On Rendering My Own Novel Into Spanish

Carolina De Robertis: "Spanish is the language of my bones."

When people ask me which is my mother tongue, English or Spanish, I usually respond that when it comes to language I have two mothers. Just like my own children, I add.

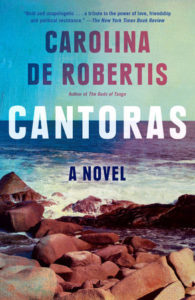

The idea that we can only have one mother is a narrowing assumption, both in our familial and linguistic lives. And yet, it’s also true that our relationships to our mothers—and our mother tongues—can be infinitely complex, nuanced, primal, and ever-changing. This why, when I was invited to translate my own novel Cantoras into Spanish, I knew immediately that the task would be transformative, in ways I couldn’t yet fathom.

I have spent most of my life yearning for more intimacy with the language of my country of origin, Uruguay. I was primarily educated in English; it is the language of my intellect, the one in which I can best vault and flow along the curves of syntax as I reach for meaning. The era of my adolescence and early adulthood that I spent swallowing hundreds of novels—which, unbeknownst to me then, helped make me a writer—all happened in California, and in English.

That said, though English dominates my intellect, Spanish is the language of my bones.

And if I am to be entirely accurate, let me say that it’s not simply Spanish that’s my bone-language, my marrow-language, but ríoplatense Spanish. There is no word for “ríoplatense” in English. Not only that: in a nation where Spanish is treated as a low-status language, where television news can refer to “three Mexican countries” while supposedly reporting on Central America, where the infinitely rich complexities of Latinx immigrant cultures are dismissed and flattened into condescending tropes—well, in such a nation, of course the dazzling overlapping linguistic constellations of the Spanish-speaking world would go unseen. (Which, if you know a thing about the magnificence of cubano or mexicano or colombiano or dominicano or hondureño or guatemalteco or any other regional Spanish, is a loss beyond measure.)

Many of us who are heritage speakers have internalized the idea that our bonds with our mother tongues are lacking, that any flaws mean they are less ours.

Ríoplatense is a word that means “of the Río de la Plata region,” i.e., from Argentina and Uruguay. Our Spanish is weird, slanted, full of idiosyncrasies and its own insistent melodic twists. Always, every second, I experience it with a hunger and longing and deep love, for I grew up as an immigrant in three different countries, hearing ríoplatense Spanish only in my own home, as if it were my family’s private language rather than a broader public one.

The first time I was ever surrounded by strangers speaking ríoplatense Spanish, I was 16 years old. I was at an airport gate, alone, about to board a flight to South America, where I’d be meeting relatives for the first time. It flooded me from all sides. Conversations rose, crested, overlapped like waves. A ríoplatense sea, composed of music, words, the word-music of home. A rushing in my ears. I was shaken to tears. In fact, even now, I still can’t talk about that night without my eyes stinging. There was a level of belonging that I hadn’t known was possible, in which your whole linguistic self could reverberate in the world, could weave into the world and return to you. After that trip, I existed in a new way.

Since that night at the airport, I have often swum through the question it opened: how much belonging is possible for me? It is a question that has driven my most significant life choices, as well as the writing of all my novels—though of course that for me has become a for us, with the us shifting like beads in a slow kaleidoscope to spill into larger stories of who we are in this world, and what it means to affirm our lives as they really are in a world that seems bent on our erasure.

Many of us who are heritage speakers have internalized the idea that our bonds with our mother tongues are lacking, that any flaws mean they are less ours. But what if we could explode that notion? What if we could shift the narrative toward one that holds us unconditionally, exactly as we are, affirming the ways our mother tongues belong to us and we to them?

*

I knew translating Cantoras would be transformative, but I also knew it would be extremely hard. The vast majority of literary translators work in one direction, bringing text into their dominant or stronger language, and, in my career as a translator, my primary direction has been Spanish to English. I first became a translator by falling into it, passionately, obsessively, staying up too late for the sheer exhilaration of swimming the space between languages in the name of art. I’d since translated six novels from Latin America and Spain, as well as shorter works, including some for which I reversed directions, but an English-to-Spanish rendering of this scope and complexity was a new challenge for me.

And yet, I knew I had to say yes. For one thing, I wanted to ensure that the novel landed, not just in strong Spanish, but in a genuinely ríoplatense Spanish, and I knew from experience that it didn’t always go that way. When my first novel, The Invisible Mountain, was translated in Madrid, I read the manuscript and was alarmed to find it brimming with the word “coger,” which in Spain means to get or take or pick up or grab, but in ríoplatense Spanish very decidedly means to fuck, which had not been my intention for those characters with that bus, or flower, or book, or friend’s hand. (Granted, that might have made for an interesting book, but that’s another story.) After a long fight, I was able to get the style changed for the Uruguayan and Argentinean edition, but for Cantoras I wanted to steer clear of such risks altogether.

Another reason had to do with the book itself. Cantoras follows five lesbians in Uruguay through the dictatorship years of the 1970s and 80s, and beyond, as they draw on their friendships for love and survival. The story is inspired by real women who shared their stories with me over the course of 18 years, women whose stories healed me and helped me find a place for myself in the world when I was young, searching, and trying to piece together a sense of self as a queer woman in the Uruguayan diaspora. Also, extensive research had shown me that the stories of LGBTQ+ folks in that era of Uruguayan history were completely undocumented, shrouded in silence. I felt a great responsibility to do justice to their stories in a culturally authentic voice.

But there was a catch: I didn’t quite have the chops to pull it off on my own. My love of ríoplatense Spanish runs endlessly deep, but love and technical capacity are not the same thing. Love for gymnastics won’t keep you from falling off the high beam. It pains me to admit it, but there is a higher level of syntactical and lexical limberness that is out of reach for me beyond English. A good translator doesn’t have to know everything, but she does need to be able to see her limits and address them. I sought the support of a brilliant friend, Marcelo de León, who kindly agreed to consult on the project. And with that, I dove in.

Changing the direction of translation’s flow, from Spanish to English, is like changing the direction of a river as it flows through the same bed. Everything changes.

It was as hard as I thought it would be. Harder, in fact. But it was also joyful. Translation is a literary art form in which one draws on already extant material to forge a voice that might, in the words of Edith Grossman, create a “parallel aesthetic experience” to the original. I thought it might be difficult to resist the temptation to edit myself, to rewrite the book rather than express the same text in a new language, but it was not. It was even a relief. No invention, now: just language, in its raw power, rhythmic and human and pure. At times, it felt exhilarating to ride the sentences, to feel the truth of them pulsing awake in a new voice. At other times, the pleasure of hearing these characters not only speak to each other, but think in ríoplatense language—to call a thing chiquito rather than pequeño, to say acá rather than aquí, to move from voseo to tuteo as reflected by the nuance of the moment—would choke me up with emotion, a profound kind of arrival home.

Changing the direction of translation’s flow, from Spanish to English, is like changing the direction of a river as it flows through the same bed. Everything changes. You see the topography anew. I found myself grieving the gaps in my ríoplatense Spanish skills, while also deepening my intimacy with this beloved mother tongue, for intimacy is a story with no ending as long as we’re alive. I also found new layers of love for English: its rich colloquialisms, its distillations, the syntactical shapes it can create with gerunds, hinging thoughts together, spurring connections, as I just did in those last two clauses. That same construction, in Spanish, does not go well. There came a point I thought I’d die from lack of gerunds, of –ing verbs. Spoiler: I did not die. Instead, on returning to English, I inhabited its unique constructions with new gratitude, even as I pined for the reflexive verbs whose superpowers Spanish had been unfurling to me.

In the end, thanks to Marcelo’s hard work and my own, I emerged with a manuscript I could stand behind, one that welcomes Spanish-language readers of any background, but that I could also send to my tías and primos and the dear friends whose lives inspired this book and say, not aquí lo tienes, but, a lo ríoplatense, acá lo tenés. I can put all my ferocious love and thanks into those three words. Here you go / you have it / it’s yours.

As I was translating Cantoras, I booked a flight to Uruguay with my wife and kids, our first trip back together in six years and a long-held dream. The flight was for July 2020. Instead of taking that trip, we sheltered in place as the coronavirus pandemic raged all around us. We don’t know when we’ll be able to fly home, to our other home: everything is uncertain. I know that I’m among the lucky and the privileged; many of my undocumented counterparts share my longing to visit their homelands but have long been unable to do so. I have papers that my undocumented friends do not, but they have just as much right to be here as I do. As I ache to visit the country that is my other home, I am one among millions, and I remember with sorrow that the pain of others is greater than mine.

I want to go home. Many of us want to go home. Many of us wonder what home even means. The world is often brutal, alienating. It can be an exhausting battle to simply be seen, or safe. Whether as an immigrant, as a lesbian, or as a Latina, I refuse to wait for the world to catch up to us in order to be whole. If we are to flourish, if we’re to take triumphant root in the world, perhaps we might find it useful to rewrite our understanding of home. Perhaps we might look inward, too. No matter where we are, or what we find ourselves facing, we carry our languages deep within us. We are our languages, for language does not exist without people; it comes alive on human tongues, in human souls. We have, in our bones, the makings of our own belonging. Our mother tongues are already perfect inside us, beautiful and sufficient, beckoning us home.

__________________________________

Cantoras by Carolina De Robertis is available via Vintage.

Carolina De Robertis

Carolina De Robertis, a writer of Uruguayan origins, is the author of The Gods of Tango, Perla, and the international best seller The Invisible Mountain. Her novels have been translated into seventeen languages and have garnered a Stonewall Book Award, Italy’s Rhegium Julii Prize, and numerous other honors. A recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, she is also a translator of Latin American and Spanish literature, and editor of the anthology Radical Hope: Letters of Love and Dissent in Dangerous Times. In 2017, the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts named De Robertis to its 100 List of “people, organizations, and movements that are shaping the future of culture.” She teaches at San Francisco State University and lives in Oakland, California, with her wife and two children. www.carolinaderobertis.com