Namwali Serpell on Toni Morrison and the Power of Ambiguity

"Beloved reflects a deep ambivalence about revelation, specifically about the use of language to reveal."

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

In an important 1987 essay, “The Site of Memory,” Morrison described how a double bind distorted the original slave narratives:

Over and over, the writers pull the narrative up short with a phrase such as, “But let us drop a veil over these proceedings too terrible to relate.” In shaping the experience to make it palatable to those who were in a position to alleviate it, they were silent about many things, and they “forgot” many other things. . . . For me—a writer in the last quarter of the twentieth century, not much more than a hundred years after Emancipation, a writer who is black and a woman—the exercise is very different. My job becomes how to rip that veil drawn over “proceedings too terrible to relate.”

The earliest depictions of slavery were already crawling with the terrible proceedings the Gothic tends to depict, from bloody whippings to family curses to the wrathful wraiths of the slain enslaved. Morrison here isolates a trope of the genre that many slave narratives—and later works of black literature—used metaphorically: the veil, which sits etymologically at the center of the re-vel-ations that disclose scenes of horror.

But Morrison knew she could not just pull back that veil and shock us with the atrocities behind it. In an essay about writing Beloved, she explained: “The problem is always pornography. It’s very easy to write about something like that and find yourself in the position of a voyeur, where actually the violence, the grotesqueries and the pain and the suffering, becomes its own excuse for reading. And there’s a kind of relish in the observation of the suffering of another.”

Nor could she simply speak what has been unspoken, or give voice to the voiceless, efforts for which she is often reductively lauded. This is the paradox Audre Lorde articulated in her essay “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” How can you use the very language that has been used to silence and oppress you? For all these reasons, Morrison maintains in her foreword, “To render enslavement as a personal experience, language must get out of the way.” But how can language get out of the way . . . in a novel?

This is why the form of Beloved—famously difficult, almost willfully obscure—reflects a deep ambivalence about revelation, specifically about the use of language to reveal. Morrison has to redress the concealing and conciliatory language of the slave narratives. But she also has to avoid the dangers language as such posed to the enslaved: the inscriptive violence wielded by the law and pseudoscience, as well as the spectacle of black suffering that rode the line between flattering the audience’s prurience and its prudery. As she says of writing about historical facts of slavery such as the “bit” in the mouths of the enslaved: “I wanted it to remain indescribable but not unknown.”

This is where literature, Morrison’s chosen form, can do something that other kinds of discourse cannot. Unlike authoritative declarations of truth, fiction has no obligation to dispel ambiguity. It can make use of it—even intensify it—in order to evoke and transform experience. In Beloved, Morrison does take possession of the master’s tools, but she bends them, breaks them, and then uses them to reshape the house.

In this way, she defamiliarizes slavery, in Viktor Shklovsky’s terms. “The purpose of art,” this Russian Formalist wrote in 1917, “is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception.”

Making the objects of slavery “unfamiliar,” and her literary forms “difficult,” Morrison imparts not how slavery came to be known in standard or official narratives, but how it was sensed and perceived by the enslaved themselves. And she does so not simply by writing a work of black Gothic fiction, but by infusing its tropes—the veil, possession, the undead, the familiar—into the very form of the novel, such that they govern its style, story world, and structure. The haunt becomes an aesthetic principle.

_________________________________________

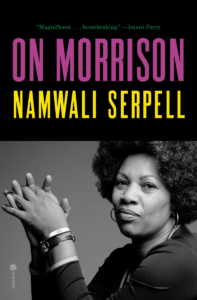

From the book ON MORRISON by Namwali Serpell. Copyright © 2026 by Namwali Serpell. Published by Hogarth, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Namwali Serpell

Namwali Serpell is a Zambian writer who teaches at the University of California, Berkeley. She won the 2015 Caine Prize for African Writing, received a 2011 Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, and was selected for the Africa39, a 2014 Hay Festival project to identify the most promising African writers under forty. Her first novel, The Old Drift, was published by Hogarth/Penguin Random House in 2019.