Nikita Lalwani on the Art of Eavesdropping

"I urge my writing students to eavesdrop."

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Like many writers, I eavesdrop as a matter of course. In London, if I am taking the subway home after a night out, round midnight, I have found myself on the platform studying the people around me. Very occasionally, I have moved to join a carriage that contains people who look interesting. At this time, it is usually a couple of some sort who have the most draw; whether amorous, awkward or indifferent, the elastic band between two people in a relationship will generally keep my attention.

It doesn’t mean I walk home from the station with glinting gems of invaded privacy in my pocket; usually I just get a sense of a mood, punctuated with unmemorable dialogue. It’s an ephemeral experience. But at the time, I must confess, it is consuming. With my own novels, I have found that it is close observation that introduces surprise into the text, and that steers me away from cliche.

I urge my writing students to eavesdrop, and to ride the wave of delicious trespass that is at the heart of the word itself (in the 17th-century version, it indicated a person who listens from under the eaves of a house, to check occupancy for hopeful burglars, although there are earlier meanings as well). New students look a little alarmed at this point, which I can understand. It leads to an uneasy, useful discussion about the ethics of writing from life, whether one’s own or those of others.

I reassure them that I am talking about eavesdropping as part of the precise observational craft that is writing, the commitment that writers make to watch and listen, becoming Isherwood’s walking lens—”I am a camera, my shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking,” he wrote in Goodbye to Berlin. Become the camera, make it a habit, I say. Get into the habit of looking for detail, whether verbal or non-verbal, intimate or inanimate. Notice it. Record it. Over and over again. Once you start writing, immersing in the mish-mash of then and now, you’ll find that it all turns into the mud of your book. You can worry about the ethics later, if necessary. Your focus right now, is truth.

Most novels contain more than one character and cannot be sustained solely by the author’s own lived experience. The lone protagonist in Hunger by Knut Hamsun is tortured by the absence of company. Writing fiction will always require walking in shoes that do not belong to you. The only option is to try and do it well, without insult. For that, we need to care enough to listen.

__________________________________

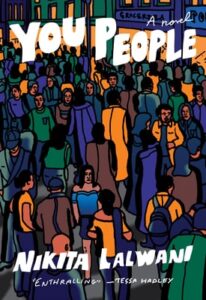

You People by Nikita Lalwani is available via McSweeney’s.

Nikita Lalwani

is a contemporary British novelist whose work has been translated into sixteen languages. Her most recent novel, You People, was published by McSweeney's in 2021. Her first novel, Gifted, was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award, and won the Nikita Lalwani is an inaugural Desmond Elliott Prize for Fiction. Her second, The Village, was modeled on a real-life “prison village” in northern India, and won a Jerwood Fiction Uncovered Prize. Nikita wrote the opening essay for AIDS Sutra, an anthology exploring the lives of people living with HIV/AIDS in India and is a trustee of the Civil Liberties Trust, a human rights organization.