Nina Totenberg on Her Long Friendship with Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Her Loyalty, “Incredible Timing,” and More

In the years between by wedding and my widowhood, I became moderately famous—or to some, infamous—due in part to my reporting on Supreme Court nominees. Ruth Bader Ginsburg became truly famous as the second woman to sit on the Supreme Court. In an ironic twist, these parallel tracks helped nourish our friendship.

One reason was very basic: I understood her job. More than two decades of covering the federal court system had given me a special insight into the institutions where she worked, both the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, known primarily by its short-form name, the DC Circuit, and the Supreme Court. I had my own view of the pressures and challenges of the two courts and their dockets. And because it was my job, I was more than happy to talk about something else when I was off duty, as was she. But there was another aspect of this glide path to the spotlight.

Ruth and I knew each other long before other people were paying much attention to either of us. Much later, when Ruth became “The Notorious RBG” and everyone wanted a piece of her, that did not matter; we had decades of friendship between us already.

Two of Ruth’s greatest strengths as a friend were her loyalty and her incredible timing. The woman with a myriad of obligations and demands somehow made space for those she cared about at just the right moment. It was not simply her seminal advice or her invitations when Floyd was so ill. It was the other small acts of thoughtfulness, the things she did when no one was looking.

It took years before she loosened up with me.

In 1988, 110 years after its founding (and seven years after a woman was named to the Supreme Court), the Cosmos Club, a DC institution that prides itself on selecting members who are “distinguished in science, literature, the arts, a learned profession, or public service,” finally voted to admit women. One of Floyd’s friends belonged and wanted to nominate me. I wasn’t much interested in a social club, but Cokie and Linda insisted I do this, so against my better judgment, I agreed to be nominated as one of the first female members. As it turned out, I was blackballed. I have been told that a committee decides who to propose for membership, and one or possibly several members of the Cosmos committee privately voted no. I was really hurt to be voted down, and at some point, I told Ruth about it.

Unbeknownst to me, after my rejection Ruth was invited to visit the Cosmos Club, and at the end of the tour of its lovely interior, her escort asked her to become a member. Ruth demurred, and either then or later said, “You know, I think that a club that is too good for Nina Totenberg is too good for me, too.” It says everything about Ruth that she never told me about this; I heard the story from someone else. But she did fess up when I asked her about it. She was fiercely loyal without being self-aggrandizing, and not just to me. There were legions of such stories after she died. One of her former law clerks, Joe Palmore, remembered that when he went to work for the justice, he and his wife were struggling to find a good day-care situation for their one-year-old son. He told his fellow clerks, but as he recounted to his law partners at Morrison & Foerster nineteen years later, he “had no idea that the Justice knew, much less that she would try to fix the problem.”

As he later recounted, “One day, I accompanied the Justice to a speech at the Georgetown Law Center. Afterwards, we squeezed into an elevator with Court security officers and Georgetown personnel to depart. When the doors closed, the Justice asked, ‘Where is the daycare center?’ ” That indeed was Ruth, asking the central question and economical with her words.

Palmore continued, “Baffled, one of the Georgetown escorts said it was in the basement. The Justice answered, ‘I’d like to go there.’ So, we did. We got off the elevator, and the Justice led me and the rest of the entourage into the daycare center. At the front desk, she announced, ‘Hello, I’m Justice Ginsburg. My clerk Joe is looking for a daycare spot for his son, Simon. We’d like a tour.’ The Justice and I then navigated the blocks, toys, and toddlers to check out the daycare center. Together.” Problem solved.

I have to credit Ronald Reagan with being a proximal cause of some of the professional changes in both our lives. Ruth, however, credited Jimmy Carter. One moment came well into the 2010s, at a dinner party at my house. The usual suspects—Linda and her husband, Fred Wertheimer, Cokie and her husband, Steve Roberts, and Jamie Gorelick and her husband, Rich Waldhorn—were there. We somehow got on the topic of Carter, mostly lamenting his presidency and all the ways in which it had been a disappointment.

Ruth sat there, listening, and then raised her hand, straight up in the air. As all our eyes turned to her petite frame, she intoned, with a mischievous grin, “I dissent!” She then proceeded to praise the man who had brought her to Washington and who more than doubled the number of women on the federal bench.

It was, of course, Ronald Reagan who was the first president to appoint a woman to the Supreme Court. He campaigned on that promise and made good on it the first chance he got, naming Sandra Day O’Connor. It was also under Reagan that the Court began a gradual sea change to the right, one which continues and accelerates, no longer gradually, to this day. Ruth and I, in very different ways, were caught in the resulting waves and undertow.

Sandra Day O’Connor’s upbringing was the geographically polar opposite of Ruth’s. O’Connor was three years older; her parents owned and ran a 160,000-acre cattle ranch in Arizona, with no good school nearby. She spent her school years living with her austere grandmother in El Paso, returning to the ranch in the summer. In her autobiography, O’Connor described life on the ranch, including a great story about her being charged with bringing lunch to the ranchhands who were working with her father many miles away. At the time she was about thirteen, and as she drove across this untracked landscape, she got a flat tire. With no one to help, she changed it by herself, using her full body weight to jump on the jack. Needless to say, she was a bit late when she got to the roundup, but she was very proud of herself. Her father was not, telling her brusquely, “You’re late.” She explained that she had had a flat tire. To which he responded, “Next time, leave earlier.” RBG’s mother wasn’t so unforgiving, but her reaction to Ruth’s one poor grade on a report card contains the same undercurrent of greater expectations, a higher bar to meet, which both women internalized from beloved parents.

Precociously bright, O’Connor left to attend Stanford University at sixteen. She graduated third in her class from Stanford’s law school in 1952, at age twenty-two, one of only five women overall. (Future Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist graduated first.) Like Ruth, she made law review. O’Connor didn’t have an academic background, or experience in a law firm; none would hire her after her law school graduation, except as a secretary. She would serve in various public-sector jobs until she was elected to the Arizona state senate, where she rose to the position of majority leader before becoming a state trial and then midlevel appeals court judge. She was unanimously confirmed by the U.S. Senate in 1981 to replace the retiring Justice Potter Stewart.

I was thrilled when O’Connor was appointed, as were most of the women I knew. And the Reagan administration understood the importance of the first female justice. Her Senate confirmation hearings were the first to be televised for a nominee to the Supreme Court. What few of us could fully appreciate was the immense pressure and scrutiny she felt as the first woman. Along with batches of homemade fudge in her Court mail, she received notes that said, “Back to your kitchen and home female!” and “This is a job for a man and only he can make tough decisions.” Reporters dug through her trash and, paparazzi-like, chased her down at parties.

I never heard anyone discuss what Justices William Brennan or William Rehnquist wore, but the commentary on O’Connor’s wardrobe made it sound as if she moonlighted as a model for Vogue. Seven years in, the same year as my Cosmos Club debacle, legal journalist Stuart Taylor, writing about the relatively new Rehnquist-led Court in The New York Times Magazine, would sniff, “O’Connor in particular, whom Reagan seems to have chosen more for her sex than for her ideology.” No wonder she later said that she knew if she failed, women lawyers and judges across America, few as they were, would pay the price. Of course, she did not fail, and instead there was an enormous growth in the number of women judges, particularly at the state level.

Understandably, the experience made her guarded. Perhaps my least successful dinner party with any justice was when I invited O’Connor and her husband to my house not long after she was appointed. I got a good sense of the direction of the evening when she walked into my tiny kitchen as I was carving my standard leg of lamb, observed me with the knife for an instant, and then said, without preamble, “You’re cutting against the grain.” For a third couple that evening, I had invited lawyer Joseph Rauh and his wife, Olie. He was a well-known civil rights advocate who had been a military aide to General Douglas MacArthur in the South Pacific during World War II and had clerked for two distinguished Supreme Court justices, Benjamin Cardozo and Felix Frankfurter. I thought she’d be interested in him, but instead his presence seemed to irritate her.

We still saw each other socially and I did interview her, but it took years before she loosened up with me—some of that had to do with Ruth’s arrival on the Court, which took the burden of being the sole ambassador for a female judiciary off O’Connor’s shoulders. By the end of her tenure on the Court, some two decades later, she was stoically caring for her husband, who was living with Alzheimer’s disease. As his illness progressed, she would take him to her chambers for a few hours each day. “He would come and sit in her big office,” their son Jay recalled in an interview published in Forbes. “She had a couch. She would do her work, and he just sat there and looked through the newspaper. If he did wander off, it would be harmless, because there always would be a guard nearby.”

O’Connor announced her retirement from the Court in 2005 to care for him, but Chief Justice Rehnquist’s death kept her on the bench until January 31, 2006, six months later. By then, as O’Connor biographer Evan Thomas noted, John O’Connor “could barely recognize” his wife of nearly fifty-five years, and she soon regretted her decision to step down. She was a vigorous seventyfive when she left, youthful by the standards of the recent Court. O’Connor also could no longer properly care for her husband and had to move him into a care facility in Phoenix. There he grew interested in another woman. As Thomas wrote, Sandra Day O’Connor, less than a year after ending her service on the highest court in the land, “would come in and find her husband holding hands with this other woman, and with her characteristic strength she would sit down and take her husband’s other hand.”

I saw her not long after that. We were both featured at a November 2007 conference called The Presidency and the Court, held at Franklin Roosevelt’s Presidential Library. I was moderating several panels and presenting, and Sandra was the keynote speaker. Having been a caregiver myself for so long, I could see the strain and exhaustion written across her face. She had recently broken her foot and was wearing clunky orthopedic shoes. As the conference’s, concluding dinner dragged on, Sandra, seated next to me, turned and asked in a low voice, “Do you think I could leave early?” “Absolutely,” I said. “You look so tired. Go!”

Not long afterwards, I would be saying something similar to Ruth, who until almost the end of Marty’s life, was his sole caregiver.

__________________________________

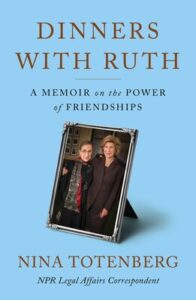

Excerpted from Dinners with Ruth: A Memoir on the Power of Friendships by Nina Totenberg, available via Simon & Schuster.

Nina Totenberg

Nina Totenberg is NPR’s award-winning legal affairs correspondent. She appears on NPR’s critically acclaimed news magazines All Things Considered, Morning Edition, and Weekend Edition, and on NPR podcasts, including The NPR Politics Podcast and its series, The Docket. Totenberg’s Supreme Court and legal coverage has won her every major journalism award in broadcasting. Recognized seven times by the American Bar Association for continued excellence in legal reporting, she has received more than two dozen honorary degrees. A frequent TV contributor, she writes for major newspapers, magazines, and law reviews.