staggers the imagination. Nascent and early fantasy as collected in our prior The Big Book of Classic Fantasy felt like a simpler task due to the amount of time that has passed to let classics and hidden gems come to the surface and lesser works to fade. Although our usual self-imposed ten-year cut-off date—2010, in this case—does help provide necessary perspective.

The logic behind our process for The Big Book of Modern Fantasy meant continuing to explore humor in a fantasy vein in the modern volume while also including a surprising number of stories directly relevant to the politics and social questions of the age. (Perhaps in some sense the cliché of fantasy as escapist is out of date, given the evidence.) While there are in the final table of contents plenty of stories about dragons, there are also a fair number of stories detailing the “secret life of objects.”

Many of these tales reboot or update the idea of the folktale or fairytale while grappling with modern issues. For example, Argentine writer Sara Gallardo’s “The Great Night of Trains” features characters that are trains, but is really about revolution. And not to be outdone, on the talking creature side, a real gem like Guyanese writer Edgar Mitteholzer’s “Poolwana’s Orchid” isn’t just about insects and plants that converse. It’s about prejudice, greed regret, and friendship.

As anthologists covering wide subjects like “fantasy,” you want your stories to have weight, you want them to mean something. To be relevant to a modern audience when possible. But another anchor is, of course, the sheer sense of play that pervades many of these tales. Maurice Richardson’s “Ten Rounds with Grandfather Clock” is, although tinged with satire, at heart just simply a surrealist hilarity about a boxing match with a clock. Does it need to be more? Or Terry Pratchett’s “Troll Bridge,” which takes a humorous (but loving) jab at the entire fairy tale genre.

Some stories you become so fond of you just love them unconditionally by the end of the process. Most of them are stories that held up to your re-reads over and over, while revealing something new every time. “The Youngest Doll” by Puerto Rican writer Rosario Ferré, is a cautionary story told in a manner familiar to readers of fairy tales. Published almost five decades ago, it still resonates today with its commentary on women’s rights and income equality.

“Five Letters From an Eastern Empire,” by Scottish writer Alasdair Gray is playful in its telling, yet biting in the satire in how it portrays government officials and organized religion. Ramsey Shehadeh’s “Creature” is a favorite of ours, introducing a horrifying yet friendly monster, described so joyfully, who takes a young girl under their protection and helps her navigate through a post-apocalyptic future amid the destruction perpetrated by humankind.

The truth is, a book of modern fantasy is a treasure trove of marvels, a cabinet of curiosities, and, perhaps more importantly, a strong, strong testimony to the importance of imaginative literature, of non-realist literature, and of traditions other than the Anglo Saxon. We, personally, have been enriched by these stories and lifted up by them. We hope readers will find their own favorites and fond memories from reading herein.

*

The anthology’s table of contents is below. If unnoted, the contributor’s country of origin is the US or UK.

Dean Francis Alfar, “The Kite of Stars” (Philippines)

Erik Amundsen, “Bufo Rex”

J.G. Ballard, “The Drowned Giant”

Nathan Ballingrud, “The Malady of Ghostly Cities”

Greg Bear, “The White Horse Child”

Aimee Bender, “End of the Line”

Jorge Luis Borges, “The Zahir” (Argentina), translated by Andrew Hurley

Richard Bowes, “The Bear Dresser’s Secret”

Paul Bowles, “The Circular Valley”

Mikhail Bulgakov, “The Sinister Apartment” (Ukraine), translated by Ekaterina Sedia

Italo Calvino, “The Origins of the Birds” (Italy), translated by William Weaver

Leonora Carrington, “A Mexican Fairy Tale” (UK/Mexico)

Angela Carter, “Alice in Prague or The Curious Room”

Angela Carter, “The Erl-King”

Stepan Chapman, “State Secrets of Aphasia”

Fred Chappell, “Linnaeus Forgets”

C.J. Cherryh, “The Dreamstone”

Alberto Chimal, “Mogo” (Mexico), translated by Lawrence Schimel

Alberto Chimal, “Table with Ocean” (Mexico), translated by Lawrence Schimel

Julio Cortázar, “Cronopios and Famas” (Argentina), translated by Paul Blackburn

Samuel R. Delany, “The Tale of Dragons and Dreamers”

Manuela Draeger, “The Arrest of the Great Mimille” (France), translated by Brian Evenson and Valerie Mariana

David Drake, “The Fool”

Rikki Ducornet, “The Neurosis of Containment”

Henry Dumas, “Ark of Bones”

Carol Emshwiller, “Moon Songs”

Musharraf Ali Farooqi, “The Jinn Darazgosh: A Qissa” (Pakistan)

Rosario Ferré, “The Youngest Doll” (Puerto Rico), translated by Rosario Ferré and Diana Vélez

Jeffrey Ford, “The Weight of Words”

Karen Joy Fowler, “Wild Boys: Variations on a Theme”

Sara Gallardo, “The Great Night of the Trains” (Argentina), translated by Jessica Sequiera

Alasdair Gray, “Five Letters From an Eastern Empire”

Elizabeth Hand, “The Boy in the Tree”

M. John Harrison, “The Luck in the Head”

Zenna Henderson, “The Anything Box”

Marie Hermanson, “The Mole King” (Sweden), translated by Charlie Haldén

Joe Hill, Pop Art

Nalo Hopkinson, “Tan-Tan and Dry Bone” (Canada)

Rhys Hughes, “The Darktree Wheel”

Intizar Husain, “Kaaya-Kalp (or Metamorphosis)” (Pakistan), translated by C. M. Naim

Shelley Jackson, “Foetus”

Tove Jansson, “The Last Dragon in the World” (Finland), translated by Thomas Warburton

Diana Wynne Jones, “Warlock at the Wheel”

Vilma Kadlečková, “Longing for Blood” (Czech Republic), translated by Martin Klima and Bruce Sterling

Bilge Karasu, “The Prey” (Turkey), translated by Aron Aji

Caitlín R. Kiernan, “La Peau Verte”

Stephen King, “Mrs Todd’s Shortcut”

Marta Kisiel, “For Life” (Poland), translated by Kate Webster

Leena Krohn, “The Bystander” (Finland), translated by Hildi Hawkins

R.A. Lafferty, “Narrow Valley”

Victor LaValle, “I Left My Heart in Skaftafell”

Tanith Lee, “Where Does the Town Go At Night”

Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas”

Fritz Leiber, “Lean Times in Lankhmar”

D.F. Lewis, “A Brief Visit to Bonnyville”

Kelly Link, “Travels with the Snow Queen”

Rochita Loenen-Ruiz, “The Wordeaters” (Philippines/Netherlands)

Gabriel García Márquez, “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” (Colombia), translated by Gregory Rabassa

George R.R. Martin, “The Ice Dragon”

Patricia McKillip, “The Fellowship of the Dragon”

Edgar Mittelholzer, “Poolwana’s Orchid” (Guyana)

Michael Moorcock, “The Dreaming City”

Haruki Murakami, “TV People” (Japan), translated by Alfred Birnbaum

Pat Murphy, “On the Dark Side of the Station Where the Train Never Stops”

Vladimir Nabokov, “Signs and Symbols” (Russia)

Garth Nix, “Beyond the Sea Gate of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe” (Australia)

Silvina Ocampo, “The Topless Tower” (Argentina), translated by James and Marian Womack

Ben Okri, “What the Tapster Saw” (Nigeria)

Victor Pelevin, “The Life and Adventures of Shed XII” (Russia), Translated by Andrew Bromfield

Rachel Pollack, “The Girl Who Went to the Rich Neighborhood”

Sumanth Prabhaker, “A Hard Truth About Waste Management”

Terry Pratchett, “Troll Bridge”

Qitongren, “The Spring of Dongke Temple” (China), Translated by Liu Jue

Maurice Richardson, “Ten Rounds with Grandfather Clock”

Joanna Russ, “The Barbarian”

Edgardo Sanabria Santaliz, “After the Hurricane” (Puerto Rico), translated by Beth Baugh

Ramsey Shehadeh, “Creature”

Leslie Marmon Silko, “One Time” (poem)

Han Song, “All the Water in the World” (China), translated by Anna Holmwood

Margaret St. Clair, “The Man Who Sold Rope to the Gnoles”

Avrom Sutzkever, “The Gopherwood Box” (Belarus), translated by Zackary Sholem Berger

Antonio Tabucchi, “The Flying Creatures of Fra Angelico” (Italy), translated by Tim Parks

Sheree Renée Thomas, “The Grassdreaming Tree”

Karin Tidbeck, “Aunts” (Sweden), translated by the author

Tatiana Tolstaya, “The Window” (Russia), translated by Anya Migdal

Amos Tutuola, excerpt from “My Life in the Bush of Ghosts” (Nigeria)

Jack Vance, “Liane the Wayfarer”

Satu Waltari, “The Monster” (Finland), translated by David Hackston

Sylvia Townsend Warner, “Winged Creatures”

Manly Wade Wellman, “O Ugly Bird”

Jane Yolen, “Sister Light, Sister Dark”

__________________________________

The Big Book of Modern Fantasy, edited by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, is available from Vintage.

Jeff and Ann VanderMeer

Ann VanderMeer currently serves as an acquiring editor for Tor.com and Weird Fiction Review and is the editor-in-residence for Shared Worlds. She was the editor-in-chief for Weird Tales for five years, work for which she won a Hugo Award. She also has won a World Fantasy Award and a British Fantasy Award for coediting The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories.

Jeff VanderMeer is the New York Times bestselling author of the Southern Reach trilogy, the first novel of which, Annihilation, won the Shirley Jackson Award and was made into a film by Paramount Pictures. His recent novel Borne has been selected for the NEA Big Reads program and was a finalist for the Arthur C. Clarke Award.