On Loving, Losing, and Returning to Poetry

Ari Honarvar Traces Her Relationship to Rumi, Her Mother, and Her Persian Identity

I was calling on a la la la status

thanks to disco number after the garage installed it is now.

Pissant!

A suitcase on made you down for dairy pro

so be there no child lyrics and

you crazy is it going to, maybe.Article continues after advertisement

This is an actual transcript of my speech to text app trying to decipher my mother leaving me a voicemail in Farsi. You see, my mother is a Persian poet lost in translation.

She and I come from Iran, the nation of poets and poetry lovers, where people recite poems not just at weddings, but to welcome sorrow, as answers to questions, and even to resolve conflicts. Children begin studying poetry in first grade and continue for much of their education. You hear poetry in conversations in remote villages and at trendy modern boutiques and offices. But for my mother, poetry is more than an art, a vocation, or a way to communicate—it’s like an extension of her five senses.

When I was little, we were shopping in a bustling bazaar when I got separated from her. Lost and scared, I walked on my tiptoes, trying to find her in a sea of giants. When my eyes filled with tears, it was her bright voice that drew me to the kiosk. She was reading a verse from an antique leather-bound Rumi:

Oh Pilgrims on your way to Hajj

Where are you going?

Your beloved is here!

Come back! Come back!Article continues after advertisement

As I stood next to her, I realized she hadn’t noticed my absence.

A few years later, during the Iran-Iraq War, I began to understand my mother’s reliance on poetry. One afternoon, when the threat of Scud missiles filled the airways with fear, we huddled around the radio in my parents’ bedroom as the program host invited the listeners to join his poetry contest. Challenging us to compose the second part of a rhymed verse, he recited the first hemistiche and, like a spell, his words banished all thoughts of war, food rations, and the dread of an imminent air raid.

For my mother, poetry is more than an art, a vocation, or a way to communicate—it’s like an extension of her five senses.

Every head in the room was filled with blooming possibilities of the perfect second line. Looking around, hoping to find my muse somewhere in the room, I caught our disrupted reflection in the large mirror on my mother’s vanity. The mirror was adorned by two pieces of tape in the shape of an X. This was meant to save us the post-attack cleanup, since blast waves shattered glass as easily as they shattered the sound barrier. In the mirror I saw my sister, her hair covering her eyes, hunched over writing furiously, my mother already sharing several second lines out loud, and my father’s furrowed brow as he turned his rosary beads. What but a poem could capture this moment that may have been our last?

As the war dragged on and the government oppression filled me with rage, I became a reckless teen. I wrote anti-regime graffiti on walls, a crime that could send me to jail or worse. In response, my mother wrote a poem about India’s Independence Day. She said a prayer and submitted it along with her visa application to India. The Indian ambassador must have liked the poem as he granted us a visa to India, where I could secure a meeting with the American embassy. America welcomed me, but the catch was that I had to come alone.

I landed in New Mexico and a kind American family took me in. But nothing could assuage the pain of separation. Being 14, without my motherland, my mother tongue, and my actual mother was like living in a Rumi poem. Like the cut reed, I was ripped from the beloved.

I stared out of the window into a vast suburban desert. I missed our lush garden, the scent of orange blossoms. I ate French fries alone at the school cafeteria. I tried not to think of our lazy summer lunches under the willow tree. I wanted to tell the world how I ached. I didn’t know English.

So I memorized 300 vocabulary words a day and watched Days of Our Lives religiously. I learned about the prevalence of death plots and evil twins in the American life. It was the farthest I had been from home, from poetry. By the second month, when someone asked me an innocuous question, channeling a soap opera diva, I retorted back: “What’s that supposed to mean?”

As I adapted to the American life, poetry became a blurry memory—a vestigial organ I had no use for. Teen years are long like dog years, full of exponential growth that shapes the person in a profound way. By the time my parents were able to move here, I had become a young woman with vastly different ideas and perspective from theirs. The new me in this new world couldn’t relate to them, and my mother, who hadn’t seen me in years, couldn’t understand the American version of me. It was as if I had turned into a foreign protein her body wasn’t able to digest. We fought a lot. And we had to find a way to live with each other as she often needed my help—like the day she asked me to place an ad to sell her car.

As I adapted to the American life, poetry became a blurry memory—a vestigial organ I had no use for.

We pulled into the parking lot of a strip mall that smelled of tacos and nail salon chemicals. We watched the buyer arrive, his face and demeanor vaguely resembling Steve Buscemi. As I discussed the car with the man, my mother, who had quickly lost interest in the conversation, stared at our reflection in the dark window of an office space. Then she began a passionate recitation in Farsi.

“Maman, not now,” I grumbled.

“I recited poems when I was in labor with you and when bombs were falling. Why can’t I do it when I’m selling a car?” Her impatient Farsi words fell like hail on the hot pavement. “He is a foreigner. He doesn’t understand what I’m saying.” She gestured wildly toward the man, who was getting more uncomfortable by the second.

I turned to the man. “I have the repair records right here.” I pointed to the folder in my hand.

By the time the man bought the car, I was utterly frustrated. Once again, my mother had made a simple affair difficult with her eccentricities.

“Come on! Let’s go,” I blurted and took off ahead of her but her voice stopped me cold in my tracks:

Oh Pilgrims on your way to Hajj

Where are you going?

Your beloved is here!

Come back! Come back!Article continues after advertisement

I turned around to see her pointing to a side alley.

“This is a better way home,” she yelled.

And for the first time I understood why she refuses to let go of her poetry. Why would anyone forgo the ineffable sense that always leads them to the exact place they need to be?

Now when a drunken word salad appears on my phone screen—“Have a youngest Cherry Coke for Amazon and yoga?”—I hear my mother’s resonant voice:

Where are you going?

Your beloved is here!

Come back! Come back!Article continues after advertisement

________________________________________________________

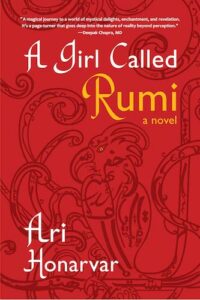

A Girl Called Rumi is available via Forest Avenue Press.

Ari Honarvar

Ari Honarvar is the founder of Rumi With A View, dedicated to building music and poetry bridges across war-torn and conflict-ridden borders. Her writing has appeared in The Guardian, Teen Vogue, Washington Post, and elsewhere. She is the author of the oracle card set and book, Rumi's Gift. She lives in San Diego, where she has befriended a hummingbird named Taadon.