On the Archetypes of the Captivity Narrative

Aimee Parkison on Our Ongoing Literary Fixation with Trapped Women

When girls and women are held captive in literature, who is the archetypal girl in the story chamber? And why is she confined? What crime did she commit to deserve captivity?

You’ve seen her before: the girl too beautiful for her own good, a woman enslaved by her role in society, the daughter who dares to defy the mother, a woman who breaks the unwritten rules of motherhood, the woman who dares to insult a powerful paternal male, the sister who terrifies, the prisoner threatened if she communicates the wrong things to the outside world, the women hidden inside the wall of the very house where she lives, a murder victim, a girl like an object prized by a collector, a young woman who is merely trapped inside her body. Or merely a woman who did the wrong thing by standing up to someone in power and rejecting a stereotypically passive feminine role.

Whichever type of transgressor she may be, she’s a powerful archetype.

Most of her crimes have to do with the condition of being female, a condition that motivates “collectors” who are captors of girls. These captors are of various types—the lustful, the violent, the authoritarian, the disciplinarian, the doctor, the abductor, the warden, the brother, the husband, the parent, or the lover. Even you, as a reader, must become like her captor by getting closer to her to examine her fully, to understand her, but something holds you back—the very chamber that confines her, the story chamber, also builds walls around her so that you can only come so close.

The story chamber works in fascinating ways to display her. The very narrative walls that hold her captive allow you to look at her, as long as you want and as many times as you like, through the act of reading, but never to actually face her.

If we admit she’s an endless source of fascination, perhaps we should be compelled to ask why. Why keep revisiting her kind? What is so satisfying about her narratives, and what does it mean about society? Certain readers might be afraid to become her while others only want to behold her. Which type of reader are you?

“The Fall of The House of Usher” by Edgar Allan Poe

In Gothic tradition, an unnamed narrator goes to visit his curiously afflicted friend from childhood, Roderick Usher. Roderick is depressed from the recent loss of this twin sister, Madeline, who is buried inside the family mansion. The narrator and Roderick are horrified to discover Madeline has been confined in her resting place.

“The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

A woman accused of being mad is slowly driven insane by a confinement cure. Imprisoned by her physician husband in a room with yellow wallpaper, she loses touch with reality as the wallpaper opens onto another world that threatens her sanity while offering escape.

Choke Box: A Fem-Noir by Christina Milletti

The truth is hidden in the counter-memoir of Jane, a ghost writer confined in the Buffalo Psychiatric Institute. Like “The Yellow Wallpaper,” Choke Box calls into question misogynistic practices used to treat women where “treatment” is confinement.

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Under a new social order of a dystopian future, young women called Handmaids must allow their bodies to become hosts to the unborn children of powerful males.

Beloved by Toni Morrison

Sethe, born into slavery, escapes, but in attempting to free her children, she imprisons herself in a ghostly story chamber, a reminder of the horrors of slavery in American history.

The Collector by John Fowles

In this classic tale of kidnapping and misguided love, a man attempts to imprison the girl of his obsession like a butterfly under glass, but her captivity does not go as planned.

Various Men Who Knew Us as Girls by Cris Mazza

This ambitious novel reveals a spectrum of sexual captivity in contemporary times from sexual harassment to sexual slavery, where smuggled contraband is teenage girls.

Frances Johnson by Stacey Levine

Weirdly funny, subtly disturbing, this unconventional comedy of manners tackles confinement in the life of a woman-girl trapped by society’s notions of female conformity. If Frances seems afraid for no reason, her fear is softly insidious.

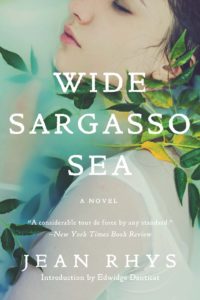

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys

A horror story of race, gender, and class, this reimagining of the madwoman in the attic (of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre) takes place well before the events of Jane Eyre. More than just the backstory of Mr. Rochester’s first wife, the novel tells the story of who she was before she became the madwoman. By the novel’s end, the reader understands she is not a madwoman but a sane woman driven out of her mind.

Aimee Parkison

Aimee Parkison’s collection of stories about girls in confinement, Girl Zoo, was published by FC2 and co-authored by Carol Guess. Her other books of fiction are Refrigerated Music for a Gleaming Woman, Woman with Dark Horses, The Innocent Party, and The Petals of Your Eyes. She teaches in the creative writing program at Oklahoma State University. More information about Parkison and her writing can be found at www.aimeeparkison.com