On Racial Injustice and the False Promise of Police Reforms

Derecka Purnell Unpacks the Drive to Seek Justice

Police reforms are such tyrannical prizes. Winning them feels relieving, never satisfying. Poet Nayyirah Waheed writes that “desire is the kind of thing that eats you and leaves you starving.” Each indictment that a cop faced increased my craving for justice, and each non-indictment made me feel that due season would come one day.

Many activists who demanded “Justice for Trayvon Martin” carried the same demand into the movement against police violence. In 2013, the #BlackLivesMatter website listed several demands to “end injustice in our community”: federal charges against George Zimmerman, no new jails, prisons, or immigration detention centers, and the re-opening of the cases of all people whose lives had been stolen by law enforcement, security guards, and vigilantes. The following year, the website’s creators, Patrisse Cullors, Opal Tometi, and Alicia Garza, were adding to the calls to arrest Darren Wilson as “justice for Michael Brown,” and petitioning Attorney General Eric Holder to “release all names of all officers involved in killing black people within the last five years so they can be brought to justice.”

Though its meaning had been elusive in high school, I was coming around to the idea that justice—for Michael Brown, Rekia Boyd, and Walter Scott among others—clearly meant what we were chanting in the streets: “Indict! Convict! Send that killer cop to jail! The whole damn system is guilty as hell!”

We wanted to win. Cops expected to win, too, and the odds were in their favor. Many wore “I Am Darren Wilson” bracelets around St. Louis. In November 2014, I sat on my gray carpet in the big blue house and cried when a grand jury returned a bill of no-indictment for the killing of Michael Brown. A grand jury also chose not to indict two cops who killed John Crawford, a Black man who was holding an unloaded air rifle while on the phone inside a Walmart; nor Daniel Pantaleo, the cop who placed Eric Garner in a fatal chokehold for selling loose, untaxed cigarettes on Staten Island. Bystander Ramsey Orta captured the encounter and released the footage showing Garner buckling and repeating “I can’t breathe!” NYPD officers wore black t-shirts with white writing that read “I Can Breathe.” Mayors, governors, and the president asked us to remain calm and trust the system, the same system whose cops mocked the people they gunned down.

Massive protests swept the country for each person, first for their death, then for the deaths of their cases. I hoped that all of our hard work, from the streets to the campuses, would pay off. I thought it had, briefly, in the first half of 2015. New York Police Department officer Peter Liang was indicted for killing Akai Gurley. On February 10, 2015, Liang had killed Gurley, a Black man, in the dark hallway of the Brooklyn projects. Liang opened a door and fired his weapon. A bullet ricocheted and hit Gurley who was coming up the stairs with his girlfriend. Liang’s indictment was the first of many high-profile killings since the Ferguson Uprising began. But, unlike the white cops who evaded charges, Liang is Chinese American.

We need “firsts” to do more than break the barriers to get into the system; we need them to break the system itself.

Many Chinese Americans and immigrants varied in their reactions to the indictment. Some demanded his prosecution and joined multi-racial protests that had signs with “Black Lives Matter” written in Chinese. Others conveyed that the indictment was racist and that he was a scapegoat for all of the other cops who walked free. In a double-plot twist, Judge Danny Chun convicted Liang and sentenced him to probation and community service. Akai was killed, and there would be no jail time. I think about this when people ask me of abolition, “What about the killers?”

Liang’s case demonstrated the limits of calling for cop convictions and the limits of diversity. Having more people of color in a corrupt system did not mean that they would be interested in changing it. Liang is Asian. He was prosecuted by Ken Thompson, the first Black District Attorney in Brooklyn. Liang was sentenced by Judge Chun, the first Korean American prosecutor and first Korean American judge in New York City. In 2019, Judge Chun did not sentence two NYPD cops, including one Black one, who had “sex” in a police van with a teenager in custody. Rather, the judge defended his decision by saying that the victim and the cops were involved in criminal activity, and that the victim could also be charged and found guilty for offering a bribe.

Later that year, the judge sentenced a Black former NYPD cop to probation for shooting a man in the face and then planting a knife next to the body. If the criminal legal system only had white judges, prosecutors, and cops, then we could more easily assume the presence of racism or white supremacy. But with diversity, people of color can make the legal system appear more neutral or just by the virtue of them being “firsts.” We need “firsts” to do more than break the barriers to get into the system; we need them to break the system itself.

I had not fully come to these conclusions about diversity by the time of the news of Freddie Gray’s death. Two weeks after Walter Scott’s death, Baltimore cops made eye contact with Freddie Gray. Gray, like Walter, ran. Nobody knows why. The official police report stated that Gray “fled unprovoked,” as if police do not regularly cause harm to poor Black men like him, and as if recent viral videos of police shooting and strangling Black men to death did not provide enough provocation for them to flee. Cops chased and caught him, patted him down, and discovered a small switchblade. They dragged his folded body to a cage inside of a van. For 45 minutes, they drove through the city on a “rough ride,” a law enforcement tactic of driving harshly to physically punish arrestees who run. In the process, those cops severed Gray’s spine. He died days later on April 19, 2015.

Kevin Moore recorded the police dragging Gray and once he released the footage, Black people poured into the streets. Policymakers tout body cameras as a major reform in the wake of police violence, but civilian cop watch is much more powerful and democratic. When we stop to record police encounters, our presence can sometimes discourage further violence from cops. If we record cops who continue to escalate violence and get it on camera, then we are in control of the footage; this differs from body and dashboard camera footage because cops can turn them off or misconstrue the angle. Cities also withhold footage of cop shootings until a family, journalist, or lawyer sues or protests for access. At risk to themselves, the brave civilians who record cops informally on the streets or formally in community Copwatch programs could literally save lives and expose additional police terror. I would learn more about the shortcomings of body cameras after the protests.

Many activists and lawyers went to Baltimore to support the protesters who faced police in riot gear, just as they descended upon Ferguson. Justin Hansford, my friend from St. Louis, was there providing legal support, too. After a few conversations with him about the need for more legal observers, I decided to go. Harvard’s BLSA paid for me and three of my closest friends from law school, Mmiri Mbah, Christina Joseph, and Titilayo Rasaki, to drive from Cambridge to Baltimore to protest and provide legal support to activists.

I woke up the next morning ready to go and quickly learned horrible news. My former classmate, Korie Hodges, had been killed in cold blood and possibly in front of her children. Her friend, Keerica Bolden, was also discovered dead right beside her. Korie’s father found them. The headline was so horrible that I called the news station and fought with them to change it: “Accused Ferguson Looter Found Dead Two Days After Being Charged.” They kept it. Despite the fact that her death had nothing to do with the charges that she was facing, the news was eager to rely on the sensationalism of Ferguson and looting to attract readers to their site. Friends from my high school wanted justice for Korie. I did, too.

They wanted to know why people protested police violence but didn’t protest violence in our own Black neighborhoods. I thought about the elder from the community meeting in Kansas City years before. I think he was warning us that many of the underlying causes of community-based violence and police violence were rooted in the same oppressive systems but required different kinds of solutions if we were going to stop the violence. These facts do not bring anyone’s baby back from the dead. But we can use them to create better solutions in our communities to save more lives. I wished Korie’s father could have found her oversleeping because her alarm failed to ring, instead of finding her lifeless.

Between Korie and Freddie Gray, the drive down was deeply emotional for me. I found solace in being with my friends, reuniting with Justin, and meeting new activists in the streets. During the day, cops mounted horses, drove cars, and raided buildings in response to the protests. In Ferguson, the bulk of the protests happened on two major streets, West Florissant and North Florissant.

But Baltimore’s occupation was significantly larger and spread throughout the city. Titilayo, Christina, Mmiri, and I joined lawyers, law students, and legal workers in the National Lawyers Guild and a formation that became the Black Movement Law Project to monitor police. Several organizations trained us for cop watch, legal observation, bail, and jail support.

We connected with other law students from Howard University and Catholic University of America, and lawyers who attended the National Lawyers Guild legal observer training at the University of Maryland. I was shocked by the power and command of Black law students who organized the support networks behind the scenes, especially Marques Banks. Marques became part of the Black Movement Law Project. He was a bubbly, detail-oriented strategist and trainer during the uprising in Baltimore. When we worked together later in Ferguson, activists would run away from the police when they escalated violence. Marques was one of the few people who would run toward the fires to help others. Because of courageous people like Marques, I stopped praying to be fearless and started praying to be relentless, so that even when I am afraid, I try to move to closer to freedom.

__________________________________

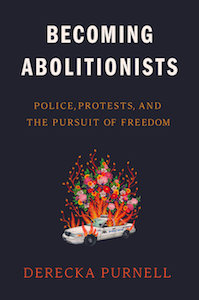

Excerpted from Becoming Abolitionists: Police, Protests, and the Pursuit of Freedom by Derecka Purnell, with permission of Astra House, publishing October 5, 2021. Copyright © 2021 by Derecka Purnell. All rights reserved.

Derecka Purnell

Derecka Purnell is a human rights lawyer, writer, and organizer. She received her JD from Harvard Law School, and works to end police and prison violence by providing legal assistance, research, and training to community-based organizations through an abolitionist framework.