Louis Armstrong’s Rapturous First Tour Through the American South

Ricky Riccardi on the Musician's Enthusiastic Reception in New Orleans

About to embark on a southern tour for the first time, Louis Armstrong was leaving behind the comfort of the police escort that kept him safe in Chicago. He needed a bodyguard and decided to hire a friend from his past, drummer “Little” Joe Lindsey. Armstrong was once the cornetist in Lindsey’s Brown Skin Jazz Band, one of his first professional experiences as a musician. He also invited his down-on-his-luck New Orleans friend—and “one of the all-around gamblers of that period”—“Professor” Sherman Cook to be his valet and serve as something of a personal secretary. New Orleans was his eventual destination and it would help to have two homeboys to keep him safe in the south.

Kentucky was the first stop for what was billed as “Louis Armstrong of Screen, Stage and Record Fame and His Okeh Recording Orchestra”; multiple advertisements played up Armstrong’s appearance in Ex-Flame, further proof of the importance of this film at this point in his career. They played a dance date on May 15th at the Club Madrid, the night before the Kentucky Derby, and followed that with a “Kentucky Derby Ball” in Louisville.

“We were the first colored band ever to play that, and that was some engagement,” saxophonist George James recalled. Collins had to take gigs wherever he could find them, which meant following the Kentucky sojourn by traveling back up north to Detroit to play opposite McKinney’s Cotton Pickers at the Graystone Ballroom and Jean Goldkette’s Orchestra at the Blue Lantern.

Armstrong’s reed-heavy band cooked on stage, and in guitarist Mike McKendrick they had a good “straw boss” to discipline the members and make sure they were always ready when they needed to be. Bassist John Lindsay of New Orleans (no relation to Joe) joined in Detroit, a solid addition who locked in with drummer Tubby Hall to form a potent rhythm team. But what the band really needed was a music director and in Detroit, they found one in trumpeter Zilner T. Randolph.

Randolph was born in Durham, Arkansas, on January 28th, 1899, and like many musicians of his generation, fell under the spell of Armstrong after hearing him in the 1920s, saying to himself, “That’s the kind of horn I want to play, I want to play that.” When Armstrong returned from California, Lil Armstrong began studying arranging with Randolph, which put him on Louis’s radar.

One time at the Regal, Randolph went backstage with a song he had written, “I Don’t Care What You Do,” and showed it to Armstrong. Randolph said, “I didn’t know too much about Louie and everybody had told me that Louie couldn’t read music.” Armstrong took one look at it, started scatting the melody and “took me off my feet,” according to Randolph. “He was singing all those intervals.” Randolph went back and told his wife, “They say Louie can’t read music. Louie took that song and solfèged that song off. He solfèged that song off direct from sight.”

The police helped guide Armstrong through the crowd of thousands of people—including five bands—but many in the crowd did not emerge unscathed.Though Lindsay and Randolph were regulars in Chicago, they didn’t join Armstrong until opening night at the Graystone. Armstrong must have been impressed because after the first intermission, he said to Randolph, “Hey Randy, pick you out a set and take it down. Now, this is your band.” This caught the rest of the band off guard. “When he said that, why, they all looked at one another,” Randolph said. “But I didn’t think nothing of it, you know.”

Though some of the other members resented the immediate promotion for the new man, Armstrong was satisfied. With Randolph handling the music, McKendrick handling the band business, and Collins doing the booking, Armstrong was free to just concentrate on his trumpet playing and singing and not worry about anything else. He would later refer to this as his “happiest” group, writing of them, “Now there’s a Band that really deserved a whole lot of credit that they didn’t get.”

Armstrong started for New Orleans, playing one-nighters in Minneapolis, Ohio (including a college date at Ohio University), and another swing through Kentucky, again, all territories Collins used to book in his vaudeville days. Professor Sherman Cook had already left Armstrong to head to New Orleans—by taxicab—to begin working on a grand reception for the trumpeter’s arrival. Armstrong had not been back at all since July 1922 and might not have expected much of a welcome, but Cook’s handiwork promised a “monster reception” and a “gigantic parade.” It was not hyperbole.

The Armstrong band traveled to New Orleans by private rail car, arriving on Friday, June 5th. “When we arrived at the station there, Cook had spreaded the news, and the L & N station out by the Canal Street Ferry were packed and jammed with people who I was raised with, played with, and lots of spectators waiting for our train to come in,” Armstrong wrote. “We took Canal Street for ourselves, stopped all the traffic; all the cops gave us the right of way when they found out it was their home town boy Louis ‘Satch’ Armstrong, returning home after nine years.”

The police helped guide Armstrong through the crowd of thousands of people—including five bands—but many in the crowd did not emerge unscathed. The parade ended at the Astoria Hotel, where Armstrong and his band were guests of honor at a special banquet. The huge crowd gathered outside the hotel to get a glimpse of the conquering hero, but soon grew restless.

“Arguments ensued and then fights, and complaints began pouring into the First Precinct police station,” reported the New Orleans Times Picayune. “Captain George Reed and seven patrolmen responded, and when the street was finally cleared about midnight 29 negroes had been booked on charges of loitering, disturbing the peace and numerous other minor offenses.”

While that was happening outside the Astoria Hotel, Armstrong was being honored inside, sharing his table with Captain Joseph Jones and Peter Davis, the two men who were the most vital in changing his life at the Colored Waif ’s Home in 1913. Because they had an exclusive contract with the Suburban Gardens, Armstrong’s band didn’t perform at the Astoria but when he sensed the crowd’s disappointment, he offered a vocal version of “The Peanut Vendor.” But it soon appeared that might be the only song he’d perform in his hometown: Armstrong and his band had been expelled from the National Federation Union of Musicians.

__________________________________

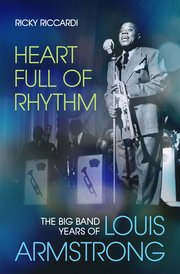

From Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong by Ricky Riccardi. Copyright © 2020 by Ricky Riccardi and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.