On Sylvia Plath’s Creative Breakthrough at the Yaddo Artists’ Colony

Good Things Happen When Writers Can Escape the World's Demands

After ten months of living in Boston, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes spent the fall of 1959 at Yaddo before returning to England. Plath was pregnant with her first child, and eager to spend three months writing without interruption in a room of her own. She had recently been a student in Robert Lowell’s creative writing class at Boston University, where she had befriended Anne Sexton.

Both had encouraged her to move in a looser, more autobiographical aesthetic direction. At Yaddo, she would break out of what she called her “glass caul,” confronting taboo subjects like paternal grief, suicide, institutionalization, and depression in bold cadences.

On September 9th, 1959, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes arrived at Yaddo, America’s preeminent artists’ colony, set on 400 pine-filled acres in Saratoga Springs, New York. Since the colony’s founding in 1900, a stint at Yaddo had become a rite of passage for American artists, many of whom had gone on to win Pulitzer and MacArthur prizes.

Sylvia and Ted would stay until November 19th. “They were very fond of each other, very quiet, kept much to themselves. Pleasant, hard working and appreciative of the kind of life Yaddo offered them,” the poet Pauline Hanson, Yaddo’s resident secretary, remembered.

Yaddo’s director, Elizabeth Ames, had heard about Plath from Alfred Kazin, who had written to her in 1955, “The best writer at Smith, and a very remarkable girl in every way, is Sylvia Plath, she is the real thing.” Four years later, Sylvia and Ted moved into a large first-floor bedroom, Room 1, at West House, the wood-and-stucco guest house just a short walk from the main mansion. Its grandeur impressed Sylvia: “The libraries and living rooms and music rooms are like those in a castle, all old plush, curios, leather bindings, oil paintings on the walls, dark woodwork, carvings on all the furniture. Very quiet and sumptuous.”

Each day after breakfast, the couple parted: Sylvia to her sunny third-floor studio, Room 8, in West House; Ted to his small, one-room cottage, “Outlook,” in the woods. From nine to four, Sylvia sat at her “huge heavy dark-wooded table,” typing on her new Swiss-made light green Hermes 3000 typewriter, before four east-facing windows overlooking the “tall dense green pines.”

Yaddo’s monasticism allowed Plath to focus on her art. “The only sound is the birds, and, at night, the distant dreamlike calling of the announcer at the Saratoga racetrack,” she wrote home. “I have never in my life felt so peaceful and as if I can read and think and write for about 7 hours a day.” Hughes, too, relished the solitude as he worked on his play The House of Taurus, a modern version of Euripides’ The Bacchae.

A five-minute walk separated the couple during their working hours, but it was enough to make Sylvia feel a new independence. “I am so happy we can work apart, for that is what we’ve really needed,” she admitted to her mother Aurelia and brother Warren. Though Sylvia would later complain that Yaddo was too monastic—like a “nunnery”—this was the first time in her life she was completely free of both academic and domestic obligations.

Even during her previous stretches of uninterrupted writing time in Spain, Boston, and Cape Cod, she had been responsible for the cooking, shopping, cleaning, dishes, laundry, ironing, mending, typing, bookkeeping, and the myriad other tasks that fell to women in the 1950s. At Yaddo, she was able to separate from Hughes, literally and figuratively. Her new pregnancy, her freedom from domestic chores, and her private studio helped her inhabit a less circumscribed psychological space that enabled her to make daring creative leaps.

At one point Sylvia became frustrated. “I don’t know what we’re doing here,” she said.There were only 12 other artists at Yaddo that fall, and the grounds were quiet. Sylvia and Ted walked the winding, wooded trails through the estate, and lingered in the European-inspired rose garden. Each morning Ted woke early to fish; he caught bass in the small lake but threw them back since the estate’s food was so fine.

Sylvia was still trying to learn German, “painstakingly” studying the language for two hours a day. The outside world intruded only by mail—rejections and acceptances, and letters from Aurelia full of anxiety about her heavy teaching load at Boston University.

Sylvia, Ted, and the young painter Howard Rogovin formed a trio. Howard became especially close to Ted. The two men often fished together on Yaddo’s lakes, and walked down to the Saratoga racetrack to watch the horses. In the evenings, the three artists retreated to West House’s ornate sitting room, a luxurious retreat with a grand fireplace, immense Persian rug, stained-glass windows, art deco lamps, and grand portraits. There, they sometimes listened to music with the composer Gordon Binkerd.

One evening, Howard remembered, Sylvia read her poem about a Bruegel painting, “Two Views of a Cadaver Room,” which she had written the previous summer, out loud to them. Ted sometimes drew astrology charts of great writers and Yaddo guests. But the three of them—and sometimes Pauline Hanson, Yaddo’s secretary—spent most of their time sitting at the Ouija board. Ted was the ringleader; Sylvia seemed less excited but went along. Howard was sure that Ted cheated—his answers were too interesting.

Ted convinced Howard to paint portraits of himself and Sylvia. She was reluctant, but Ted finally persuaded her. She sat for three or four sessions of about 40 minutes each, dressed conservatively in a sweater and wool skirt. Ted recited poems and read D. H. Lawrence aloud while Howard painted in the style of contemporary German painters Max Beckmann, Lovis Corinth, and Ernst Kirchner. At one point Sylvia became frustrated. “I don’t know what we’re doing here,” she said. “Why do it?”

Howard joked that one of them might become famous. Plath was a talented visual artist and had painted self-portraits. But she did not like ceding control of her image and instinctively recoiled before the male gaze. Hughes later wrote the poem “Portraits” about the sessions, published in Birthday Letters. According to Howard, Ted added several ominous details, like the dark human figure in the painting’s background, which he interpreted as Sylvia’s “demon.”

“He thought I sensed her instability, but I was just swirling some paint around,” Howard said. Nor did Howard remember the appearance of a snake, which Hughes turned into a dark symbol in his poem. “There was no snake. That’s Ted.”

Plath wrote a short story, “The Fifty-Ninth Bear,” during her first week at Yaddo but felt only “disgust” for the “stiff artificial piece.” (It would be published in The London Magazine in 1961.) She spent hours in the Yaddo library reading The Sewanee Review, the Kenyon Review, The Paris Review, The Nation, Art News, and The New Republic. She made a point to read female writers such as May Swenson (a Yaddo guest that fall), Katherine Anne Porter, Jean Stafford, Iris Murdoch, and Eudora Welty, as well as Robert Lowell, Theodore Roethke, Paul Radin, Freud and Jung.

She finally sat down with Elizabeth Bishop’s poetry, and was impressed by her “fine originality, always surprising, never rigid, flowing, juicier than Marianne Moore.” All of it made her wonder when she herself would “break into a new line of poetry” that was not “trite.” She criticized herself for her inability to get outside her own subjectivity: “Always myself, myself,” as she put it.

Her creative anxiety subsided on September 30th after she began a story titled “The Mummy,” a “mother story,” since lost, that she called “a simple account of symbolic and horrid fantasies.” She finished it on October 4th and was amazed at how her language dovetailed with passages she had read in Jung’s The Development of Personality, which she found in the Yaddo library.

Plath read Jung’s book, full of mother blame, at a crucial point in her poetic development. She was already attuned to Jung through Hughes and her psychiatrist Dr. Beuscher, who considered herself a Jungian analyst. Now it was as if Jung had read her mind: “Mother,” he wrote, “projected all her phobias onto the child and surrounded her with so much anxious care that she was never free from tension.”

Neuroses in children were “more symptoms of the mental condition of the parents than a genuine illness of the child.” And so on. Jung gave Plath permission, as her psychiatrist Dr. Beuscher had, to blame her mother for her mental maladies. This idea was entirely in keeping with the psychiatric biases of the day. Such permission seemed to release something in Plath, who was herself on the brink of becoming a mother and alarmed by Jung’s statement that “neurotic states are often passed on from generation to generation.” She dreamed that her own mother was “furious with my pregnancy, mockingly bringing out a huge wraparound skirt to illustrate my grossness.”

It was a moral imperative, Jung wrote, to honor the “Promethean” and “Luciferian” aspects of her own personality.The Development of Personality also contained a lengthy disquisition on “fidelity to the law of one’s own being.” Those who achieved “greatness,” Jung wrote, have “never lain in their abject submission to convention, but, on the contrary, in their deliverance from convention.”

Jung’s ideas resonated with Plath, who had refused a comfortable life as a doctor’s wife against her mother’s wishes and her culture’s expectations. It was a moral imperative, Jung wrote, to honor the “Promethean” and “Luciferian” aspects of her own personality. His ideas dovetailed with those of Robert Lowell and Anne Sexton, whom Plath had met earlier that year, and Hughes; all sought to break with convention in their work and their lives.

These influences coalesced at Yaddo, where Plath, uninterrupted—finally—with a room of her own, found courage in “walking naked,” as Yeats once wrote. Soon she began to confront, rather than sidestep, her psychic pain in her poems.

October was largely a month of rejections. Sylvia wept when Henry Holt turned down her poetry manuscript, but she sent it to Viking the next day, and then to Farrar, Straus on October 30th. Ted offered her some radical advice: “start a new book.” She was determined to do so, but the rejection sent her back into a black state.

Even The New Yorker acceptance of “A Winter’s Tale” on October 7th could not rouse her. Knopf rejected her children’s book The It-Doesn’t-Matter Suit, about a group of Germanic brothers loosely based on her father’s family. She seemed to hit a new low in mid-October:

Very depressed today. Unable to write a thing. Menacing gods. I feel outcast on a cold star, unable to feel anything but an awful helpless numbness. … Caught between the hope and promise of my work—the one or two stories that seem to catch something, the one or two poems that build little colored islands of words—and the hopeless gap between that promise, and the real world of other peoples [sic] poems and stories and novels. My shaping spirit of imagination is far from me.

Ted—still “the ideal, the one possible person”—practiced deep-breathing and stream-of-consciousness “concentration” exercises with Sylvia in mid-October, and she was able to write two poems that “pleased” her: “The Manor Garden,” about her unborn child (whom she called Nicholas during her pregnancy), and “The Colossus,” on “the old father-worship subject.” These, along with “Medallion,” about a dead snake, would comprise the beginning of her new book.

“The Manor Garden” is a dark twist on Yeats’s beneficent “A Prayer for My Daughter.” Plath hopes to bestow a blessing, but she cannot deny the forces that threaten her baby: “You inherit white heather, a bee’s wing, // Two suicides, the family wolves, / Hours of blankness.” “The Colossus,” too, subverts traditional expectations. It is an angry yet tender paternal elegy—a freer, less reverent revision of her earlier “Electra on Azalea Path.”

The surrealist poem envisions a daughter-caretaker who tends to her father’s immense statue on a deserted island. Plath incorporates elements of The Tempest, Robinson Crusoe, and Gulliver’s to create a proto-feminist elegy. This was the poem that the poetry critic Helen Vendler—who had joined Plath for stroller walks as an infant—would later declare Plath’s first real poetic triumph. Plath jettisons decorum with a vengeance:

I shall never get you put together entirely,

Pieced, glued, and properly jointed.

Mule-bray, pig-grunt and bawdy cackles

Proceed from your great lips.

It’s worse than a barnyard.

Perhaps you consider yourself an oracle,

Mouthpiece of the dead, or of some god or other.

Thirty years now I have labored

To dredge the silt from your throat.

I am none the wiser.

Here Plath mocks patriarchal tradition, which she cannot or will not master: the father’s language sounds like a series of grunts. “The Colossus” and “The Manor Garden” offer neither comfort nor blessing to dead father and unborn child. They are the antithesis of the sentimental feminine homily. Finally, Plath was fulfilling her Jungian destiny, as she wrote in her journal at Yaddo that November, “To be true to my own weirdnesses.”These subversive, ironic poems helped free Plath to confront the taboo of her breakdown and suicide.

Sylvia enjoyed sketching the Yaddo greenhouse, a short walk down the hill from her studio. On October 22nd, she mulled over an idea during a walk with Ted: “dwelling on madhouse, nature: meanings of tools, greenhouses, florist shops, tunnels, vivid and disjointed. An adventure. Never over. Developing. Rebirth. Despair.”

Ted wrote his sister Olwyn from Yaddo, “Sylvia has suddenly begun to write in a completely new style—obviously her own at last.”The next day they brainstormed on a single piece of paper. Several themes that found their way into Plath’s “Poem for a Birthday” sequence appear in Hughes’s handwriting: “Witch-burning,” “Change of vision of a maenad, as she goes under the fury,” “The stones of the city,” “Person walking through enormous dark house,” and “Flute notes from a reedy pond.”

Plath noted the ideas she liked in a small square in the right-hand corner: “Maenad,” “The Beast,” “Flute notes from reedy pond,” “stones of city—the city where men are mended MOULTS,” “witch burning.”These would all become titles in the sequence that Plath called “a series of madhouse poems.”

On October 23rd, Plath wrote that the poetic exercise she had tried the day before, which had begun in “grimness,” had turned “into a fine, new thing.” Between October 22nd and November 3rd, she used the Yaddo greenhouse and tool shed to conjure the mental hospital in spare, arresting language:

This shed’s fusty as a mummy’s stomach:

Old tools, handles and rusty tusks.

I am at home here among the dead heads.

Let me sit in a flowerpot,

The spiders won’t notice.

My heart is a stopped geranium.

In the sequence’s final, strongest section, “The Stones”—written in a form that gestures to Dantean terza rima—Plath faces her experience less obliquely. Using the same Swiftian, surrealist imagery she had discovered while writing “The Colossus” only a few days before, she describes the mental hospital as factory and assembly line: “This is the city where men are mended. / I lie on a great anvil.”

A workman walks by carrying a pink torso.

The storerooms are full of hearts.

This is the city of spare parts.

[…]

Ten fingers shape a bowl for shadows.

My mendings itch. There is nothing to do.

I shall be as good as new.

As in the end of The Bell Jar, the final declaration of recovery is ironic and ambiguous: we are not at all sure the speaker is cured. Indeed, the surrealist fantasy and the explicit “weirdness” of the sequence suggest that perhaps she is not.

“Poem for a Birthday,” “The Manor Garden,” and “The Colossus” show that children, fathers, and doctors are not to be idolized in Plath’s new poetic universe. These revolutionary new poems were a personal cri de coeur along the lines of Lowell and Sexton, but buttressed—as Hughes later noted—by surrealism, history, and myth. Ted wrote his sister Olwyn from Yaddo, “Sylvia has suddenly begun to write in a completely new style—obviously her own at last.”

The irony is that the style was borrowed from Theodore Roethke’s “The Lost Son.” Hughes later wrote that “the sequence began as a deliberate Roethke pastiche,” yet Plath knew this new note was also hers.“ The absence of a tightly reasoned and rhythmed logic bothers me. Yet frees me,” she wrote in her journal.

After Plath’s death, Hughes would write that in “The Stones” he heard, for the first time, the “real” or “reborn” voice of her deep self. He later remembered, “Bowed over your desk at Yaddo / Moored in some psychic umbilicus / Writing your Poem for a Birthday. / You thought it was your birthday, / Your rebirth. You wanted to be reborn.”

As if confirming her new aesthetic direction, James Michie, a young half-Scottish, half-American editor at the British publisher Heinemann, contacted Plath that October expressing admiration for the poems she had recently published in The London Magazine (“In Midas’ Country” and “The Thin People”), where he was a member of the editorial board. He asked her to send him her poetry manuscript; a year later, Heinemann would publish The Colossus, the only collection of her poetry Plath ever saw in print.

By November there were only six guests left at Yaddo, all living in West House—Plath, Hughes, Howard Rogovin, May Swenson, Gordon Binkerd, and Arthur Deshaies. Plath wrote “The Burnt-Out Spa” on November 11th, and, two days later, “Mushrooms.” But by mid-November her adrenaline subsided, and she wrote nothing new during her last week. “Paralysis again,” she wrote in her journal. “How I waste my days. I feel a terrific blocking and chilling go through me like anesthesia.”

“My tempo is British,” Plath wrote, and, indeed, British editors seemed more amenable to her dark wit.She wondered if she would “ever be rid of Johnny Panic.” She had barely achieved anything, she felt, in the past ten years. She was convinced that she had written no good story since “Sunday at the Mintons” and felt that she needed more space from Ted. “Dangerous to be so close to Ted day in day out,” she wrote in her journal on November 7th. “I have no life separate from his, am likely to become a mere accessory.” They must “Lead separate lives.” She did not “dare open Yeats, Eliot.”

As the end of their Yaddo stay approached, Plath began to feel an “Odd elation,” which she attributed to their upcoming departure for England. John Lehmann had accepted her short story “The Daughters of Blossom Street” for The London Magazine, news that made her skip through the grounds like a child. She was particularly pleased by this acceptance, as the magazine’s editorial board included Elizabeth Bowen.

Lehmann himself had helped Virginia and Leonard Woolf run the Hogarth Press. Plath was cheered, too, by the publication of “A Winter’s Tale” in the December 12th New Yorker. She hoped the three stories and eleven poems she had written at Yaddo would help make her name in England.

“My tempo is British,” Plath wrote, and, indeed, British editors seemed more amenable to her dark wit. She thought that in England she would be less afflicted by her “commercial American superego.”She despaired of “breaking” the “drawingroom [sic] inhibitions” in her prose, but in her poems, she knew, “There I have.”

Still plagued by nightmares of dead babies and “puritannical” [sic] mothers, she mustered her old optimism. “Whenever we are about to move, this stirring and excitement comes, as if the old environment would keep the sludge and inertia of the self, and the bare new self slip shining into a better life.”

She was moving to England to find this new life—a “pioneer / In the wrong direction,” Hughes later wrote—but her desire for reinvention was American.From now on she would live, she wrote, in a “blithe, itchy eager state where the poem itself, the story itself is supreme.”

__________________________________

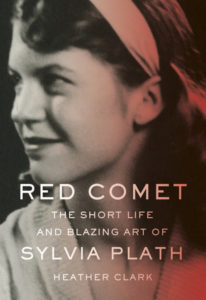

Excerpted from Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark. Copyright © 2020 by Heather Clark. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.