Of Wazhazhe Land and Language: The Ongoing Project of Ancestral Work

Chelsea T. Hicks on the Land Back Movement and Working Toward Rematriation

In January of 2022, I traveled to ancestral Wazhazhe land in Belle, Missouri, where an arts organization had invited me to do a residency while assisting in giving the land back to the Osage Nation.

The terms were such:

The owners would not leave their land;

The arts organization there would still double as a small ranch;

The administrators were not open to collaboration with Wazhazhe people on any of their operations or programming;

And the organization wanted me and any Wazhazhe artists I involved to instruct them in

the manner of giving the land back.

The arts organization told me their land repatriation was not connected to any of the arts organization’s activities, or even their occupancy of the land. I did not want to help them. I wanted the chief to help us. The settlers would remain on the land until death, and they had told me so to my face. I was angry. Alone in my studio, I tore up a document they’d asked me to read and to endorse as a Wazhazhe woman artist. I screamed and wept.

Later, I asked the arts administrator if he knew of his ancestors. He said that had never heard of any of them, and instead considered himself to be from Egypt in his “past lives.” The spiritual sidestepping of his ancestral connection was problematic; his disconnection absolved him of responsibility to his mother land, and by extension, to my own as an earth keeper. I could do little but witness his guilt.

When a person rejects a Christian framework but replaces it with appropriation, one is still functionally inside the legacy of Christianity’s westward expansion, and does nothing to protect the land. Although the contemporary culture has dissociated itself from its origins, our origins remain, in the exact conditions in which they were abandoned. The Land back administrator was able to make so-called separations between deeply connected things such as his arts organization named after our tribe, and the land on which it sat.

“The land and the organization … they’re not related,” he’d said.

This was a man who claimed to hear my own ancestors speaking to him day in and day out, and who said they shot arrows at him whenever he entered or exited a house on this land.

He felt the enmity between our ancestors. So did I.

In Earth Keeper, N. Scott Momaday writes that a pioneer woman and her ancestors experience “belonging” on this earth. I asked my students at the Institute of American Indian Arts to vote, as though on a committee, on whether settler people should stay or go (if Natives had a choice). After discussion, we agreed that we did not believe European people would ever leave, and if they became earth keepers, it would be possible for us to collaborate. We thought, if more Native people go into leadership, like Deb Haaland has, then our views will gain real credence.

Every morning, I sit cross-legged on a pillow by the cracked window and imagine the sides of my body turning two opposite colors, one red, and the other blue, to represent balance between earth and sky, and the way that I contain both body and spirit. Every person has this duality within them, but many people are invested in a sense of victimhood. We forget our motherland. Among my ancestors are European people, and as a mixed Indigenous person, I am forced into leadership.

Before my European ancestors were in England, as Normans, they were in Northern France. Although I have no current place there, I do believe that I have a responsibility to this land, even if I have not yet ascertained how. Part of my spirit rests in that land, and my responsibility to it also lies in its waters. My time on Wazhazhe land is only a part of my total rematriation.

I don’t like any erasure of ancestral work, but I understand that the land itself may support this work better than any book, ideology, or education.

On my mother and her mother’s side, my ancestors are from New Orleans. They are “mulatto” according to the census, which is generally defined as an erasure-based mix of Indigenous, African and European ancestry. My mother did not acknowledge her matrilineal lineage, but immersed herself so wholly in her faith that, to me, it seemed like an addiction: it provided a false solution, and prevented her from having to transform. The concept of sanctification seemed like absolution to me, and the delay of a so-called perfection into eternity. I looked for matrilineal reconnection but it seemed a betrayal of my mother and her mother.

I do not consider any person separate from the responsibility of our own generational trauma; rematriating to the lands from which we first came; honoring as well as mourning the actions of ancestors; and resolving our part in conflicts. Without these four actions, we lose connection. I prefer to maximize connection, in the way of Rainer Maria Rilke, who writes, “Everything that makes more of you than you have ever been, even if your best hours, is right.” Sometimes this means syncretization, or the blending of Indigenous and Western culture, as N. Scott Momaday has advocated with the building of metaphorical bridges between our worlds.

When it comes to the Land Back movement, how will our pragmatism play out in keeping the earth? Our Indigenous tenure is more legitimate than that of settlers, but if we choose to work together with those make earth keepers of themselves, will we be able to protect this land? I am inspired by a radical Black farmer who told me that it’s not one’s identity, it’s what one believes. I don’t like any erasure of ancestral work, but I understand that the land itself may support this work better than any book, ideology, or education. Though I did not call the chief, I stay in conversation with ancestral water. The river absorbs my rage.

__________________________________

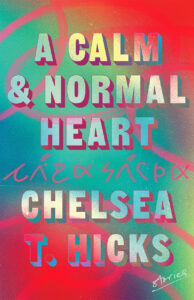

A Calm & Normal Heart by Chelsea T. Hicks is available now via Unnamed Press.

Chelsea T. Hicks

Chelsea T. Hicks’ writing has been published in the LA Review of Books, The Paris Review, McSweeney’s, the Believer, The Audacity, Yellow Medicine Review, Indian Country Today and elsewhere. She is an incoming Tulsa Artist Fellow and a recent graduate from the MFA program in creative writing at the Institute of American Indian Arts. She is a 2016 Wah-Zha-Zhi Woman Artist featured by the Osage Nation Museum, a 2016 and 2017 Writing By Writers Fellow, and a 2020 finalist for the Eliza So Fellowship for Native American women writers. She is an enrolled citizen of the Osage Nation and she belongs to Pawhuska District.