On Navigating the Intricacies of Race and the Violence of Antiblackness in America

Nadia Owusu Reflects on Her Years in America as a Young Adult

New York, New York, Age 28

There is something black children, especially black girls, are told from a very young age. You know what it is. It has made its way into the political discourse and into television sitcoms. Statisticians have worked to prove and disprove it. Young black people talk about it at happy hours and black student association meetings. We say it silently with nods to one another when we meet in places we are not expected to be: as we take our seats on a panel of experts, for example. Or when we check in with the receptionist at a job interview for a VP position at a big corporation. Our eyes say it when they meet the eyes of other black people at glitzy charity balls. We say it to ourselves as we get dressed and step out into a world that was designed to fail us, to see us fail. You have to work twice as hard to get half as far.

It is platitude and truism. It is ubiquitous. It is a persistent whisper in our ears. It is the graffiti carved into the bathroom door.

My father was the first person to say it to me. I was four and had complained about being made to work on my letters and numbers all afternoon instead of being allowed to play outside like the neighbors’ (white) children. My father was unsympathetic. After that, he would shake his head and say twice as hard, half as far anytime I brought home a less than perfect report card or was given a less than glowing assessment at a parent-teacher conference.

I have heard the phrase repeated by black people in Africa and in America. My Jamaican friend said it when she got passed over for a promotion she felt she deserved. Her eyes were wet. She blamed herself for leaving the office before ten at night “for a month when I had walking pneumonia.” My Ethiopian friend said it when I pushed him to skip studying for his bar exam for one night—his birthday—so I could take him dancing. He shrugged his shoulders when he said it, rolled his eyes.

Michelle Obama said it in a 2015 speech at Tuskegee University. She reminded the mostly African-American graduating class that they would be scrutinized harder. They would see their successes attributed to others or dismissed altogether. They would be judged more harshly for their failures.

Black people are expected by the white world to be strong but not angry. Pain must be hidden. Daily slights are to be borne with grace, humility, even gratitude. Weakness is intolerable. Vulnerability must wait until the day is done and the mask can come off in the privacy of our own homes. And by then we might be too tired or too stiff to feel it. This is not just true for black people living in Europe or America. It is also true, in a different form, in Africa and the Caribbean, where black people are the majority. People in former European colonies must see their lives in relation to the lives of white people. As communities, as individuals, we have been told we are inferior. Our economies, our livelihoods, are reliant on Western economies, white people’s livelihoods.

Black people are expected by the white world to be strong but not angry. Pain must be hidden. Daily slights are to be borne with grace, humility, even gratitude.

As my seismometer vibrated, as the alarm wailed, I did not stop trying to be twice as good. I would not have known how to stop. We become the stories we are told.

“You are small, black, and female,” my father said to me once, near the end, when he was full of warnings. “People will try to cut you down to size. They will think you are weak. They will try to tell you who you are. Never give them the opportunity to think they’re right.” It was you have to work twice as hard, rephrased.

A few weeks before retreating into the blue chair, I was on the third of a triple shift at a restaurant. I also had a part-time job at a nonprofit. A triple shift meant that I worked a night shift, got home at two in the morning, then went back to the restaurant to work from ten in the morning till after midnight. My rent was due in a week and I was still one-third short. I could not afford to give up shifts. It was also finals week. When I got home from the triple shift at one in the morning, I made a pot of coffee and started studying for the next day’s statistics exam. I studied and cried. I usually cried when I studied for quantitative tests because I’m very bad at math. Doing things I’m very bad at makes me sad about all the things in the world I will probably never really understand, like electricity and Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

But this was worse than my typical response to math. I was terrified I would not get an A. Maintaining a 4.0 GPA in graduate school was of the utmost importance. I believed that if I got anything lower than an A on anything, my life would fall apart. I did not, at the time, believe this in an abstract sense. As night turned into day, my crying became more and more hysterical. I was getting problems wrong. Getting problems wrong meant getting life wrong. I worked on one problem for three horrendous hours. Sometime after sunrise, I passed out with my cheek pressed into my textbook. I dreamt of being summoned to an office where I encountered a panel of tall white men who told me I had failed. In the dream, I begged and they laughed and laughed. Even as I begged, I smiled at them.

I woke up with a jolt. I had to be at my nonprofit job in one hour. My exam was that evening. At the office, my boss asked how I was doing.

“Great!” I exclaimed, my smile quivering at the corners. She did not notice.

Looking back on it now, my fear seems absurd. Not a single person, not even when I was interviewing for jobs, asked me what my GPA was. No one asked me about my grade on my statistics final. I got an A minus. To my traumatized brain, it might as well have been an F.

The point of graduate school was to get a full-time job that paid me enough so I wouldn’t also have to work at night. I just wanted a job that didn’t feel like a slow death. By this point, I had been rejected for more than forty jobs for which I had interviewed. Managers were always super-enthusiastic about me in phone interviews, but when I walked into rooms, they often looked startled. When they called to say I didn’t get the job, they sounded sheepish, almost apologetic. They told me how great I was and said they were certain I’d find something soon. In almost every instance, they cited culture fit as the reason why the job had gone to someone else. I blamed myself. There must be something wrong with me and how I was presenting. I started straightening my hair again and wearing makeup. Writing and rewriting cover letters and résumés became a compulsion. I didn’t have networks to speak of, or networking skills. My introversion makes me hopeless at events designed to help candidates meet employers, but I started going to them anyway which was not helping with my anxiety. I thought I just wasn’t smart enough or good enough. I had failed. I was a failure.

The point of graduate school was to get a full-time job that paid me enough so I wouldn’t also have to work at night. I just wanted a job that didn’t feel like a slow death.

The day after my statistics final, I went on yet another job interview, for an international nonprofit that helps refugees fleeing conflict and natural disasters, primarily in the “developing world.” The woman doing the interviewing was my age, preppy, white. Her name was something like Brittany or Tiffany. She had on a real pearl necklace and a big diamond engagement ring.

“You lived in Uganda?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “High school.”

“That’s great. We do some work there. Our CEO is there now, in Kigali.”

I didn’t tell her that Kigali is in Rwanda not Uganda.

“I work on our Africa program,” she continued.

I didn’t get the job. When Brittany-Tiffany emailed to let me down, she wished me the best and told me, just as a heads-up, “to be helpful,” that there was a typo in my résumé. She didn’t tell me what it was, and I was too embarrassed to ask.

“All of that is going to be a heavy burden to carry,” Michelle Obama said in her speech at Tuskegee University. “It can make you feel like your life somehow doesn’t matter.”

If your life doesn’t matter when you are working twice as hard and being twice as good, then it certainly won’t matter if you find yourself sitting on the floor in a puddle of your own piss like the woman I saw in the Ugandan hospital, or stripping off all your clothes at a cocktail party, or talking to imaginary people, or being forced into exile in a blue chair by a seismometer in your head. In Ghana, you might end up chained to a tree, covered in paint, waiting for Jesus to save you. In America, you might get shot by the police.

On October 29, 1984, a black woman named Eleanor Bumpurs was shot and killed by the NYPD. The police had been called to her apartment in the Bronx to enforce a city-ordered eviction. Bumpurs was four months behind on her monthly rent of $98.65.

The NYPD had been informed by the housing authority that Bumpurs was emotionally disturbed and that, to resist eviction, she had previously brandished a knife and threatened to throw boiling lye at officers. When Bumpurs refused to open the door, police broke in. In the struggle to subdue her, one officer shot her twice with a 12-gauge shotgun.

I knew about Eleanor Bumpurs because of Hurricane Katrina.

When the levees broke in New Orleans in 2005, I watched hours upon hours of footage of people stranded on rooftops and of people who had just lost everything suffering the indignity of being crowded into unsanitary and inhospitable tent cities in the Louisiana Superdome. “We pee on the floor. We are like animals,” said one woman to the New York Times. It was impossible not to notice that most of those people were black and poor. It was also impossible not to notice the language being used to describe them: looters, rioters, thugs. By comparison, I saw newspaper stories describing white people who waded through the water in search of food. They found bread, the journalists wrote. Found. Not stole. Not looted.

If your life doesn’t matter when you are working twice as hard and being twice as good, then it certainly won’t matter if you find yourself sitting on the floor in a puddle of your own piss like the woman I saw in the Ugandan hospital.

America was still a new land to me then and I was still trying to understand it. I was trying to understand what being black meant here, what it meant for me. I was trying to understand the ways in which I had become a different kind of black than I was in England, in Italy, in Tanzania, in Ethiopia, in Uganda, in Ghana. In each of those places, being black meant something different. My particular shade of black—light to medium brown with yellow or red undertones, depending on the season; middle-class; biracial—was valued differently in each of those places as well.

In the weeks after Katrina, I learned that, in America, being black and desperate in a disaster could lead to being labeled and treated like a criminal. I turned to Google to learn more about this. What I learned shocked me. What I learned was that black people had been shot, even killed, by the New Orleans police, for trying to survive.

The first of these documented incidents took place on September 1, 2005. Keenon McCann was shot multiple times by SWAT Team Commander Jeff Winn and Lieutenant Dwayne Scheuermann. The officers claimed McCann was armed, claimed he tried to ambush officers responding to a tip about a band of criminals who had stolen a truckload of bottled water. The criminals, the officers said, used the water to lure thirsty people only to rob them. McCann denied having a gun and sued the city. He was shot to death outside his home in 2008 before that case was tried. Winn and Scheuermann were not accused of a crime.

The day after McCann was shot, Henry Glover was killed by a rookie NOPD officer named David Warren outside a strip mall. Warren’s charge was to guard the mall from “looters.” To the NOPD, whatever was in the strip mall—packaged American cheese, Twinkies, soda, beer, maybe some deli meat, potato chips, I imagine—was more valuable than the lives of black people. Five officers, including Warren, were charged with trying to cover up Glover’s murder by setting fire to a car with his dead body in it. Warren was acquitted.

On September 4, nearly a week after the hurricane, several NOPD officers leapt out of a rental truck and fired their weapons at a group of black people crossing a bridge. Ronald and Lance Madison— brothers—were returning to a hotel where they were staying after being flooded out of their home. Also on the bridge were Leonard Bartholomew Sr., his wife Susan, son Leonard Jr., daughter Lesha, seventeen-year-old nephew James Brissette, and Brissette’s friend José Holmes. They had walked to a grocery store in search of food and supplies. Leonard was shot in the back, head, and foot. Susan’s arm was partially shot off and later had to be amputated. Lesha was shot four times. José was shot in the abdomen, hand, and jaw. James Brissette and forty-year-old Ronald Madison, who family say was mentally ill, were killed. An officer stomped on Madison before he died. None of the people on the bridge had committed any crime. The police fabricated a cover-up story. The officers, they claimed, were responding to a police dispatch report of an officer down. They claimed they were fired at. All lies, it was later discovered.

America was still a new land to me then and I was still trying to understand it. I was trying to understand what being black meant here, what it meant for me.

After reading those stories and many others, I wondered to what extent the post-Katrina murders were a heightened version of an everyday reality. I googled black people killed by police. Eleanor Bumpurs’s story came up, as did so many other stories of black women who died for the crime of mental illness.

In the years that followed Katrina, I continued to search for and to read with horror stories about police violence against black people, and particularly black women with mental illnesses. The searches became a strange routine. I visited ex-boyfriends’ Facebook profiles to see if they had found happiness without me, hunted for the perfect vintage high-waisted jeans, checked how many more black people had been shot and killed by police.

In 2009, Brenda Williams’s mother called the police in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and asked them to check on her daughter’s mental health. Her daughter, a fifty-two-year-old black mother and air force veteran, suffered from schizophrenia. This request for help ended with Brenda Williams being shot to death by police. According to the officers, she was naked and disorderly when they arrived. She went into the kitchen and charged out wielding a knife. Considering the officers knew her to be mentally unstable, this behavior should have been expected. Yet Williams was killed.

In my room, before becoming moored in the blue chair, I turned off all the lights and drew the blinds. I called the people who needed to be called in order to cancel my life, length of time unspecified. I was ill, I said, very ill. I was hospitalized. Then my phone and computer were banished to a drawer full of old keys and batteries. I did not trust myself to ask for help. I didn’t know if I could trust anyone to help me. Madness was coming, and no amount of working twice as hard could stop it now. My seismometer sputtered. It was spent, kaput. I had finally heeded the alarm. Now I was on my own. I would have to find my own way out. I hoped, despite my blackness, despite madness, despite the rules of race in America, I would make it out alive.

__________________________________

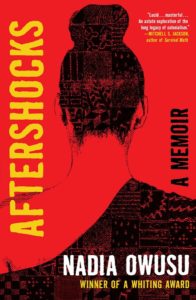

From Aftershocks: A Memoir by Nadia Owusu. Used with the permission of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by Nadia Owusu.

Nadia Owusu

Nadia Owusu is a Brooklyn-based writer and urban planner. She is the recipient of a 2019 Whiting Award. Her lyric essay, So Devilish a Fire, won the Atlas Review chapbook contest. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in the New York Times, the Washington Post's The Lily, Literary Review, and Electric Literature, among others. Aftershocks is her first book.