My research on the tongue was divided across the equator, the exhaust offset. In the northern winter I hurtled south towards the summer, to Split Point | Wathaurong land. The cabin lights will be dimmed for landing. “Research” comes from Old French recercher which means “to search closely,” from cercher “to seek for,” through Latin circare, “to wander, traverse,” from circus, for circle. Returning to that divided kingdom a few weeks later, London glinting below as bared teeth, over the speaker would come the refrain: this is customary when flying in the hours of darkness.

The roads were icy that February morning and the sky overcast, and the temperature scarcely rose inside the library. I was following a lead on a pamphlet popular in 19th-century New York called The Tongue of Time. It covered the natural and spiritual worlds, disease, witchcraft, trances, dreams, death, diet, serpents, opium use, the childbearing of older women, mouth care and hygiene, accounts of people with two souls, and the universality of deception.

With each flight the stairs narrowed, spiraling inward until I stepped out into clouds of my own breath. Through the slat on the landing a hard sunless light, livid in color, was moving along the floor, over drifts of books known as the overflow. The landing felt as though it were shifting ever so slightly from side to side, doubtless a psychological effect of the spiraling staircase and the narrowness.

And I had been told that, so close to the tower, the sound of the wind alone could produce that effect, the effect of an edge, vertigo, as standing on the end of a pier. It felt familiar, the volatility that pervaded everything I read about the organ. What was the human tongue? The last animal of the face’s reserve. Through the slat I saw a sail of white birds lift and fall up and beyond the brickwork.

I had until that morning been looking for stories of women, saints or otherwise, whose tongues had been cut out at the root. In many of these tales, speaking again after the violence is the point of the story (it’s a miracle) but I was redirected when I came across The Tongue of Time. The archive boxes were arranged in dim rows extending from a main corridor, strings of dormant cells. The light there was controlled by a timer, itself a bone-neon more commonly found in hospitals and apartment complex stairwells. I turned the dial and the minutes began to run down.

Some of the boxes had ink markings from previous systems, disintegrated letters and numbers the color of sandstone. I found The Tongue of Time and sat on the floor with the overflow to read it. When I finished I made a brief note for reference, in case I needed to revisit the work in a year or two: Stories, mainly allegorical, myths, moral directives. The tongue is employed as a metaphor for the extension and consumption of aeons, the way time laps at one’s heels. It contains conflicted and disparate worlds, confessions, issues and arguments of all kinds. I placed the pamphlet carefully back in the box and returned it to its cell.

The tongue is employed as a metaphor for the extension and consumption of aeons, the way time laps at one’s heels. It contains conflicted and disparate worlds, confessions, issues and arguments of all kinds.My relationship with the tongue began with an incision made on my father’s body. He was leaning on the drip looking bad enough to be redeemed. The hot purple wound ran from his solar plexus to the base of his gut—in medical terms, an incision from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis. To the eyes of a child he had been opened along his length and stapled back together. And I felt it then, soundless, the stuck muscle in my mouth become stone. This was a long time ago.

Towards the end of his life my father would sit in the garden and I brought him things he could eat. The last thing he could eat was soft bread. “Break it into pieces,” he said, and I did as instructed. What voice would I have needed (were there words I could have used?) that might have opened a final kindness between he and I. But here are his arms in sheets of skin outstretched for the bread, our faces set. And the vapor of my voice held for so long it alchemised into feeling: the relief of his becoming weaker.

Break it into pieces. They were the last words he said to me. The word “archive” comes from arkhē (ἀρχή) Ancient Greek for “beginning place” or “point of origin.” Meanings evolved to ‘written records’ and the public buildings in which they are kept. Archives are patient, dependent on care and active listening for creation and survival. To assemble an archive is to piece things together. But its parts gesture to how much we cannot know, to how much is missing and may not be recovered. Go far down into the word ἀρχή and you find water. The root comes out at the ocean, or rather the cosmic ocean—a yawning elemental chaos from which all supposedly emerged.

In the library café, on my break, I read in a magazine that our oldest and most primitive vertebrate ancestor Saccorhytus coronarius was a big mouth with no anus. Fossils from around five hundred and forty million years ago reveal its mouth-body was no bigger than a grain of black rice. This first creature was covered with a thin skin and lived in the sands of the seabed. It is unlikely that Saccorhytus coronarius is a direct human ancestor, but the creature tells us about the early stages of our evolution—it had bilateral symmetry, two symmetrical halves.

Of women’s mutilated tongues, I had a particular interest in stories where the breakage was self-inflicted. Self-muted and deeply bitten, sacrificed in order to save something else. In effect, self-censored to prevent what could come to light. Like the story of Tymicha for example, in the Syrian philosopher Iamblichus’s Life of Pythagoras which dates to the sixth century BCE. Persecuted under the tyrant Dionysius, she bites off her tongue when threatened with torture. Tymicha then repurposes the organ as a physical weapon and spits it at him in defiance. The story makes it clear that, being female and prone to talkativeness, she breaks her tongue because she might not be able to govern it, and may instead be compelled to disclose something that ought to be concealed in silence.

For years, being quiet, I felt clear. Clear and cool. I tended the lies of others—I packaged them like cold cuts and offered safe keeping, or gave them safe passage onward to fortify other stories. And this was care-work, a craft even, with its own bruised grace inside a culture that could not be changed, a familial system that needed to be preserved for a kind of survival.

Later, I gathered pieces of information about the tongue. The rare books and documents smelt delicious, like old-growth forest—a rich earthiness rose from their pages. Others of vellum were salty in scent, soft to the touch and made no sound, the membrane silent when turned over. I thumbed metaphorical bodies: The Anatomy of the Soul, The Anatomy of Melancholy, The Anatomy of a Woman’s Tongue, The Anatomy of Abuses. I ran the tip of my index finger along the spines, letting the timer that controlled the light run down, shut off, working in half-light. No longer minding, no longer noticing.

The treatment of the tongue revealed cultures of violence and fear, and the organ required special thought and care in its use. But in the negotiation of this contested site, writings on the tongue also demonstrated, by virtue of their moralizing, how closely care and control could be interwoven.

The following spring I presented an extract at a seminar to share some initial findings on the historical treatment of the tongue.

Extract.

The organ itself is longitudinally separated into symmetrical right and left sides by a section of fibrous tissue, the lingual septum, that results in a groove or furrow on the tongue’s surface called the median sulcus. This is the line that scores the tongue through the middle.

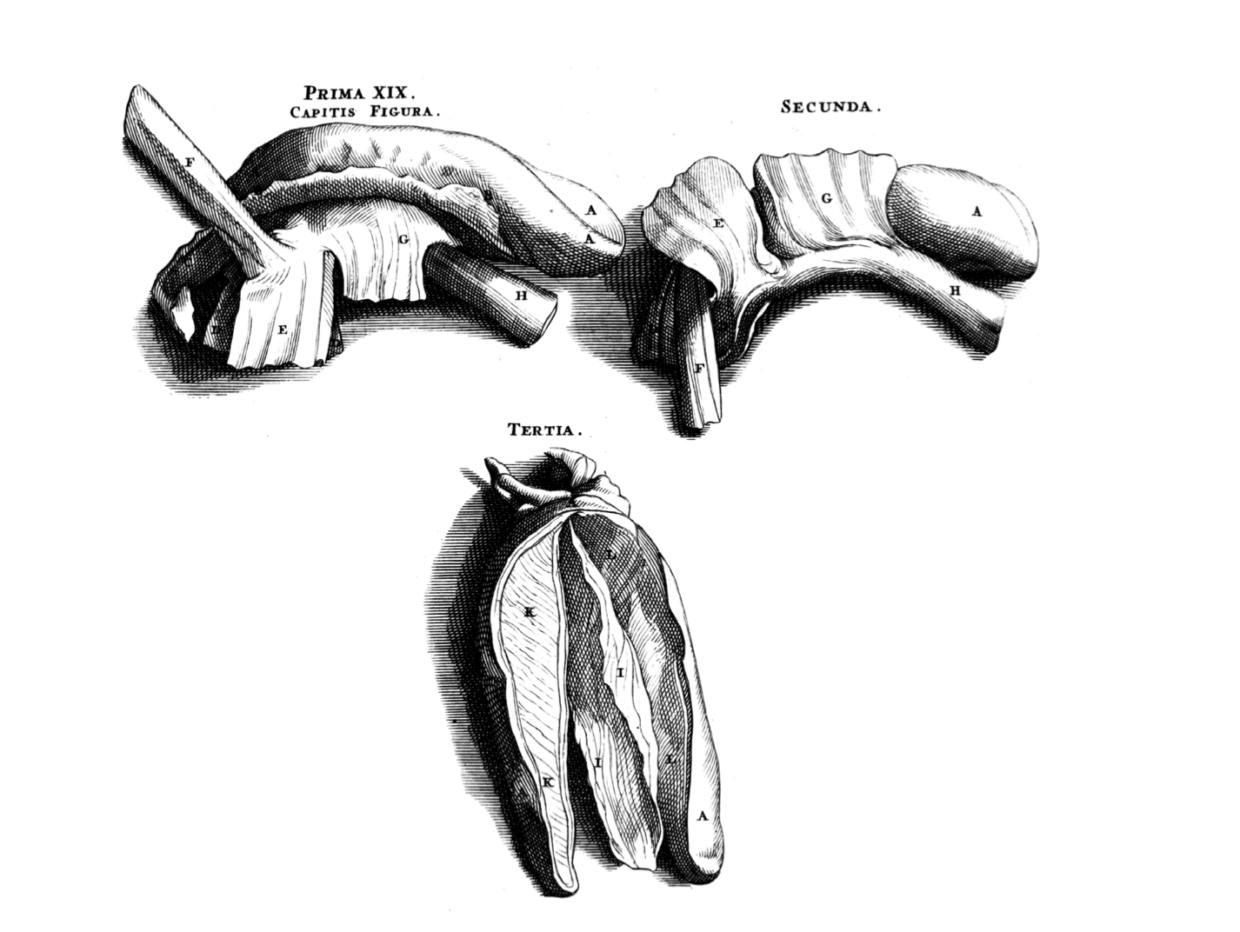

The philosophy of anatomy housed an assumption that the truth of a moral blueprint within could be excised – an old logic that married physiological markers with divine design. Moral topographies were written in sinew and bone. The view inside the tongue at its dividing line provided a glimpse of what stuff lay under the inscription at the surface. For moralists, the line evoked the anatomical duality of the flesh, and recalled an inherently deceitful organ. The tongue was mapped morally long before the organ was laid out on the slab, and it has been read and written over long after. My interests lie here, in the dissection. The sixteenth-century Belgian anatomist Andreas Vesalius made an incision down the median sulcus, butterflying the tongue, opening it out. The dissection revealed its shape when cut from the body, giving it a physical presence beyond its relationships with the palate, teeth, lips, and larynx or voice box. The tongue’s dual physiological landscape was examined where it cleaves, displayed according to the fissure.

Tongue | Language || Lingua

After the seminar a man who had made a comment disguised as a question approached me at the wine table. He was a historian by trade and had I read Latour? (I had not.) “Thank you for your question,” I said. We chatted for some time until I noticed the room had thinned out. He leant toward me and confided that he hears voices in the archive, the voices of the dead asking to be heard. Did I hear them too? “No,” I said. “I don’t hear voices exactly.” “What then?” he asked. “It’s more like the presence of things I can’t remember,” I said. Words rarely came to my aid like that and although what I’d said made little logical sense, he nodded as though it made sense to him. He was looking down, eyes on his empty glass. I asked him if he felt they were actual voices, the voices he heard. He nodded again and put his glass with the others. “Tell anyone and I’ll kill you,” he said.

It was very important to him, he explained, that his work in the academy was serious work. He was known in particular among his colleagues for the scientific rigor he brought to his field of historiography. I touched my left collar bone at the indent and found the strap of my bag slung there. I said I had to go. SALIVA! he cried suddenly, with an intensity that seemed both haphazard and precise. And he bubbled something about how spittle is a portal to the past. “All your ancestors back to the Neanderthals are contained inside your saliva!” he said, the room now empty but for the two of us.

The tongue had been made to wear its apparent proclivity for slipperiness and deceit (readings were made into its ecosystem and appearance). It was simply the best instrument we had for our projections. Interesting to consider, too, that words often have their genesis in the material. “Mendacity” comes from the Latin word mendax (lie) and has the root stem –mend, meaning “physical defect, fault.” This is also the source of the Sanskrit word minda, “physical blemish,” and the Old Irish mennar, “stain.” The lie carries these residues: a mark, a taint, the fleshly defect as sign. On another branch, the root stem -mend leads to “amend”—to free from faults, to set right, to make better.

Among the rows of boxes, with one bar of reception, my mother and I sent each other messages. I asked her about her day; I asked her questions about the past. She was often forthcoming, but equally often I felt like I was tipping a Magic Eight Ball upside down, shaking it, asking it to prophesy a pathway back instead of forward. I waited for her reply as though watching the triangle emerge from the watery murk with its abrupt, perplexing message.

Why did you make me lie about the violence?

No answer. It was not the right question. I tried a different one.

What, in your view, did my father lie about? She came online. She was typing… Everything.

And then she disappeared again, to last seen.

Different kinds of silence have their own idioms; they are passed down in family cultures. The wound on my father’s body concealed a tumor the size and shape of a fist. Deep in his abdomen it sprouted and metastasized until the evidence of its presence broke the surface, necessitating the line that divided his body into a right side and a left. That a text can be read allegorically does not make it an allegory. Allegory, by definition, contains instructions for its own interpretation.

I read my father’s body as confession. I traced words to their roots, I traced words for lying, for different kinds of lie in different languages. I believed if I went back far enough I could find understanding, or rather an answer would be there, waiting for me. Leaving the library after dark, walking past the rows towards the stairs at the end of the corridor, I saw my father, stapled crudely along his length, the drip drip drip of the saline solution, the riddle of him trying to work itself out of itself.

That a text can be read allegorically does not make it an allegory. Allegory, by definition, contains instructions for its own interpretation.Before this, during my first year of research, I became concerned that my interest in the tongue was devolving into obsession, even addiction, and I told Theo I would not be continuing. She just frowned and said nothing. The next time I saw her she pressed a copy of Augustine’s Confessions into my hand. “Who takes care of the past?” she said. Her words felt like a contract signed under duress. I laughed (fear; grief?). Until that point I hadn’t considered the past to be something that needed looking after.

In his essay A Plague of Mendacity, the Egyptian-American cultural critic Ihab Hassan wrote that lying may be a riddle deeper than language itself. It is wise to remember that the most adroit methods of innate deception have evolved for survival. Animal pretends to be plant, plant pretends to be animal. Mimicries of shape, color and scent saw some flowers outlive dinosaurs. In the temperate waters where I was raised, a crab decorates its carapace with algae and seaweeds to move undetected by predators. In the desert, a tongue orchid tricks a wasp into sex.

I met Theodora in a line waiting to hear Judith Butler speak on the topic of vulnerability. I held my place in the queue for an hour or so when it began to rain and my eyes fell on her back, on her sweater soaking up each droplet, until I could make out the spectres of two shoulder blades. She glanced back at me and smiled. I looked up and let the rain fall over my face. People ahead were being turned away at the door; the hall had filled to capacity. When this news filtered along the line a man behind me broke down at volume. I have thought often of him since, of his loud crying and how no one said a thing to him, how everybody left him there like he carried a taint, as though we might catch the thing that makes one reveal too much.

Etymologically, the lie contains residues of fault, but it is also the case that a truth can feel tainted, necessitating a lie. The truth of his need—of our need—felt marked, raw and vulgar the moment he stopped pretending he was fine. Saturated, I walked back to my attic room and thought about the Janus face of this problem, the messy truths we lie for, and the ways that those lies afford us a gritty shroud in less-than-ideal systems.

When I got home, I dried off and watched a YouTube clip of Butler talking about queer alliances. A queer alliance, they told a happily seated audience, is unpredictable and improvised, and might be a response to crisis. It is also, they said, a response to historical necessity. I would go back, see if he was okay—he might be gone, I thought—when there was the woman in the white sweater on the other side of my door. “I’m Theo,” she said. She was out of breath, and wet. She had followed me back and let herself in to the building.

I lived those college years in an attic with rising damp, listening to creatures moving in the walls, eating them out. The foundations of that place were rotted to the core. After Theo left I prepared coffee for a night of work ahead, and I read about protocols and devices used to enforce breakage. The bit and bridle had its inception in the British Isles in the Middle Ages. Records show it was principally used on those accused of gossiping, women who were thought to be outspoken or vying for power, or wives who moved beyond the boundaries of what their husbands and communities deemed suitable for them. The bridle held the head and face in iron and a two-inch rod was inserted into the mouth, clamping and flattening the tongue to prevent movement.

Learning by mouth was visceral. The bit and bridle would reshape the tongue, a technology that saw a violence upon the mouth-site designed to bring it into line and change the organ’s muscle memory. The device was repurposed for the long project of colonization, used to break the will of people taken to the Americas from their African homelands. What began with preventing speech was used as an index for the entire body. By going inside the mouth, body and mind could be silenced and reordered, reorienting a person towards another’s will.

I thought about what tongues are used for and what they can do, from the tip to the root. There is a habit of weakened use, a soft inheritance—a muscle trained in how not to move, how not to work. This habit may be rehearsed to non-use; rehearsed. The French naturalist Lamarck’s first law: more frequent and continuous use of any organ gradually strengthens, develops and enlarges that organ, and gives it a power proportional to the length of time it has been so used; while the permanent disuse of any organ imperceptibly weakens and deteriorates it, and progressively diminishes its functional capacity, until it finally disappears.

So, if a speaker stops using their tongue (not knowing why, or having chosen to stop using it, or having been violently forced to do so) over time eventually it seems like it was never meant to be used in that way. The idea here, the misbelief so pernicious and arresting, is that your tongue was never yours to use.

Theo helped me to remain present, remain focussed on what mattered. One night as we lay in bed she turned to me and smiled and touched her thumb to my cheek bone, my temple. “In the country where I grew up, we could be jailed for what we just did,” she said.

There are many ways to break a tongue, and there are many ways to recall its power, not only as an instrument of speech that shapes sound within its home of the mouth and palate, but as an organ involved in knowledge acquisition, sense making, flights and figment. In one 15th-century record from Europe, under the right moral and structural conditions, the tongue itself was believed to be a portal to hidden knowledge. The moon had to be in the right position, and the tongue and mouth needed to be washed clean, then certain precious stones placed under the tongue at the tie would allow visions of the future to be revealed. Ordinary people carried out the ritual. The organ was a threshold, a line or pathway bridging temporal and spiritual mysteries.

There are many ways to break a tongue, and there are many ways to recall its power, not only as an instrument of speech that shapes sound within its home of the mouth and palate, but as an organ involved in knowledge acquisition.What did those everyday folk feel or hear or see, I wondered? With all the parts in their right places, the precious stone under the tongue, and the moon up there on full. Those people believed in the tongue as a piece of psychic apparatus, as an organ that could bring fortunes to light. I spent a lot of time thinking about those people. I wondered, when everything aligned, if they saw the very day and moment they were in: where the past had brought them and where their future was being made. When what one had known, and what one would come to know, opened inward to unfold the present, imparting oneself to oneself like an actual miracle.

In the life of Saint Christina, her pagan father has her flesh torn off with hooks, her legs broken. Christina throws her flesh pieces at him: eat the flesh that you begot! The story spirals downward in this vein. He has her rocked in an iron cradle of hot oil and resin like a newborn babe. She is then paraded through the city naked with her head shaved, but when thrown in a furnace with snakes for five days they only lick the sweat off her skin. At the end of all this her tongue is cut out and, never losing her voice, she throws the severed thing at her tormentor, blinding him in the eye. Tongue flesh as pièce de resistance.

I assembled some pieces as instructed, gathering evidence for a confession I could not make or that I’d forgotten how to make or amend, make amends, make good, make it good, rehearse, rehearse—from rehersen, to give an account, to report, to tell, to narrate a story; to speak or write words; repeat, reiterate; from Old French rehercier, to go over again, repeat, literally to rake over, turn over soil or ground, to drag (on the ground), to be dragged along the ground; to harrow the land; rip, tear, wound; repeat, rehearse, from hearse: a framework hung over the dead. From herse, a harrow, from hirpus for wolf, in reference to its teeth (Oscan language, extinct). An avowal I held down like a job.

The night after I read The Tongue of Time, I dreamt that the scar on my father’s body was on my body. Waking to the taste of blood in my mouth, left incisor lodged on my tongue, a pain gradient revealed my jaw locked like a door. In the dream I am in the library trying to cram my organs back inside my body. I don’t have any staples, so I’m attempting to close the skin of my torso like a winter coat. This approach is reasonably effective but the experience of having my guts spill into my hands has been embarrassing.

I’m glad no one really visits this wing of the library. I hear the familiar turn of the timer and feel a thin light shiver through the gaps. When I reach the row and look at the dial it reads zero. I know that when I peer down there I will see a chair against the far wall with a box on it and although I want to pretend this is safe, if I walk down the row holding myself and reach the box I know the light will cut, in other words, a trap, and then I’m here.

________________________________

From the new issue of HEAT, Australia’s international literary magazine.

Since its inception in 1996, HEAT has been renowned for a dedication to quality and a commitment to publishing innovative and imaginative poetry, fiction, essays, criticism and hybrid forms. HEAT remains committed to featuring established voices alongside new ones, with the overarching aim of gathering literary perspectives that traverse geographic, cultural, and generational borders. With its minimalist, tactile aesthetic, Series 3 aims to throw light on a carefully curated selection of writers, inviting deeper focus and intellectual intimacy. Subscribe to follow the series as it grows and evolves, with each installment designed to be loved and preserved for years to come.