Naw thep’thay’gaw: On Telling a Multicultural Indigenous Story

Oscar Hokeah’s Chronicle of Kiowa and Cherokee Life

My father immigrated to Oklahoma from Aldama, Chihuahua, Mexico when he was only 14 years old, following his older cousins to work the peanut and cotton fields on the Southern Plains. My mother is a full blood Native American, half Kiowa and half Cherokee, and she raised me as a single mother between her two tribes. Growing up in this intertribal and multicultural atmosphere, I went from traditional dances with Kiowas and Comanches to traditional dances with Cherokees and Creeks.

I have vivid memories of living in old farmhouses with groups of migrant Mexican workers, who spent their days working the red earth of the Southern Plains under the grueling heat of an Oklahoma sun. As I grew into adulthood I came to terms with the various identities informing who I am. Not just my cultural identity, but my shifting identity as a man, and how the Indigenous matriarchs around me informed who I was as a male in my tribal communities.

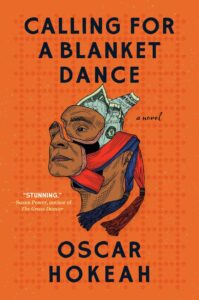

When I wrote my first novel, it became about all this: about family, naw thep’thay’gaw, and how families show up for each other. The title—Calling for a Blanket Dance—comes from an important ritual in powwow culture. It’s a communal effort in supporting tribal members, where someone carries a Pendleton blanket into the arena, lays it out in front of the drum, and they make an announcement to everyone at the powwow, letting the community know that there’s someone in need.

The individual in need stands next to the blanket and the drummers will start a song. During the course of the song, dancers and spectators alike will enter the arena and drop crumpled dollar bills onto the blanket. It’s a gift—as much an act of kindness as an act of communal healing. After the drummers finish singing the powwow song, the person who made the announcement will gather up all the money off the blanket and ritually hand the money to the individual in need. When we call for a blanket dance, we’re asking for the community to help lift someone up during one of their darkest moments.

Like my main character, Ever Geimausaddle, I came to understand the multifarious nature of my own identity through my family. As I mentioned above, I’m Kiowa, Cherokee, and Mexican. I knew firsthand the back and forth sway between traditional Indigenous values and an out-of-control patriarchy. I always tell people that I was raised with three mothers: my biological mother, Virgilene Hokeah, her sister, Linda Hokeah-Tahsequah, and my best friend’s mother, Linda Phillips. At the time, I didn’t understand this was a traditional Indigenous practice. It was just the way we all lived. Sisters parented each other’s children. This meant that my cousins were my siblings, and my best friend and his siblings were also my siblings.

I wanted to show a dynamic of the Native American world very few consider and also give readers a slice of America very few know about.

When a Native person tells you that someone is their sister or brother, they might not be biological siblings but since we live in such a tightly knit structure we view each other as such, and we are obligated to each other emotionally and spiritually to the same degree. Because of these very strong Indigenous values, I personally had a way out of the traps of living in poverty, which often comes with cruel options like addiction, prison, and violence.

In addition to exploring the subtle and obvious ways male-on-male violence permeates a working class environment, I also wanted to disrupt the homogenous perception of Native Americans. Because I grew up between Kiowa and Cherokee tribes, I lived the beautiful differences of each. Oklahoma is host to 39 different tribes. Each has its own language, practices, customs, and rituals. There are shared practices that bind us together and we also share the scars of a brutal colonial history. This history unites all tribes throughout the Americas. What I felt was missing was acknowledgement of the differences among us.

Sometimes this manifests in intertribal conflicts, but more often than not this is the medicine that creates multicultural tribalism, where we exchange and share and gift each other practices and ideologies, such as gourd dance rituals between Kiowa and Comanche and matrilineal customs between Cherokee and Creek. The outcome is a richness in tribal cultures. In juxtaposing Kiowa and Cherokee communities, I wanted to show a dynamic of the Native American world very few consider and also give readers a slice of America very few know about.

Juxtaposing two tribes is easier said than done. Initially, it was easy to distinguish the differences. I knew the difference in languages, rituals, and landscapes. Kiowas were on the Southern Plains. Cherokees were in the Ozark Hills. Kiowas practiced the Gourd Dance, while Cherokees practiced the Stomp Dance. But if that were the extent of it, then this novel would’ve been completed back in 2008 when I wrote one of its earliest chapters. The element that was most difficult to capture was voice.

Our desires and identities shaped by those who love us the hardest, who pick up the edges of the blanket in our honor.

At an early stage in our development as writers we struggle with voice. It’s super elusive. We can name it and see it in our favorite authors. But ask us to develop it and we find ourselves in a depth of mental torment for sometimes years, if not decades. I knew I needed to distinguish the difference between Kiowa community members and Cherokee. How was I going to accomplish this task when I couldn’t even hear my own accent?

Attending the BFA Program in Creative Writing at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, I traveled back and forth between New Mexico and Oklahoma, and I frequently traveled between two different accents. Once I could distinguish the difference between a New Mexican accent and an Oklahoman accent, I then began to hear the difference between Tahlequah and Lawton, and then between Cherokee and Kiowa. I’m not one for talking. I’m more of a listener. I’m good at one-on-one conversations. Because of this trait, I started to pick up on subtle pauses and phrases. After years of listening and contemplating, I finally had a distinctive Kiowa voice and a distinctive Cherokee voice that effectively juxtaposed these two different tribes.

Ever Geimausaddle was born out of a desire to show readers how Native families are tightly knit, and how we solidify bonds through rituals that connect extended family—our cousins are our siblings and our aunts are our mothers—so traditional kinship customs are alive and well in our communities. In a rapidly shrinking world, Natives, like everyone else, are modern constructs of a global community. And so Ever has no boundaries. He is as much Kiowa as he is Cherokee as he is Mexican. He is pulled in numerous directions and pushes back with the ferocity of his ancestors. Ever destroys walls built by metal and emotion. And isn’t this the universal human condition? Our desires and identities shaped by those who love us the hardest, who pick up the edges of the blanket in our honor, but ultimately, by our will to make the future our own.

__________________________________

Calling for a Blanket Dance by Oscar Hokeah is available via Algonquin Books.

Oscar Hokeah

Oscar Hokeah is a citizen of Cherokee Nation and the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma from his mother's side and has Latinx heritage through his father. He holds an MA in English with a concentration in Native American Literature from the University of Oklahoma, as well as a BFA in Creative Writing from the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), with a minor in Indigenous Liberal Studies. He is a recipient of the Truman Capote Scholarship Award through IAIA and is also a winner of the Native Writer Award through the Taos Summer Writers Conference. His short stories have been published in South Dakota Review, American Short Fiction, Yellow Medicine Review, Surreal South, and Red Ink Magazine. He works with Indian Child Welfare in Tahlequah.