On Horror, Heavy Metal, and Why We Love to Be Scared

Metallica Guitarist Kirk Hammett May be the World's Biggest Horror Fan

I was eight years old when I first encountered the movie poster for It’s Alive hanging in the lobby of the local mall theater. The poster’s central visual element—in fact, its only visual element—is a small wicker bassinet perched in the darkness. I knew there was something wrong with this image, but I didn’t realize what it was until I stepped closer: the only visible part of the baby is a long, pale, two-pronged claw that hangs over the edge of the basket and casts a fanged shadow.

There’s only ONE thing wrong with the Davis baby, reads the legend hovering over the bassinet. Beneath is a blood red kicker: IT’S ALIVE.

I realize, as I describe it, that this poster must sound incredibly cheesy, and perhaps somewhat absurd. But I can promise you that merely evoking this grim little manger scene in my mind, four decades later, is enough to prickle my skin with dread.

Here’s the craziest part: I never even saw It’s Alive. I was too scared to set foot in the theater. My older brother Dave eventually watched the film, which is about a mutant baby who literally emerges from the womb and starts killing people. It caused him to suffer nightmares for six months.

For all it did to terrify us, It’s Alive also played a vital catalytic role in the creative life of our family. Specifically, it transformed my brothers and me into horror auteurs. We spent several months making short films that dependably depleted our pantry’s supply of ketchup.

Our crowning achievement was titled Crispy Critters, in which a mad scientist cannibal boils innocent victims in a huge vat of hot oil and then devours them. Dave played the mad scientist cannibal. I played one of the victims. Our hot tub played the huge vat of hot oil.

There’s something profound to be learned here, beyond my poor choice in movie roles. It has to do with the intimate relationship between horror and creativity, the primal link that has always existed between the imaginative anarchy of the unconscious and the human impulse to make art.

*

As it should turn out, I wasn’t the only kid growing up in the Bay Area during the 1970s who obsessed over movie posters.

Just up the road from my suburban digs, in San Francisco’s Mission District, a kid named Kirk Hammett was immersing himself in the world of horror. The first film he ever saw, at the tender age of five, was called The Day of the Triffids. It was about man-eating plants.

That sounds pretty cheesy, too. But what matters here is the reaction the film evoked in Hammett. He was terrified. And he immediately began drawing the triffids that had terrified him. Horror begat art. That’s more or less the executive summary of his life.

Hammett spent his entire childhood chasing the high of horror, spending his lunch money on magazines such as Creepy and Famous Monsters of Filmland, camping out in front of Creature Features on KBHK Channel 44 (I was watching them, too), and surrounding himself with monster paraphernalia.

He did this because the world of the grotesque and macabre offered him a safe way of experiencing his own monstrous fears and desires. They plugged right into the roiling id of an alienated kid.

“It was difficult for me to relate to the world and cope,” he told me. “And to see these people on the screen who were also having trouble coping was reassuring, even though I wasn’t conscious of it at the time. I definitely related more to the monsters, the villains, the creatures, the mad doctors than I did to the heroes or the good guys.”

Horror wasn’t exactly therapeutic for Hammett, though. Its central function was to rev him up, not calm him down. Whenever he watched a movie or looked at a poster, he would be seized by intense feelings that instantly drove his creative impulses. The stuff of horror, as he put it, “has a mojo that always works on me. I start producing ideas. They just flow like liquid.”

The fevered emotions that horror inspired became the central engine of Hammett’s creative process. And the moment he picked up a guitar, those ideas came pouring out in a wash of notes.

*

One of the works I always think about in relation to horror is the painting Saturn by Goya. It’s not just the disturbing particulars of that canvas—the wide-eyed God clenching that decapitated body of his son in his fists—but the reminder that horror has haunted humankind for as long as we’ve been on the planet.

Francisco Goya, Saturn, 1819–23, mixed method on mural transferred to canvas, Museo del Prado.

Ancient mythologies are shot through with tales of monsters, mayhem, rape, bestiality, and incest—the full menu of taboos familiar to any fan of modern horror. The larger question is why human beings are drawn to these decidedly disturbing themes. What do we get out of them?

Aristotle was among the first to write about our attraction to horror, though he did so somewhat indirectly. His specific interest was in the effect of tragedy, which he insisted was to elicit feelings of pity and fear. More broadly, he felt that audiences were drawn to dramas that generated a restorative purging of the emotions, or catharsis.

“Horror returns us to the thrilling precinct of childhood by temporarily erasing the line between the imagined and real.”

Sigmund Freud, who was a neurologist in addition to being the father of psychoanalysis, addressed horror by introducing the concept of the uncanny, such as narrative elements that were both familiar and incongruous, and had the effect of simultaneously seducing and repulsing the audience. Like, say, a crib whose tiny occupant is both a baby and a monster.

Freud saw the uncanny as a pathway to our repressed impulses. By his reckoning, the reason my brothers and I were so freaked out by It’s Alive was that we unconsciously recognized that little mutant baby as a version of our own monstrous aggression. (Which, for the record, sounds pretty spot-on.)

Carl Jung used different terminology to arrive at the same conclusion. He insisted that horror films “tapped into primordial archetypes buried deep in our collective subconscious.” In particular, he saw horror as the realm of the shadow, the archetype that houses all our forbidden urges, from the murderous to the bestial.

My own theory—as the parent of three young children—is that horror returns us to the thrilling precinct of childhood by temporarily erasing the line between the imagined and real. We get to experience the rising tension of predation, the adrenaline spike of sudden violence, and the perverse pleasures of liberated gore. Our hearts start hammering, as they did when we were kids. We flinch and sweat and shriek. Then the lights go up and we march back into the respectable prison of our adult lives.

*

Of course, certain people find a way to avoid this fate. Kirk Hammett happens to be one of them.

Hammett was all of 21 when he flew from California to New York to audition for a band called Metallica. As a guitar prodigy with his own band, Hammett had already shared the stage with the guys from Metallica. But it wasn’t until he walked into that audition room that he recognized the ways in which horror had led him to heavy metal. Specifically, it was the sight of bassist Cliff Burton reading a Dungeons & Dragons handbook based on the short story The Call of Cthulhu by the renowned horror writer H.P. Lovecraft. “I pointed at that book and I said, ‘I have that, too! I love Lovecraft!’ This was literally the second day I was in the band.” Burton also carried a VHS copy of Dawn of the Dead with him at all times. Whenever the band had downtime, “we could pop that in and the party would start.”

But the connection was more profound than a shared aesthetic. “I could see that these guys were just as dark and messed up as I was,” Hammett said. “They had as much difficulty in coping as I did. It didn’t matter if Cliff and I were more drawn to movies than the other guys, we were all in that dark zone together. We all came from disenfranchised stock, and because of that we played our instruments a certain way. Our music was about confronting subjects that most people feel aren’t appropriate to confront, the stuff they’re afraid to confront.”

Which might as well serve as a working definition of horror.

*

It’s probably worth noting, at this point, that the final track on Metallica’s second album, Ride the Lightning, is titled “The Call of Ktulu.” It’s based on the Lovecraft story Hammett and Burton first bonded over and naturally features an extended solo by Hammett.

Fun fact: the reason the band chose to change the name from Cthulhu to Ktulu wasn’t just to make it easier to pronounce, but because in the Lovecraft story the very act of writing the name “Cthulhu” is said to invite the eponymous beast into your midst.

*

I’d known about Metallica for nearly a decade before I saw them live. And I’m embarrassed to admit that the reason I went to see them was because it was my job to do so. I was the music critic for the El Paso Times, and the band was headlining a triple bill at the County Coliseum.

Of course, I’d heard the band’s music before, screeching from various boom boxes and car radios. But I was the kind of angry young man who placed his faith in the bluesy mysticism of Van Morrison and the catchy angst of what was then called New Wave.

What I knew of heavy metal, as a genre, was predicated mostly on reviewing interchangeable glam bands such as Cinderella and Poison and Whitesnake. Their shows struck me as amped-up pop pageantry, with most of the emphasis on disposable riffs and the lead singer’s hair.

Which is to say: I was utterly unprepared for the Metallica experience. The arena faded to black and the crowd began to hoot and suddenly the air was smeared with sound: howling guitar, a drubbing baseline, percussive runs that I could feel rattling my teeth, and vocals that sounded like a demon sprung from the underworld.

I was horrified.

The sonic experience was so assaultive, so angry and chaotic. And yet, all around me were young men and women who knew every blurry note, every lashed beat, every growled syllable. They banged their heads in unison. They became a single swirling organism.

For the first 20 minutes or so, I tried to scribble down notes, like the young dutiful critic I was. But after a time, it just seemed pointless. There was no way to capture in words the spell the band cast. It was too visceral, too intuitive, a kind of violent exhilaration that I now recognize as the “feeling” Hammett kept mentioning when we spoke.

I’d brought my lawyer friend Will to the concert, another heavy metal newbie. Afterward, as we stumbled out into the warm desert night, I turned to him.

“What the hell was that?” I said.

“A horror movie,” he said.

*

I can’t remember a word of my ensuing review, thankfully. But I do remember that I listened to a lot of Metallica after that show, much to the consternation of my girlfriend. I’d get up in the middle of the night, slip a cassette tape into my Sony, and softly bang in the darkness.

My friend Will had been right, of course. The songs were horror movies: brooding and frenzied, awash in images of entrapment and predation. The song “Enter Sandman” struck me as especially emblematic of the band’s ethos. It was about a little boy who fears sleep because the terrors of his imagination will overtake him.

Years later, Hammett would explain the stubborn allure of horror to me this way: “It’s a very, very dark universe when we shut our eyes at night. My whole goal, when I play, is to take a listener into that darkness, to a place they’ve never been. And whether by route of angels or by route of devils, I’ll do anything to get the listener to that zone. That’s what all great art is about.”

Kirk Hammett performs with The Bride of Frankenstein poster guitar. Courtesy of Kirk Hammett.

*

If that sounds like a bummer agenda, please consider the following paradox: some human beings actually take joy in feeling scared. Not my daughter, though. Horror films make no sense to her at all. Why subject yourself to an experience designed to upset you?

But for those of us drawn to the dark arts, the goal is the one Aristotle envisioned: revitalization.

Horror allows human beings to contend with the two distinct burdens we face as a species. The first is that we’re acutely aware of our own mortality.

“We get to vicariously experience death and aggression, sadism and victimhood, from the safety of a darkened theater seat.”

In order to survive out on the Serengeti as a relatively weak prey species, we had to develop an acute and pervasive sense of fear. This fear proved useful. It spurred us to take measures to prevent being harmed or killed. We learned to build fires and fortresses. We learned to drill holes in gourds and fill them with rainwater, and to bury these gourds in the sand. The reason we went to all this trouble was because we were plagued by memories of our clan members—our children, our parents—being attacked by predators or rival clans, or dying of thirst during the long dry season.

The second burden we suffer is a highly developed moral code that operates in defiance of our basic aggressive and sexual impulses. A part of us wants power and gratification, and knows that the way to get those things is to murder and lie and rape and pillage. But we also know these things are wrong and hurtful.

What horror provides us, then, is a kind of bio-evolutionary life hack. We get to vicariously experience death and aggression, sadism and victimhood, from the safety of a darkened theater seat. When it’s all over, we’re left flushed with relief and gratitude and wonder.

*

Hammett can sound like a flaky rocker when he talks about the creative “zone” horror induces. As it should turn out, researchers have begun to document this effect empirically. In 2012, a team of researchers led by Loyola University psychologist Kendall Eskine conducted a curious experiment in which they asked subjects to carry out a range of activities before looking at the same set of paintings. One group watched a horror clip. Another watched a happy clip. Others did jumping jacks. The subjects who watched the horror clip dependably rated the art as more sublime than the others.

According to the researchers, “The capacity for a work of art to grab our interest and attention, to remove us from daily life, may stem from its ability to trigger our evolved mechanisms for coping with danger. Art is not typically described as scary, but it can be surprising, elicit goose bumps, and inspire awe. Like discovering a grand vista in nature, artwork presents new horizons that pose challenges as well as opportunities.”

*

Another way of saying all this would be to suggest that horror’s power lies in its ability to shock and astound us, to defamiliarize us, to make us see the world anew.

But one of the ironies I’ve been struggling with of late is the sense that horror—the effort to induce fright in the audience by means of narrative art—has become the default setting of our popular culture.

What I mean by this is that the tropes once associated with the genre have bled out from our cinemas and infiltrated the rest of our lives: our cable TV dramas, our video games, and, perhaps most depressingly, our fourth estate. Everywhere we turn, we see politicians and pundits waxing apocalyptic to gin up votes or ratings. Our news broadcasts arrive cast in a mood of rising panic and crammed with acts of extreme violence, environmental ruin, and creeping plagues.

How can horror, as a genre, persevere in an era whose every entertainment commodity is designed to horrify us?

*

It is this disheartening question, frankly, that sends me scurrying back to the strange, charmed life of Kirk Hammett.

By the time I spoke to the guy he was no longer a kid or a struggling musician. He was a bona fide Rock God and had been for three decades. The little boy who grew up spending his lunch money on comic books was now a millionaire many times over.

It should surprise no one that he had spent a small but significant portion of his fortune buying up horror paraphernalia—in particular, an astonishing trove of film posters that span the history of the genre.

As should be apparent by now, I’m no art critic. But the aesthetic power of these posters is obvious to anyone who falls under their spell. They are, simply put, stunning works of art: elegantly designed, vividly colored, and strangely moving.

I’m thinking, specifically, of the French poster for Frankenstein that shows a grim funeral procession, led by a priest, with two men hunched under the burden of a simple casket, while a pair of gravediggers trail behind. The figures rise from their own smudged shadows, as if from some lost Goya masterpiece, while a pale image of the mournful monster looms in the background, lurching toward this humble retinue, his huge clawed hands poised to snatch one of them up.

Or what about Nosferatu, as captured in an original Spanish lithograph dating to 1931? The vampire stares out at the viewer from an arched window—whether rabid or stunned, we can’t quite discern—his hand clenched around one of the metal bars that crisscross the aperture: a prisoner of his own sanguineous desires. The greenish tint of his fanged face suggests malevolence or perhaps envy, while the garish yellow letters of his name curl around him, as if even they can’t help but to devour one another.

This is to say nothing of the florid “vintage futurism” that prevails in the poster for the visionary 1927 film Metropolis, or the giant hairy arachnid whose fangs tenderly clutch a buxom damsel in the 1955 print of Tarantula!, or the disorienting Technicolor splash of When Worlds Collide (1951), whose flooded urban panorama, by some trick of tilted perspective, appears to poised to swallow up the viewer.

What’s most striking about these posters is how much pathos they generate. It’s all there in the eyes of the monsters. Consider the mask of imploration and animal mistrust worn by Lon Chaney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame, or the naked sorrow of The Invisible Man, whose peepers emerge from the darkness like glowing red coals, or the abject stare of The Wolf Man (Chaney again), descending upon his curvaceous prey and yet almost horrified by his own vulpine lust. I would be remiss if I failed to mention the glistening menace of The Crawling Eye, whose tentacles entangle a feminine morsel even as its brown iris stares down the viewer.

To take in these posters one after another is to begin to feel the buzz that Hammett experienced as a boy when, on his way to the comic shop, he would stop to gaze at the promotional posters hanging outside his neighborhood theater.

Actually, most of those posters pale in comparison to the ones he would eventually collect, as Hammett himself explained to me.

“Nowadays when a movie comes out there’s this flood of merchandise. But back then there was no TV or radio advertising, so the only thing the producers had to work with was posters. People viewed them as this disposable commodity. Everyone took them for granted. A horror poster? It’s got to be full of clichés, with Frankenstein lumbering around and that kind of thing. But as art objects, these posters are just breathtaking. That’s why I’ve spent twenty-five years trying to bring attention to the beauty of this stuff. It’s an art form that hasn’t been recognized.”

*

This, for me, is where Hammett’s relationship to horror transcends the frantic brands of mayhem that dominate our popular culture. He’s not interested in horror that merely seeks to frighten us—what the writer and critic D. H. Lawrence called “death products.” He’s interested in horror as a gateway to the inner self, to the parts of us yearning to be brought alive.

That’s what I felt the moment my eyes came to rest on one of the more recent pieces from Hammett’s collection: a poster for the 1968 classic Rosemary’s Baby.

It features a small perambulator atop a black rocky hilltop, set off against a nimbus of luminous green. For a second, it’s perfectly lovely. Then you realize that lurking within the green background is the face of Mia Farrow, the film’s star, staring upward in profile. The effect is gorgeous and haunting.

I could see, at once, that it had been the inspiration for the cheesy It’s Alive poster that had haunted my childhood. But rather than repulsing me, the poster had the effect of submerging me in a mystery: why would a baby carriage keep this woman up at night?

Or had she been awoken by a nightmare?

*

Hammett knows the feeling.

Now in his fifties, he continues to watch horror films every day. Often, he told me, he’ll sit through the first hour of a film just to revisit a particularly affecting sequence. Wherever he travels, he still surrounds himself with posters, toys, and other accoutrements of horror. They remain his creative mojo.

“I don’t get tired of this stuff. I’ll never outgrow it. Last night, I was watching a particularly intense scene and all the lights were off, and my wife walked in and I jumped, like, two feet out of the chair. And my wife said, ‘Do you know what you just did?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I jumped two feet out of the chair.’ She said, ‘You jumped two feet out of your chair and when you came down again you were trying to run.’”

Now, you could say that someone in such a state is terribly scared. Or you could say that they’re terribly alive.

That’s the feeling Hammett goes looking for every day. It’s the reason he can find the wonder of art in a set of relics that others might relegate to the trash heap of history. “My mojo is big and red and black, and it has purple spots all over it, and horns and thirteen eyes,” he told me, toward the end of our talk.

On a good day, it makes him jump two feet in the air. And when he comes down he’s running.

__________________________________

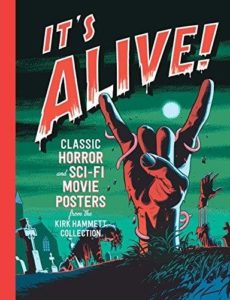

From It’s Alive! Classic Horror and Sci-Fi Movie Posters from the Kirk Hammett Collection. Used with permission of Steve Almond and the Peabody Essex Museum. Copyright © 2017 Peabody Essex Museum.

Steve Almond

Steve Almond is the author of eleven books of fiction and nonfiction, including the New York Times bestsellers Candyfreak and Against Football. His essays and reviews have been published in venues ranging from the New York Times Magazine to Ploughshares to Poets & Writers, and his short fiction has appeared in Best American Short Stories, The Pushcart Prize, Best American Mysteries, and Best American Erotica. Almond is the recipient of grants from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and the National Endowment for the Arts. He cohosted the Dear Sugars podcast with his pal Cheryl Strayed for four years, and teaches Creative Writing at the Neiman Fellowship at Harvard and Wesleyan.