On Discovering the First Fossil of a T. Rex

In Hell Creek, Montana, With A Lot of Dynamite

As the last days of July 1902 ticked away in Hell Creek, Montana, Barnum Brown found himself torn. The party uncovered a Triceratops skull that was in decent condition, though its horns were missing. With enough work, it could be “a fine exhibition specimen,” he wrote to Osborn, knowing that would begin to make up for the crushed fossil now sitting in the museum in New York. If anything, the skull would buy him at least one more year of employment.

But he wanted more. Never one to be satisfied with what he had in hand, Brown felt compelled to brave another ravine, search another hillside, climb over the side of another cliff if doing so meant that he would come closer to a specimen that would put the trajectory of his life back on its upward tracks. As the temperature soared above 100 degrees, Brown worked without stopping, the contours of his face slowly disappearing behind accumulated layers of grime and dust.

Since childhood he had acted as if he had an unspoken trust that the universe would bend in his favor when he needed it. Each morning he stepped out of his tent seemed to be another plea that his luck would return.

As July faded into August, Brown attacked a sandstone hill he called Sheba Mountain with a plow and scraper, determined to satisfy his curiosity about what lay beneath. Its particular composition of stone and its location near what was once an inland sea fit the profile of a promising fossil bed. Once Brown began to dig, however, the rock proved incredibly hard, seemingly impervious to any blade. Unable to let it alone, he sent an assistant to Miles City to come back with enough dynamite to blow off all the hillside above what he hoped would be the bone layer.

Brown was not in the habit of blasting away at every spot that gave him trouble, but this time—whether due to frustration, intrigue or a combination of the two—he had to know what secret the Earth was protecting with such ferocity. He laid the explosives, set the timer and waited. The blast echoed among the ravines of the badlands, reverberating like distant thunder. A dark cloud of dust and dirt hung in the air, so thick that he could taste sand on his tongue.

Once the smoke cleared, he edged closer to the lip of the quarry, staring into the deep hole he had created. It was nothing less than a time machine, bridging the 60-million-year gap between the age of the dinosaurs and our own. As he looked down into the pit, Brown took in a shape that no human being had ever laid eyes on. “Quarry No. 1 contains the femur, pubes, [partial] humerus, three vertebrae, and two undetermined bones of a large Carnivorous Dinosaur not described by Marsh,” Brown wrote in a letter that evening to Osborn. “I have never seen anything like it.”

It was as if a child’s conception of a monster had become real and was laid down in stone.

It was as if a child’s conception of a monster had become real and was laid down in stone. Though most of its skull and tail were missing, everything about the beast seemed designed to overwhelm the human mind: its hips, nearly 13 feet above the ground, would later be found to power legs that ran at speeds greater than 10 miles per hour; its immense jaws measured over four feet in length and could exert as much pressure as the weight of three modern cars, instantly exploding the bones of its prey; its serrated teeth, the longest of any known dinosaur, could dig through the thick skin of a Triceratops and rip out five hundred pounds of flesh in one bite.

In time, the creature would become perhaps the most recognizable animal the world has ever seen, its deadly silhouette and Latin name familiar even to those with no interest in dinosaurs or science. Yet in that moment in the hot August sun, the animal that would soon take the name of Tyrannosaurus rex was entirely new—an unmistakable set of clues that the history of life was more varied and surreal than anyone had imagined.

Brown knew that he was suddenly in a race against time. He had found the only specimen of a creature previously unknown to science, and there was no telling if he or anyone else would ever find another. With less than two months before the broiling landscape would become too cold to allow work to continue, Brown scrambled to uncover as much of the fossil as possible.

A September snowstorm was not out of the question, which could mean that the dinosaur might have to be abandoned over the long winter and spring—enough time that someone from Jordan could pick up on rumors of its discovery and try to sell it themselves, or, even worse, destroy it through carelessness.

Brown rode his men hard, his natural cool reserve vanishing under the demands of an unrelenting taskmaster. The small general store in Jordan soon ran out of lumber and plaster, the two supplies most essential in extracting a gigantic fossil out of the ground without damaging it. With no other choice, Brown turned to dynamite, taking the risk that the surrounding rock layer was dense enough that he would not accidentally blow up the fossil before he could share it with the world.

“The bones are separated by two or three feet of soft sand usually and each bone is surrounded by the hardest blue sandstone I ever tried to work in the form of concretions,” he wrote to Osborn in September, after nearly a month of nonstop digging and prying. Each day, more of the animal was revealed, like the wrapping paper of a gift being removed inch by inch.

It would be two years before museum technicians fully cleaned and prepared the skeleton of the T. rex.

Finally, in October, Brown pulled the last section of the skeleton free. The small team of horses strained under the load, pulling the haul to Miles City in shifts, eventually moving more than fifteen thousand pounds of bones to a boxcar that Osborn had arranged for them. As the first snow of winter fell, Brown watched as nineteen crates of fossils were loaded into the boxcar, a collection that included not only the new carnivorous dinosaur, but also the skeletons of a crocodile-like Champsosaurus and a Triceratops—both of which still stand on the floor of the American Museum.

Though he knew that its contents were priceless, he did not accompany the train east. A prospector at heart, he could not leave Montana without poking his head around for at least a few days more. He soon walked into the lobby of the Billings State Bank on a small errand and, while waiting in line, noticed a display case containing the oversized limb bone of a dinosaur. A brief talk with the bank’s manager revealed where the fossil had come from, and Brown spent the final days of the year camped on the banks of Beavers Creek searching for the remainder of the specimen.

When the train carrying the crates from Jordan reached New York, Osborn did not realize what he had. It would be two years before museum technicians fully cleaned and prepared the skeleton of the T. rex, removing each piece from the matrix of stone and arranging them all in a fully articulated skeleton. Until then, what in time would become the most famous dinosaur in the world looked no different from every other fossil Brown had found, encased in a cocoon of white plaster with the letters AMNH painted in black on its side.

With nothing to quell the sense that he was losing the fossil race, Osborn remained preoccupied with the Carnegie Museum and its Diplodocus, unable to see the magnitude of what Brown had discovered. “I think we have the finest carnivorous Dinosaur material in the world; but I envy the Carnegie Museum their complete skeletons. Mr. Hatcher writes me that they have found a magnificent Diplodocus which seems to be almost perfect,” he wrote in a letter at the end of the prospecting season. “We are certainly not holding our own . . . both Carnegie and Chicago have done better than we have.”

____________________________

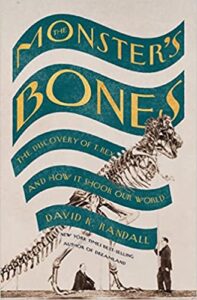

Excerpted from The Monster’s Bones: The Discovery of T. Rex and How It Shook Our World. Copyright (c) 2022 by David K. Randall. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

David K. Randall

David K. Randall is the New York Times best-selling author of Dreamland, The King and Queen of Malibu, Black Death at the Golden Gate, and The Monster's Bones. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Los Angeles Times, among other publications. A senior reporter at Reuters, he lives in Montclair, New Jersey.