On Being a Young Reader Attracted to the Darkest

Possible Stories

Estelle Laure's Search For Challenges to Her Comfort

When I was twelve, there was a serial killer in my Bay Area neighborhood, comprised predominantly of retired couples. He followed them home from the grocery store, covered their heads in plastic bags until they asphyxiated, then robbed them.

We lived two blocks from the store. I would watch those nice people watering their lawns, waving, and picture them being ambushed. I can feel, right now, what it would have been like to lope home along the train tracks in a neighborhood under curfew, being actively stalked—how peaceful and horrific and how full. How alive.

I went to school in San Francisco and spent hours reading on the train, so much Stephen King that on my fourth round of Firestarter my mother took my book and told me I was going to be permanently fucked up if I didn’t stop. I yanked it back and told her it wasn’t the book that was going to do that to me, because look around. I already felt damaged and distorted by everything that had happened to me in life, and those books gave me agency. Stephen King hadn’t warped me; he had gifted me something. He told me the truth, not about little Charlie who set things on fire, but about violence exacted upon the weak by the strong. With him I had found some sort of communion, a more extreme version of the brutality in evidence all around me. No, his books said, it is not you who is damaged, but the world itself.

After Stephen King, I positively careened into my dissection of the underbelly. It seemed to be everywhere I looked. I didn’t understand how people made small talk and worried about table manners and posture when there was chaos everywhere. From a very young age, human behavior was nonsensical and stories that revolved around evil revealed what everyone seemed so busy trying to hide. I was always repressing the urge to scream, to break the illusion, to shatter the glass that existed between everyone else and me.

I was a perpetual outcast: poor from a rich family yet I had never thought about class; white with Buddhist parents and I had somehow never given thought to race or religion. I felt simple, rejected, untethered from the world around me, floating somehow, and stories that told me the truth grounded me. I had questions and only books were brave enough to give me answers.

I have been reading violent stories since I learned how to read at all, not because I’m a proponent of violence, or because I fetishize it, or because I like blood and gore. I don’t. It wasn’t only horror that provided solace, though those books were cathartic. The year I was twelve I also read I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Lord of the Flies, The Outsiders, The Color Purple, Of Mice and Men, each one revealing a little more.

Still, people have questioned why I dwell in darkness, why I like twisted plots and books that are considered depressing. I’ll venture to speak on behalf of readers like me: We read those stories because they don’t lie. They show us the scorpions and the worms under the rock. In doing so, those books make us kinder, more aware, more compassionate.

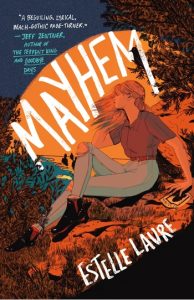

When I started writing my young adult book Mayhem, I drew from my time as a kid living with constant threat. My home life was a disaster with chaotic adults at the helm. My neighborhood hung heavy with dread. And I put one foot in front of the other, listening to The Cure and nodding to the guys who hung out under the tracks smoking. It smelled like California, and it tasted like Wet n’ Wild lipstick. It was as true as anything could be and it was so, so quiet.

As an adult, things have changed. I don’t feel the same righteous indignation I once did. I understand now why we try to maintain societal niceties, that it has to do with the aspirational survival instinct in all of us, that we can train ourselves to be better people and there’s no point in making every second heavy with existential dread. There’s room for laughter and optimism and self-improvement, and the world is so gorgeous it’s a permanent ache. It’s important to remember there’s also a fine line between optimism and denial. Writers tell that truth through the lie of fiction, and now those stories are more necessary than ever.

With the country moving toward reopening and everything that’s come in the last months, I’m caught in a permanent state of sentimentality, on-the-nose words of love hovering at the tip of my tongue. The world is a pastel dreamscape. I’m always on the verge of tears, not only because of grief; I’m overwhelmed by the beauty I see everywhere and by everything I’ve taken for granted. This is full-frontal fierce grace.

As is always the case following periods of tragedy, we’re going to reach for relief, humor, fluff, and we should, but the world also has a hype hangover and is in deep need of stories that reflect what it knows to be true.

Writers have always explored the taboo and nuanced, but now we have a mandate to reflect the truth: life is pain, but pain with purpose, the purpose being to try to understand ourselves so we can do better. Our relationship with adversity is tragic—we need it in order to rise, smooth out, and shine. Stories can take us to that place at the turn of a page, can transport us to the root. So maybe now I don’t read so much for bloody catharsis, although I indulge from time to time because I do love to see a bad guy go down. I look for what will challenge my comfort and belief systems, what will widen the scope of my understanding and humble me, and sometimes I look to face a monster, even if it’s the one in me.

__________________________________

Mayhem by Estelle Laure is available via Wednesday Books.

Previous Article

What It's Been Like to Run the First American Diner in ParisNext Article

On the World Buildingof Gardens