Nancy Mitford, Inventor of Eccentric English Style

On the (Very) Strong Fashion Opinions of a British Icon

Nancy Mitford was one of the Bright Young Things—a carefree gang of upper-class creatures who partied and shrieked their way through 1920s London. “We hardly ever saw the light of day, except at dawn; there was a costume party every night: The White Party, The Circus Party, The Boat Party,” she affirmed in 1966, according to a biography of her, Life in a Cold Climate. The Bright Young Things’ lives and loves were captured by one of her best friends, Evelyn Waugh, in his novel Vile Bodies, and to many, the larks and frolics of this group of aristocrats were a discordant hum in the background of postwar routine.

The Mitford style has become code for an “eccentric English” way of dressing—understood both by those fueled by fashion and those without insider intelligence. It means thick wool cardigans and stout walking shoes, wellingtons worn with silk ball dresses and fur tippets, and tweedy coats thrown over floral tea dresses. When living in England, Mitford habitually wore velvet suit jackets and wool skirts in town, and tweeds and shaped, darted blouses in the country, accessorized with sturdy brooches, a china-white complexion, threadlike eyebrows, and lustrous pearls. Ironically for a clotheshorse known for quirky British flair, Mitford spent her life disparaging the way English ladies dressed, and she insisted in her 1963 collection of essays, The Water Beetle, that the suits they wore were “deplorable, they are of tweed thick and hard as a board, in various shades of porridge.” For society’s in crowd, “nothing was considered as common as to be dressed in the height of fashion.”

In her essay “Chic-English, French and American,” published in 1951 in Harper’s Bazaar, she contended that the British woman’s wardrobe rested on “a contempt of the current mode and a limitless self-assurance.” She decried what was to her the almost intrinsic, fundamentally bad dress sense of English women. “I saw Rosamond. . . Oh the dowdiness of English women—has it always been the same or are they worse now—I can’t remember. It is so fundamental that I suspect the former. The London New Look made me die of laughing—literal chintz crinolines. Apparently Dior went over et lorsqu’il a réfléchi que c’est lui qui a lancé tout ca il était pret a se suicider [and when he realized it was he who had started it all, he was ready to commit suicide].”

For Mitford, Paris was fashion nirvana. Her first couture dress was from Madam Gres, a French house that the New York Times called, in the 193os, “the most intellectual place in Europe to buy clothes.” The gown was made from black velvet with a chiffon waistband, and cost £200. However, it was Christian Dior’s clothes that she fell hard in love with. When his 1947 collection hit the catwalk, she wrote to her sister, Diana, in England: “Have you heard about the New Look? You pad your hips and squeeze your waist and skirts are to the ankle. It is bliss.” She hurried to get fitted and revealed: “I stood at Dior for two hours while they moulded me with great wadges of cotton wool and built a coat over the result. I look exactly like Queen Mary. Think how warm though. . . All the English newspapers are on to the long skirts and sneer. But all I can think is now one will be able to have knickers over the knee.”

In 1945’s The Pursuit of Love, she writes of her heroine: “Linda had one particularly ravishing ball-dress made of masses of pale grey tulle down to her feet . . . and made a sensation whenever she appeared in her yards of tulle, very much disapproved of by Uncle Matthew, on the grounds that he had known three women burnt to death in tulle ball dresses.” Humor is a thread that runs through all of Mitford’s fiction. She was untrained and largely uneducated, apart from learning to write and speak French as a girl, but she nevertheless had a confidence that animated her writing with a voice that rang true. The worlds she wrote about fascinate the outsider; she gave a rare glimpse of what exactly went on in the drawing room.

Her first-ever article in American Vogue in 1929 was titled “The English Shooting Party,” and it reveals the mysteries of a blue-blood weekend in the country. She advises: “Wear a little coat over your dinner-dress; chattering teeth and goose flesh do not add very materially to the feeling of good cheer that is supposed to pervade the dinner table the first evening and there are few houses where it is good form to rise during dinner and beat the breast in order to stimulate circulation and enthusiasm.”

__________________________________

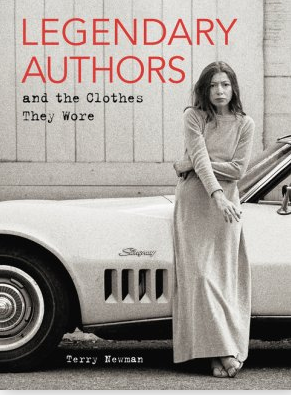

From LEGENDARY AUTHORS AND THE CLOTHES THEY WORE by Terry Newman. Copyright © 2017 by Terry Newman. Reprinted courtesy of Harper Design, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.