Natural Alchemy: On the Long History of Community Gardens in Indianapolis

Angela Herrmann Considers Urban Agriculture and Food Production

“Urban planners and agricultural experts predict that there will be no farmland remaining in [Marion County] by the year 2050.”

–William D. Dalton, The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis

*Article continues after advertisement

The 2020 gardening season began in late January, much like it has each year for the past two decades, with a few messages back and forth among gardeners with offers of catalog and seed exchanges and attempts to schedule a time to meet and organize ourselves for the upcoming season. As one of the original members of the Rocky Ripple Burkhart Community Garden, established in 2001, our routine has evolved from email messages (and a short-lived newsletter) to a now-defunct Yahoo group, to a now-active Facebook group.

But by mid-March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had nearly shuttered the entire city of Indianapolis except for those businesses and services deemed essential. Nevertheless, we were quick to establish that a community garden is essential, as long as those working in the garden followed masking and social distancing guidelines.

That’s the alchemy of community gardens. No matter what life throws at Hoosiers, such as war, economic uncertainty, social inequality, energy shortages, insect pests, or even a pandemic, community gardens always will be essential. Even while social distancing, gardeners will transform a piece of land into a vibrant oasis of community, food, and flowers. Rocky Ripple’s community gardeners are part of a rich tradition of Indianapolis residents who have grown food in the city.

Indeed, people have always grown food in or near cities. For instance, in the 1850s, “prior to refrigerated transport, New York City supplied all its food for a population of over a million from within seven miles of the borders of the city.” Community gardens have been an integral part of US urban food production with their historical roots emerging from England’s allotment movement in response to urbanization and industrialization in the late 1700s and 1800s.

The Roots of Urban Food in Indianapolis

Food production has always been a critical component of Indiana’s economy. Indiana established the State Board of Agriculture in 1851 to promote “modern” farming. The first Indiana State Fair was held in 1852 to promote agriculture throughout the state. And in 1862, Congress passed the Morrill Act, which established a nationwide chain of land grant colleges and universities to teach agricultural and mechanical arts—the Extension Program. Purdue University, Indiana’s land grant school, was founded in 1869 to help farmers learn new methods, adopt new technologies, and increase production. Little did they know that Purdue University Extension would later become a vital partner to Indianapolis’s urban growers with the same objectives!

Indianapolis’s earliest pioneer and immigrant farmers took advantage of central Indiana’s alluvial soils, enriched by the White River and its tributaries. On higher ground, directly across the river from Rocky Ripple, long before Rocky Ripple was incorporated and long before Crows Nest became one of Indianapolis’s poshest neighborhoods, the Lemings were one of the families who farmed the area. Tombstones for my fourth great-grandparents, Indiana pioneers James and Nancy (Thomas) Hubbartt and other Hubbartt relatives, are located on what was once Leming land.

James had farmed near Broad Ripple and near Crooked Creek east of Michigan Road. Better known are the German immigrant farmers who arrived in Indianapolis by the mid-1800s. You might recognize some of these names: Brehob, Nordholt, Hohlt, and Heidenreich. They provided fresh fruits and vegetables for more than 15,000 Civil War soldiers in Indianapolis (perhaps James Hubbartt’s son and my third great grandfather George were among them?). They organized themselves as the Deutscher Gartner Unterstützungs Verein zu Indianapolis or Farmers Benefit Society of Indianapolis in 1867. These immigrant farmers sold their produce at the original Indianapolis City Market, an open-air structure from the 1830s through the mid-1880s. The current Indianapolis City Market opened in 1886 and served farmers from within and around the city.

In 1920, the Marion County Greenhouse Growers Association formed to promote uniform growth of produce. According to Dawn Mitchell in her Indianapolis Star article “Retro Indy: The Greenhouse Growers,” by the 1940s, “… the south side—most notably along Bluff Road—had the highest concentration of greenhouses in the United States with 80 to 85 growers owning nearly 40 acres each.”

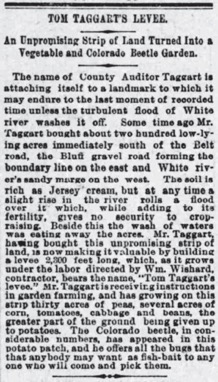

Of course, if you know the topography of Indianapolis, with the exception of Crows Nest, flooding has always been a concern. Rocky Ripple gardeners have always been acutely aware of this possibility, but they’re not the only ones, as this newspaper article about Tom Taggart’s levee from the May 24, 1891, issue of the Indianapolis Journal attests.

Urban Food Supports War Efforts

While many Hoosiers aspired to get off the farm and into the city, it seems that the farm never really left Indianapolis residents. The farms that weren’t developed or paved over, the city simply grew around them. Larger scale food production evolved with the times, and yet backyard and community gardens became essential to the WWI and WWII efforts. Urban food production meant transportation resources could be conserved to support the war.

WWI War Gardens

So many Indianapolis residents participated in War Gardens that Indiana became home to one of the largest state campaigns of the National War Garden Commission. Not surprisingly, a Purdue University lecturer coordinated that effort. Indianapolis banks and businesses helped distribute the “Food Garden Primer” for the benefit of those who did not have growing experience.

Gardeners will transform a piece of land into a vibrant oasis of community, food, and flowers.

“The women of Indiana surely have a big campaign mapped out and the national war garden commission will be very glad to help them in every way… For Indianapolis alone we have sent 10,000 of our primers to… the Patriotic Gardeners Association,” according to a report appearing in the March 8, 1918, issue of the Indianapolis News. Even the real estate industry promoted the effort. 1920s advertisements promoted homeownership as a means of owning a war garden.

WWII Victory Gardens

Within a generation, gardens were again essential to wartime efforts, such that rationing of canned food required everyone to participate in food production. The 1943 Victory Garden program called for four types of gardens: farm gardens, city home gardens, school gardens, and community gardens. In 1943 alone, Marion County’s Victory Gardens produced 40 percent of all vegetables grown. Even Indianapolis’s Jewish Post promoted more participation in the effort and encouraged a 15 percent increase in production.

Post-War Food Production

As post-war prosperity pushed food production away from cities, including Indianapolis, grocers rather than gardeners emerged as key food providers. While expendable income grew for many, not everyone shared in the postwar prosperity. Thus, projects like the Flanner House Urban Farm helped address high costs and food insecurity for African American residents.

Albert A. Moore, director of agriculture, launched urban farming efforts at Flanner House in 1946 after having served in Camp Atterbury in WWII. Flanner House launched a cannery in 1947 to address increased food prices and shortages. The cannery and gardens were originally located at 812 N. West Street. According to the Indiana Historical Society, the Flanner House community tended some 600 community garden plots. At the same time, members trained to can produce and sell staples at a co-op grocery store.

Community Gardens and Urban Food Production: Responses to Hunger

Community gardening regained its popularity in the United States again during the late 1960s through the 1980s, during the Vietnam conflict, and following the 1979 oil crisis. A pattern suggests that community gardening and urban farming activities have tended to increase during periods of war or social uncertainty. When the economy contracts, people rely on gardening as a way to stretch their food budgets.

Mayor’s Garden Project

The Mayor’s Garden Project, organized under the administration of Mayor Richard Lugar on April 5, 1975, was launched in response to rising food prices. Lugar saw the value in urban gardening when he learned that “a person farming a 15-by-18-foot lot could raise $100 worth of food during the summer.” According to the inflation calculator, that translates to about $476.57 today.

The first garden, created to aid poor and older adults, was located on land at Central State Hospital. The city leased plots for $5 ($1 for senior citizens), and provided six kinds of seeds and tomato plants, along with horticultural advice. Inner-city residents were given access to garden plots to rent. Because of the popularity of the program, with 3,000 people signing up for the project within two weeks, more land was added to the project, including 20 acres in the 2400 block of north Tibbs on Indianapolis’s west side.

Phyllis Hackett, former president of Riverside Neighborhood, Inc. and former planner for Community Action Against Poverty (C.A.A.P.) in the 1970s, said city employee Mary Oldham “garnered the idea” of a city-wide gardening program. Hackett took the idea to a city director who allowed her to organize a C.A.A.P. neighborhood gardening program, which she said contributed to the launching of the Mayor’s Garden Project (Hackett). Gleaners Food Bank was another outcome of C.A.A.P. (later renamed Community Action of Greater Indianapolis). Gleaners incorporated in 1980, expanding from Marion County to serve the state of Indiana, creating one of the nation’s first affiliate food bank networks.

Capital City Garden Project

In 1985, Indianapolis became the site of one of 23 urban gardening programs funded by the US Department of Agriculture. The Indianapolis program was administered by the Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service in Marion County as the Capital City Garden Project. The Capital City Garden Project’s mission was to be a community-based educational program in Marion County, promoting healthy people and greener neighborhoods through gardening. The project provided neighborhood groups and backyard gardeners the basics of urban food production and neighborhood beautification. The CCGP, once affiliated with the American Community Garden Association, has now been rolled into other Extension programming.

City-Wide Garden Projects

In the late 1980s to early 1990s, Purdue Extension began establishing gardening projects at public housing sites and inner-city neighborhoods in Indianapolis. Roots of Ruckle, which was located in the Mapleton Fall Creek neighborhood, was among the first. In 1990, longtime Beechwood Gardens resident Essie Rowley, along with her neighbors, brought the nationwide project, End World Hunger Community Food Garden Club, to her eastside low-income public housing complex as a means of reducing hunger, eliminating crime, and improving residents’ health.

Rowley started the only community garden and the first food pantry in Indianapolis public housing with support from the Capital City Garden Project. Consequently, she was recognized in 1993 with the Mayor’s Volunteer Partnership Award by then-mayor Stephen Goldsmith. John Shaughnessy documented her efforts in The Indianapolis Star, “Public Housing Matron Never Gives up Despite Life’s Downs,” October 8, 1993.

Indy’s Community Gardens

When Tom Tyler began his work at Purdue Extension in 1988, community gardens happened mostly in public housing or near economically depressed areas. Tyler said he wanted to promote the idea that community gardens could be as diverse as those planting them: from a couple of people planting flowers, to large public garden plots and youth programs.

Indeed, community gardens seemed to sprout all over Indianapolis, at schools, churches, the Indianapolis Children’s Museum, the governor’s residence, Washington Park North Cemetery, and the Indiana Women’s Prison. Tyler and his staff developed partnerships with the Marion County Health Department, schools, Indy Parks, community centers, the Knights of Columbus, Indianapolis Downtown, Inc., the Junior League, and Keep Indianapolis Beautiful to develop and promote community gardens. One outcome was the partnership between the Junior League and the Extension office to produce the publication Neighborhood Harvest Building Community Gardens in Indianapolis.

When the economy contracts, people rely on gardening as a way to stretch their food budgets.

In 1997, when Governor Frank O’Bannon and his wife Judy moved into the governor’s residence, First Lady O’Bannon immediately opened the residence gardens to the public, referring to them as an extension of the “state’s living room.” In an interview with Mrs. O’Bannon, she said that when she and her husband lived on the Old Northside, they lived between two Housing and Urban Development (HUD) houses and among about 50 [neighborhood] kids.

So, as Mrs. O’Bannon had done all of her life (growing up helping her mother in a Victory Garden), she “started digging around that lot, and soon the children began to come out, curious to see what she was doing. Shortly after the parents followed and before long, people who barely knew each other began getting to know each other and building trust.”

When the O’Bannons moved into the governor’s residence, she continued promoting community gardening. When the ACGA national meeting came to Indianapolis in 1997, Mrs. O’Bannon served as the keynote speaker to some 300 attendees who also toured Indianapolis-area gardens.

The concept of food security became part of the Indianapolis community gardening landscape since many gardening projects emerged in response to limited access to fresh produce, high food prices, and hunger. In 1997 the Extension office partnered with Gleaners Food Bank and Americorps to develop a community food security coalition to create a foundation for increasing food access in what we now know as food deserts.

The Future of Food is in the City

That brings us to 2000, when Nancy Barton, Sue Gilfoy, and others began conversations around the launch of a community garden in Rocky Ripple’s Hohlt Park, on a site named in honor of market farmer Rick Burkhart who once owned the parcel of land on which the community garden is now located. The garden began its first season in 2001 and has enjoyed support from Purdue Extension and Keep Indianapolis Beautiful. It has been continuously active every year since.

And while it’s a relative newcomer in the city’s urban agriculture efforts, nothing has changed. Gardener interest waxes and wanes depending on social pressures. Heavy precipitation events leave gardeners worried if this will be the year of the next big flood. And this year, for whatever reason, the Colorado beetles have staked a claim to the potato patches in several gardener plots, mine included. New this year is the pandemic, but that didn’t stop Indianapolis-area gardeners from getting outside. Indeed, during a time of enforced quarantines, the community garden is the one place where we’re never alone.

Meanwhile, a host of Indianapolis’s young urban farmers now produce food to sell at markets and to restaurants—Matthew Jose and Amy Matthews have moved their farm to the Bluff Road area to rejuvenate one of the old German farmsteads along Bluff Road. To this day, gardeners continue to work the soil at the Mayor’s Garden Plots on Tibbs. Flanner House, now located at 24th & Martin Luther King Street, continues its agricultural traditions to create one of the city’s largest urban farms in the middle of a food desert.

Albert Moore’s descendent family members are carrying on the urban ag tradition in Mapleton Fall Creek. And now new communities of Burmese immigrants are establishing their roots in Indianapolis with new community gardens on the north and south sides of Indianapolis. At this rate, I’m confident that Indianapolis residents will continue gardening, and farming, in Marion County well into the future!

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Indianapolis Anthology, edited by Norman Minnick. Used with the permission of the publisher, Belt Publishing. Copyright © 2021 by Angela Herrmann.

Angela Herrmann

Angela Herrmann is an Indiana-born writer, photographer, and gardener. She is a silver-level Advanced Master Gardener and has earned certificates in agroecology and permaculture.