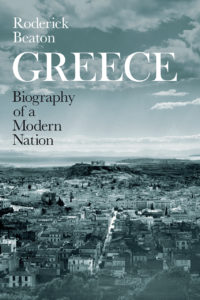

On Rethinking the 'Modern' in Modern Greece

From Roderick Beaton Greece's Cundill-Prize Nominated Greece: Biography of a Modern Nation

The story I have set out to tell in this book is the story of Greece as a modern nation. I have chosen, therefore, to understand the term in its narrower, more rigorous sense, and so to begin the narrative with the century that led up to that nation’s birth.

Another choice has been to imagine this modern nation as though it were a living person, the subject of a biography. The life of a nation and the lives of individuals present fascinating, perhaps even illuminating, analogies—notably the ideas that bind a nation together are more often than not themselves based on organic metaphors. Let us then suspend disbelief and concede—hypothetically, experimentally—that the Greek nation ‘born’ out of revolution in the 1820s shares some of the characteristics of a human subject. We can trace the history of that subject just as a biography teases out the life and career of an individual.

A nation, just like an individual, has distant ancestors and a more immediately traceable genealogy, or family tree. In the life of nations, Greece, born in this sense in the early nineteenth century, must be considered still a youngster. And there is one characteristic of biography, as a genre, that in this case we can happily escape. A nation in the fulness of time may evolve into something else, but there is no reason to expect the story to end in death. All will surely agree on this in the case of Greece. No obituary is to be expected. The biographer is spared the dubious benefit of looking back on a life complete and ended. Think of this book, in this respect at least, as more like a “celebrity” biography that leaves its subject still in the prime of life and fame. The story does not end with the end of the book.

But first, we need to begin at the beginning, with ancestors, and the complex inheritance that issues from them.

*

None of us knows who our most distant ancestors were. If all modern humans are descended from groups that began to migrate out of Africa more than fifty thousand years ago, then the Greeks must be no exception. Future advances in genetics may reveal to what extent those who speak the Greek language today share genetic material with the builders of the “classical” civilization of antiquity. In terms of understanding the history of the Greeks in modern times, it really doesn’t matter. History on the scale of a few millennia is shaped by such things as environment, actions, events and ideas, not evolutionary biology. What is at stake here is not the literal, biological ancestry of the individuals who make up a population—even if those are the terms in which it is most often expressed—but rather the “ancestry,” in a partly metaphorical sense, of a nation, a state, or that complex phenomenon that we call a culture. It is doubtful whether ancient Greek civilization can properly be called a nation, and it certainly was never a state. Nevertheless, Greeks experience a sense of kinship with those they call “our ancient ancestors.” The phrase has become something of a cliché in recent decades, and is widely acknowledged as such. Even so, it sums up a great deal of what continues to define the Greek nation in the modern world.

A nation, just like an individual, has distant ancestors and a more immediately traceable genealogy, or family tree.

This sense of kinship was articulated in its most nuanced form by the poet George Seferis, in his speech accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1963: “I do not say that we are of the same blood [as the ancient Greeks]—because I have a horror of racial theories—but we still live in the same country and we see the same mountains ending in the sea.” Seferis also laid stress on the continuity of language: the words for “light of the sun,” he pointed out, are almost unchanged from the equivalent words used by Homer almost three thousand years ago. Like most of his generation, Seferis had experienced the horrors unleashed upon the world by the racist dogma of the Nazis in the 1930s and 1940s. It is an affinity that he asserts, based upon landscape and the language in which humans have engaged with it over time—an affinity deeply felt, but not a dogma, and not built upon genetic assumptions.

____________________________________

Greece: Biography of a Modern Nation by Roderick Beaton has been shortlisted for the 2020 Cundill History Prize.

____________________________________

It is not only Greeks who share this perception. How often in the years following the financial crisis that began in 2010 have the cartoonists of the world’s media drawn upon classical stereotypes and images in order to give visual expression to the sorry state of a once-great civilization? Images of ancient temples with their gleaming marble riven with cracks, of a euro coin as a badly thrown discus causing havoc, have gained a place in the popular imagination in countries far removed from Greece, often with an edge that is critical, if not downright hostile. Among Greeks themselves, it is the same sense of affinity that lends such passion to calls for the return of the “Elgin Marbles,” or Sculptures of the Parthenon, removed from the Acropolis of Athens by Lord Elgin in the first years of the nineteenth century and since 1817 exhibited in the British Museum in London. These creations by craftsmen of extraordinary skill and imagination who have been dead for two and a half millennia have come to be imagined in their turn, in the memorable words of the film star and popular singer, and later Minister of Culture, Melina Mercouri, as “our pride . . . our aspirations and our name . . . the essence of Greekness.”

This is not something that can be denied, or simply wished away. Some have argued that the gene pool of the ancient Greeks cannot possibly have survived successive migrations and invasions over the centuries. Others dismiss an obsession with ancestors as ways of avoiding the facts of history. But this is to miss the point. We are talking about a sense of kinship, a perception, not a set of facts that can be objectively verified. The sense of affinity with the ancients is itself a historical fact, to be understood and explained. How it came to exist at all, and then to exercise such an enduring hold, is an essential part of the story of how Greece became modern, which is the story of this book.

*

So used are we, today, to thinking of “modern Greece” as an offshoot of ancient Greece, it can be hard to realize that for many of the centuries separating classical antiquity from ourselves no such sense of affinity existed among Greek speakers. The people we call “ancient Greek” did not call themselves that. The names “Greek” and “Greece” derive from Latin: Graecus and Graecia. It was the Romans, as they conquered most of “Graecia” in the second century BCE, who made these names famous. Ancient Greeks called themselves “Hellenes”—the word is almost identical in English and Greek. The lands where Hellenes lived were collectively called Hellas. The same names, in their modern form, are standard in Greek today: the people are Ellines (with the stress on the first syllable), the country is either Ellas (the older form) or Ellada. So what has changed?

The answer is: a great deal. By the 4th century CE, those populations of the eastern Mediterranean hinterlands that spoke and wrote in Greek had been living for hundreds of years under the rule of Rome. When Christianity was adopted as the official religion of the Roman Empire during that century, the use of the term “Hellene” in Greek came to be reserved for those Greeks who had died too soon to benefit from the new religion, and could therefore not help being pagans. Before long, and by extension, “Hellene” came to mean just “pagan,” that is, anyone who was not a Christian. Throughout the Christian Middle Ages, that remained the primary meaning of the word in Greek. With the spread of secular ideas in the eighteenth century, “Hellene” became predominantly an antiquarian term: the “Hellenes” were the ancient Greeks, whereas living speakers of the Greek language had centuries ago found a different name for themselves. It was a conscious choice, taken during the first National Assembly of the Provisional Greek Government in January 1822, to revive the ancient names: “Hellenes” for the citizens of the new state that was then fighting for its independence, “Hellas” for the state itself.

Names, too—place names and personal names—often seem to imply a closer kinship than historically exists.

In the same way, the drachma, to which it is often supposed that Greece would return if the country were to leave the Eurozone, is often called “the world’s oldest currency.” The name is as old as you could wish for—but for approximately seventeen centuries before its re-introduction in 1833, not a single drachma had ever been minted. To take another example, Athens in antiquity had fought its way to pre-eminence among the rival Greek city states; the ruined classical temples on the Acropolis at its centre have for long been iconically synonymous with Greece itself. It is an easy assumption to suppose that Athens has always been the capital city. In fact, it became the capital for the first time on December 13, 1834.

Names, too—place names and personal names—often seem to imply a closer kinship than historically exists. Look at any map of Greece, and at least half the names of towns and geographical features can also be found in ancient sources. But many of these were deliberately revived, after independence, to replace the customary names that had been in use for centuries, and which still appear on older maps and in travellers’ accounts. On the Gulf of Corinth, for instance, the hard-to-pronounce “Aigio” has replaced “Vostitsa” that Lord Byron visited and where a famous conclave of revolutionary leaders took place in 1821. “Troezene,” the birthplace of Theseus in mythology, returned in the 1820s to oust the long-familiar “Damala,” where a medieval French barony had once had its seat. Old names have been replaced by ancient ones, replacing one history with another. Or take personal names. For a millennium and a half all children of Greek Orthodox parents had been baptized with the names of saints in the Church calendar. It was not until the 1790s that these names came to be paired, or replaced altogether, with the names of famous pagans from antiquity. A Greek today can be called Odysseus or Socrates or Euclid, Penelope or Calliope, and one might suppose these names had run in families ever since ancient times. Not so. This is something else about ancestors: you can pick and choose.

To acknowledge these facts is not, of course, to diminish the immense significance that these ancestors have come to assume in defining Greek collective identity over the last two centuries. Only when you realize the full extent of the choices made by hundreds and thousands of Greeks during those years does the scale of the achievement become apparent. It was a conscious and, it would seem, a little-contested policy choice, beginning around 1800, to reassert kinship with the lost civilization of classical antiquity. It has also been a highly selective one. Think of all those ancient practices that have been entirely airbrushed out: nudity, pederasty, slavery, submission of women, infanticide, paganism, animal sacrifice.

And as a policy, it has been overwhelmingly successful—as those cartoons of discus-euros and cracked marble columns sadly testify all too well.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Greece: Biography of a Modern Nation by Roderick Beaton. Used with permission of University of Chicago Press. Copyright 2019 by Roderick Beaton.

Roderick Beaton

Roderick Beaton is Emeritus Koraes Professor of Modern Greek and Byzantine History, Language and Literature at King’s College London and Commander of the Order of Honour of the Hellenic Republic. He is the author or editor of multiple books, including Byron’s War: Romantic Rebellion, Greek Revolution.