On Exploiting the Labor of a Dear Friend, Who is Also a Poet

Rebecca Wolff on Publishing the Poetry of Catherine Wagner

The first time I exploited the labor of Catherine Wagner, it was 1993. We were graduate students in poetry at the Iowa Writers Workshop, and she was a year behind me, but way ahead in technological adaptation. It was time for me to submit my thesis, a manuscript whose title, “Miss November,” was a self-ironizing private reference to a song by James Taylor, and she mentioned to me that there was a “program” that would make it much easier for me to put the order together and rearrange it if I liked and then to create a table of contents and put page numbers, or, “paginate.”

Although she was busy grading her undergraduate poetry workshop—it was not common for anyone in the entire world to study what has come to be called “creative writing”—she brought me to the university library, where I had never been before, to a room in the basement, windowless, with long tables at which there were computers. I had typed my poems on a typewriter. Here things get fuzzy. I remember Cathy trying to show me how to use the program called “Word Perfect.” My memory is that she ended up sitting by my elbow as I typed the poems into a “document,” and “saving” it for me, then paginating it for me, and printing it out for me, so that I could submit it to the appropriate office so that I could graduate.

Cathy and I were both Teaching Writing Fellows, a coveted bit of merit-based aid, a status that introduced me to the industrial poetry network upon which I have ultimately labored to, with Fence, make interventions—prizes blurbs recommendations. On my first day at the Workshop another poet greeted me in the lounge with “You’re the [twiff], aren’t you?” And then he asked me who had written my letters. I had applied to only one graduate program and my letters were written by the only poets I’d ever met. I have no idea what I would have done had I not been accepted but it likely would have involved working in a health food store. I might have started my first novel sooner, had I not through industrialization become so identified with the trappings and actions and bearing of “poet.”

Catherine Wagner—known widely as Cathy—is an enthusiastic adopter of technologies. Her phone is loaded with apps. She once mailed me an envelope carefully packed with kefir grains, which transform a jug of tepid milk into a probiotic wonderland, and live in my fridge still. As a college student she won a big cash prize for her adoption of a technology that we in the 90s knew as “the workshop poem,” in which there is a lyric subject and something happens, if only in the expressed mind of that subject, and at or near the end of the poem there is a fillip of grace or revelation, sometimes produced as a declaration, what then retroactively creates the “occasion” for the poem—the occasion is the speaker of the poem learning something on the backs of the features of narrative: characters and events and the medium of language conspire or coalesce or bend over backward to provide the subject/reader with a sense of benefit, the “hmmm” of poetry readings. Something has turned a corner and blossomed, language can be musical and optical and spherical and juridical. In the contemporary lyric poem there can be a moral only by implication, which is the morality of ambiguousness: It is better when the world is bigger and less paraphrase-able. You are better when you are bigger, bigger when you are better, you are “I,” the poem.

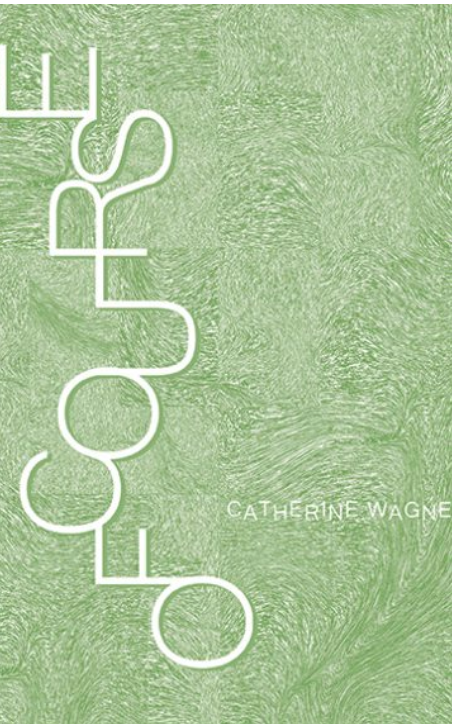

Catherine Wagner’s poems in graduate school were to some extent lighthearted. I don’t remember much foreshadowing of the gawky severity, rigorous and discomfiting, which has developed over the course of her first, second, third, and fourth books. The poems in Of Course (published officially on March 31 but launched only now because we are too busy, with union organizing and local electoral politics, literally—we have both chosen to ignore until now the needs and demands of this beautiful book because we are applying ourselves to obligations we hold to municipalities and workers) address confrontationally in a body- and language-rooted methodology the nuts and bolts, nits and grits of settler colonialism and systemic oppressions in language use, in land use and labor use. Yet there are vapor trails of the light heart in what are still lyrics but which demand, and provide, specificities. The bodied speaker lives in a particular place and has non-virtual, non-simulated, and nontransparent experiences—a walk, a cock, a conversation—and sees and hears things—crickets, pop, complicity—and relates one thing to another through her own observed systems of labor and production and valuation and collaboration, subversion and estimation. Many relationships are proposed and defined.

In one long poem the city has sex with everything, as in an old Playboy letter producing an exhausted, grateful polis. In one poem Wagner likens herself to the Amazon River after a rain storm, “Piranhas climb up your pee stream / when you pee into it.” This is not the flaccid 90s move of indeterminate lyric self-definition, for Wagner is in relation and recognizing the relations of power, material conditions, and bodies within. She also recognizes language traditions, and subverts them too, not in received subversion but in a specific bodied formal vocabulary of presence in minutia, her close reading of the labor of reading the garden, reading and writing the leaving of the garden to trespass on the golf course, for example.

In the periphery I was secret gong

hanging the hammock thinking CALL MY MOM

not doing that or any other task ha

HA I’ll do my job of

putting head outdoors the garden ringing

unfocused my eyes allowed

moving shadows on the lawn

like baby whales playing 20 feet underwater

to shift their noons

*

dang it I can never see the crickets.

Squatted by pond to spot a couple of disco frogs and a cricket I thought

was very close. I didn’t see any of them but did see spider, tiny beige, tie

a web between grasses. The frogs talk, maraca speed slowing to plucked-

string: “That’s-how-it-is; that’s how it—is; is is—that’s how it is is is is is—

that’s how it is. That’s how—it is.”

After Iowa, Cathy Wagner smartly became a doctor of Creative Writing, and prepared herself to labor. I was on a miscellaneous path involving a brief foray in graduate study and a lot of temp work while I started the literary journal Fence. I would not have thought of Fence if I hadn’t met poets in graduate school whose poems were, as were mine, straining in form and gesture at the limits of the bourgeois lyric and the less cool, more conforming narrative, yet not directly relating to the aims and forebears of what was then called “experimental poetry.” What I was urgently concerned with was the way I directly observed, with my self-limiting understanding of what was at stake in any aesthetic-social alignment, that the actual poems that got published as a consequence of their social-aesthetic alignments were not necessarily very good poems. I was into an aesthetic disconnectedness that perhaps only I could see because of my own disconnectedness—or perhaps only I could only see it because it wasn’t there. I wanted a disconnectedness of social relation as well.

The longer I was in graduate school and the contexts thereafter the less I liked the way you could see the wires of what is called variously “community” “coterie” “nepotism” running from thing to thing, who got what, what allegiance announced through what publication, what book got picked, jobs and prizes and sparkles. (What was invisible to me: admiration. Shared principles evinced in shared aesthetics; kinship expressed through likeness.) I wanted an autonomy of art object and I wanted a dissolving of social networks (and then came social media lmfao). I wanted people to be honest with one another about whether their art was any good, no matter what their interrelation. Maybe they were student and teacher. Maybe they were reading the same books. The pivot of love for a thought leader that would lead to a mutual appreciation, or a fan club, or a following—I did not feel it.

I did not productively admire any poet and I did not share with Cathy Wagner or any other poet an expressed love for any progenitor of poems who would lead us into our own poems. Those whose poems I had felt love for as a student—the list is short: John Ashbery; Clark Coolidge; Marjorie Welish—represented for me nothing but an aura, unrepeatable. In short I considered poems, or the minds that create poems, as being imaginaries distinct from political or social objects. My strong unconscious tendency was to turn away from teachers/elders and otherwise spurn any offer or availability or relation. I guess with hindsight I could say I wanted to burn it all down. I wanted a meritocracy, it is possible to say, and I did not understand almost anything about what was wrong with that concept or its underpinnings—smh. It is too late to go back to the past and mutually aid the aesthetic communities large and small I have failed to join or form. However for better and for worse I have maintained a structure (Fence) in which editors deliver their attention fully to the writings of people who they don’t know and who are consequently not their friends.

When Cathy became my author it was 2001, and she had submitted her manuscript “Miss America”—related only in ironic volume to my title—to the first round of Fence’s book contest now called the Ottoline Prize. Because she was my friend I did not want to give her the prize. Because her book was great I wanted to publish it. I was confused only for a short time about what to do, and I selected another great manuscript to win the prize (Chelsey Minnis’s Zirconia) and published Cathy’s as well. These were the first two books Fence published. The three of us rented a minivan and went on a road trip, Southwest to Pacific Northwest and back, in which we read upwards of 30 times.

My first book of poems had been selected in 2000 to win the National Poetry Series. For many years after I had a plan to write a kind of exposé of my own direct experience of aristocracy, or whatever is the opposite of meritocracy, but I don’t know what there is to say about it other than what I am saying now. Manderley is a more-than-decent book of poems and maybe worth publishing but would surely have gone unnoticed if my name was not attached to it and to Fence. The vacuums do not exist. Perhaps the vacuums are stocked with mutual aid. I brought Manderley to my best friend’s mother’s dying bedside the other morning, and was not overly moved by my stilted poems but was moved by her saying to me out of her delirium that she would “listen to me with her whole heart.” Unlike my friend’s mother the latinate mannerism of my early poetic utterances has not aged well—I had identified too closely with Henry James. I wish I had read her my better poems, or the poems of a better poet.

Cathy and I bore children in the early oughts, and with our collaborators we visited and dreamed of making a school in the Hudson Valley for unaccredited poetry and visual art—a school that would provide the conditions for conversation. We came approximately 1/5 of the way toward dreaming it into being, scoping out towns and properties, but exigencies at that time proved persuasive for Wagner and her family to continue in the academy. A couple of twists later, and I had removed to the Hudson Valley for what has now been an eternity and Cathy has been a professor of poetry this whole entire time and the institution of creative writing has mounted an industry of pedagogy and capitalization, has formalized so many relationships within that structure, and the blurbs and prizes and recommendations primitively accumulate even while their distribution has shifted toward equity and racial justice, to some degree in alignment with the academy.

If you follow Cathy Wagner on social media you will know that she isn’t on Instagram or Twitter and her “intro” on Facebook says “Rarely post here. I post over on the Miami AAUP Advocacy Chapter group and page. Solidarity!” I love following her posts over there in solidarity because I love seeing the working end of her rigor as it is deployed over the rights of the contingent and adjunct faculty at her university. As she says in her poem “Impersonal Lubricant”:

If you’re not part of

the solution, dis

solve for x: turn into oyster—

filter phosphates, nitrates, ammonia,

bacteria, plankton into

pellets of harmless nitrogen.

Be brilliant machine.

Keep water clean.

But when the sea turns acid

I can’t build my shell!

Lately when I talk to Cathy on the phone she tells me that she has been unable to stop compulsively labor-organizing. A typical post in Cathy’s other language says, “Student debt is a faculty problem. See the excellent “Refusing Austerity in Higher Ed: A How-to Webinar” https://buff.ly/36BtCvq @AlexisGoldstein 20:30, Nick Mitchell 31:38”

We share the position that there is no choice but to participate in action against racial capitalism at this time.

I remember a long phone catch-up we had in the summer after the Election which culminated in our quick agreement that we would put our bodies on the line in an antifascist context. Cathy has always included her body in her poems, it is a device for song: “So folded, tired, I will sing the differences / between plant and plantation / and factory and fact.” And, via negativa, in a poem titled “I was raping things that didn’t matter, ”—“ . . . that’s how / I paid down debt / when I was tied spread-eagled / to the blades of a huge steel fan. / My soft teardrop boobs hang down / A field of babies on the gym floor / needed to be fed / and I was too high up.”

As Cathy’s publisher it is my job to make her book known; as her friend it is my privilege to know her intimately; at the intersection of publisher and friend is the real, the conditions we choose not to ignore. I hope she will approve this formulation. Fence labors to gather visibility so that it can conserve and amplify weirdos like Cathy. Her twisty, internal-external, mobile, personal, political poems are driven by impulses to investigate (look under), narrate (a little known partial story), interrogate (reel from the obvious), and witness (be there now), in a mode that is hardcore and dear.

_________________________________

Catherine Wagner’s Of Course is available now from Fence.

Rebecca Wolff

Rebecca Wolff is a contributing editor to Lit Hub. She is a poet, fiction writer, and the editor both of Fence magazine and of Fence Books. She is a fellow at the New York State Writers Institute.