On Disrupting a Cherished Musical Tradition and Creating New Appalachian Ballads

“No music will live if it is treated like a museum piece.”

As a publishing company with its main location in southern West Virginia, Blackwater Press is undeniably an Appalachian press. That means when we receive manuscripts from regional writers or on regional topics, I’m not automatically open to acceptance.

Quite the opposite: I’m more critical than I would ordinarily be.

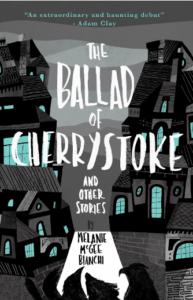

This is because Appalachian literature is problematic. It tends, generally speaking, to focus on themes of poverty and abuse, to romanticize retellings of old ballads, or to be mired in sentimental nostalgia for the good old days. When I received the manuscript of Melanie McGee Bianchi’s collection The Ballad of Cherrystoke and Other Stories, though, I was cautiously interested, because it seemed to be none of those things.

The Ballad of Cherrystoke and Other Stories doesn’t play around with old lore. It creates new ballads, rather than invoking the traditional ones that have existed for centuries.

My background and professional research is in 18th-century Scottish studies, specifically music, but ballads rarely come into my work beyond a ballad opera or in the form of a published version for a polite drawing room. I moved to Scotland in 2011 as a PhD student at the University of Glasgow and lived there for eight years as a student and postdoctoral research, immersing myself in ballad history and landscape whenever I could.

Thomas the Rhymer’s wood. Image courtesy of Elizabeth Ford

Thomas the Rhymer’s wood. Image courtesy of Elizabeth Ford

My formative reading was made up largely of Scottish myth and faery tales and modern novels based on ballads. The dark, morally ambivalent beings of Scottish lore were so real to me the first time I was alone in a Scottish wood I kept seeing a shape cloaked in green moving just out of my line of sight. The first time I went to Bowhill to look for Tam Lin’s well, it wasn’t there. The three horses, one white, were, but no well. The subsequent two occasions the well appeared, tucked in the ground among ivy and moss as if it had been there for centuries.

Another time I was walking from Melrose, near the Eildon Tree, to the village of Earlston to see Thomas the Rhymer’s ruined tower house and the Ercildoun plot in the churchyard. I wound up going in a circle in the woods, my camera suddenly stopped working, and when I arrived at the churchyard, I had a distinct feeling of being followed and laughed at. I left without finding the famous “the rhymer’s race is in this place” stone. When I hear church bells I wonder if they’re tolling for disagreeable and ill-fated lovers such as in the many versions of “Barbara Allan.”

So indeed, given this predilection (obsession?) I was intrigued by the title of Melanie McGee Bianchi’s book. But The Ballad of Cherrystoke and Other Stories doesn’t play around with old lore. It creates new ballads, rather than invoking the traditional ones that have existed for centuries. I was ready to find something wrong with the book, but almost immediately decided I needed to keep reading.

The story that unfolds is about a young woman, Siobhan, who has suffered a traumatic brain injury that has changed her intellect, her body, and to an extent her personality. She works as a maid at a mountain resort. Her twin—actually, her stepbrother—is Shad, a freight-hopping banjo-playing drifter, who is determined to be more authentic than authentic in his embrace of a rambling life and the culture surrounding Appalachian old-time and Celtic music:

He had the knowledge of the old music, how it came from Ireland and Scotland to infest itself in the Southern mountains. He wore a Celtic cross necklace, this winking hunk of pewter.

This was not the sentimental, nostalgia-laced narrative I had expected, nor was it a modern retelling of ballads, as is frequently the case when ballads are used as the basis for contemporary writing. It appeared to me to be something totally different.

The lake pulled down Appalachia in one rush—this lamenting purple-green sunset—before night folded in. It didn’t even have to be a full moon. Once it was properly dark, my brother and I sat on our little deck and listened to the foxes sweetly threatening their own mates across the water, these harsh kitty cries. Later on, it was screech owls, and hard to tell the difference.

The Appalachian Mountains were settled largely by immigrants from Scotland and Ireland, and, to a lesser extent, England. The poor from these Celtic countries were accustomed to harsh conditions and unforgiving land, so the complete lack of flat land and heavy forest may have been a welcome change. They brought few material possessions with them, but traditions, stories, songs, and tunes don’t take up much space in a ship’s hold.

Between 1916 and 1918, the English folklorist Cecil Sharp, with his assistant Maud Karpeles, travelled the Appalachian Mountains collecting ballads from largely untrained rural musicians. They even made a stop in Ronceverte, West Virginia, where I like to think they encountered my very musical great-grandfather, Andrew Reaser, who worked on the railroad.

Respect for tradition-bearers is of vital importance to the understanding of cultural heritage, but no music will live if it is treated like a museum piece.

Sharp believed he had discovered a hitherto unknown or unrealized pocket of 18th-century English culture. The songs he was collecting were the same ballads he had collected in England, and the same published by Francis James Child between 1882 and 1898. The tunes varied, the words varied, but they were the same ballads. Sharp thought he’d found a tradition preserved intact, whereas he had discovered that the songs he knew still lived but with the influence of other, non-British, non-white musical styles.

Tam Lin’s Well. Image courtesy of Elizabeth Ford

Tam Lin’s Well. Image courtesy of Elizabeth Ford

And that’s a problem with traditions, “traditional” music in particular. A point seems to come at which only the ideas of preservation and authenticity and accuracy are valued, ignoring that traditions have evolved over time and that, in order to survive, they must continue to do so. That the same ballads survived for so many centuries across so many cultures and countries shows an interest in keeping the stories relevant for each generation, but in contemporary musical culture, ballads appear to have stopped evolving around 1960. Respect for tradition-bearers is of vital importance to the understanding of cultural heritage, but no music will live if it is treated like a museum piece. A ballad or a tune can be said to be traditional, but only if it is old. This should then lead to questions regarding whose tradition is being preserved, and on what authority.

“What’ll you have, Shiv?” he said, drawing himself up cross legged, picking up Little Miss but facing the possum a bit, too, like he was singing to both of us. “‘Omie Wise?’ ‘Pretty Polly?’” “No,” I said, slowly. “No murder ballads. No dead girls.” He hummed and strummed, pondering, before continuing a song of his own he’d been working on. His voice had gone raspy, sleeping under the air conditioner so long.

I don’t want to go to Cherrystoke.

I’d rather be here, and I’d rather be broke.

I’ll ride the rails and I’ll be free.

I’ll find some old gal to ride with me.He sang in his lightest register, because of the wild animal in the room. I listened with my eyes closed. “‘Old Gal’ sounds stupid,” I told him, and he nodded, setting Little Miss aside and reaching for his bag of tobacco.

Little Miss is the name of Shad’s banjo; a baby possum has snuck into Siobhan’s room. Bianchi only gives us one verse of “The Ballad of Cherrystoke”; rather than rehash or recycle the same old ballads, she has created a new one, that could easily slip into the repertoire.

The story “Abdiel’s Revenge” concerns a Russian ex-con who lives with a woman who is twice his age. Her family has inhabited the local landscape for centuries and has its very own murder ballad, about the much younger wife who, nearly two hundred years earlier, one day had had enough of her domestic situation and in the dark of night set fire to her loathed mother-in-law before drowning herself in the river that features in the story’s contemporary framework.

Unusually for the ballad motif, it is the woman who does the killing. Bianchi provides nothing specific from this ballad except a ghost of context: the random, shocking act mirrors aspects of the passion and violence to be found all through “Abdiel’s Revenge’s” modern, intertwining plot lines. And yet her made-up “traditional” ballad could easily take the shape of “Edward,” or “Long Lankin,” or “Lord Randal,” or the infamous Frankie Silver murder case of Burke County, North Carolina.

In creating these two new ballads, Bianchi has enriched two traditions: Appalachian literature and music. Rather than reframing or updating known stories, she has created entirely new ones that fit within the existing traditional paradigm and could easily be taken up by a songwriter and slipped seamlessly into the repertoire. Whether or not they ever achieve the soubriquet of “traditional” is another issue.

“The Ballad of Cherrystoke” and “Abdiel’s Revenge” have been written by Pete Kosky for a collaboration with Bianchi on the use of ballads in literature.

_____________________________________

The Ballad of Cherrystoke and Other Stories by Melanie McGee Bianchi has been listed as a Distinguished Favorite in the 2022 NYC Big Book Awards. It is available via Blackwater Press.

Elizabeth Ford

Elizabeth Ford dropped out of law school to pursue a PhD in Scottish music at the University of Glasgow. This research won the National Flute Association Graduate Research Award. She has held (and will hold) research fellowships at the University of Glasgow, the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh, the Riemenschneider Bach Institute, the McGill-Burney Centre, and the Bodleian Libraries. Her writing is widely published in the fields of eighteenth-century Scottish studies and historical musicology and has been called "required reading." Her work in editing started when she was employed by her family’s physician to assist as he wrote the great American novel. Since then, she has worked with writers of fiction and non-fiction, copyedited for the Legal Studies Forum, worked as the English language editor for Schott Music, and was managing director of a small press in Glasgow. She is currently lead copyeditor of ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts, 1640-1830.