My Year of Mourning: Mapping the Full Cycle of the Loss of My Father

Merissa Nathan Gerson’s Notes on Grief

When my father died unexpectedly on December 1, 2019, of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, I tried to read grief books. First, I read C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed, where he simply outlines his experiences after the death of his beloved wife.

“An odd byproduct of my loss is that I’m aware of being an embarrassment to everyone I meet,” C.S. Lewis writes. “To some I am worse than an embarrassment. I am death’s head.”

In A Very Easy Death, Simone de Beauvoir did the same thing. She described her experience with the loss of her mother: death calling, a mother declining, dignity and the lack thereof. Death memoirs broke a taboo: they admitted the gritty raw suckage of death and dying.

I read angry books on grief, poetic books on grief, profound books on grief: but what I needed, for my grief, in all its particularities, did not yet exist.

Despite the solidarity in the raw truth of memoir, I wanted something that explained more of the basics: why was I sick to my stomach all the time? Why couldn’t I ever sleep? Why did my flashbacks make me cry so hard? When on earth was this going to end? And if this was the basic thing of life: that when people die we splinter and split apart, why was it being painted a sickness? Why did I have to wait to learn this terrain in trial by fire, why hadn’t anyone prepared me for this shit?

*

I began to take notes:

Note – May 28, 2020:

Is it safe to grieve around others?

Note – April 5, 2020:

Personal protection in times of extreme vulnerability.

I was building a catalog of my grieving process, a map of these symptoms, these existential questions, this horror, as I worked to understand how to live a life without a once vibrant father. I wanted a map for me, and for everyone trying to get close to me.

Note – July 3, 2020:

Navigating other people’s memories.

I wanted help moving through it. Not mandates, not quick plans for making the grief go away, but tools for how to navigate, marinating in it my way, on my clock, with all the strange tools I had acquired over the years.

Note – July 19, 2020:

Making your own space for remembrance.

I wanted something I could give to the people around me who were navigating loss, but it felt, almost more importantly, for the many who were terrified of it from afar. I wanted to equip my support team to support me.

I tracked the ingredients of my year of mourning. One by one.

Note – August 7, 2020:

Bowels and body and the hellscape of grief.

Note – August 20, 2020:

Grief compounded.

I did Google searches all the time and they came up short. I wanted everything simplified, and lighter, and funnier. I was almost desperate to train those who hadn’t yet known death’s head how to be with and understand those of us that had.

Note – September 7, 2020:

Chosen family. When to be alone and when to come together.

It wasn’t even a year since my father had died, I hadn’t completed my Jewish mourning cycles and rituals, I was still a raw and cracked egg, and this book was born amidst my half-cooked grief.

“Here,” I imagined offering my map to someone without a dead parent trying to date me, “this should take the edge off.”

Or, “Here, maybe if you read this you won’t be so afraid of me? Of my Dead Dad? Maybe you will stop telling me how beautiful it is that he’s shining down on me, and now we can sit together in the sadness of what is: my Dad is buried and gone. No more blood flow.”

I continued to take notes obsessively.

Note – September 19, 2020:

Breaking glass, punching walls.

I did this wiggle through my days of grieving, letting it move through me, and at once watching my grief, as if I were now my own specimen. It was somehow possible to drop into feelings, and also to emerge with a cognitive sense of witnessing those feelings. It became a walking and living and breathing meditation: Breathe. Grieve. Watch. Catalog. Organize.

Note – September 21, 2020:

Crying when you least expect it.

I became this observer of the power of all things solitary, of how single people build community, and how all of these things could help one to grieve, to tend to loss, to begin to make themselves a bit less invisible.

I was building a catalog of my grieving process, a map of these symptoms, these existential questions, this horror.

September 23, 2020:

What happens with no community?

Choosing one, finding one. Power of togetherness, even over Zoom.

I ordered Heidi Murkoff’s What to Expect When You’re Expecting because it struck me the guide to birth was similar to the guide to death. Wasn’t she ultimately guiding her readers through the profundity of the unknown, the rupturing of the body, a nine-month cycle that changes everything forever?

Note – October 7, 2020:

I don’t need the stages of grief; I need to understand my body and my feelings and my life.

I loved how she divided her book, how certain pages stood out with needed information in clear and clean ways. Once my notes became a real manuscript, I copied this style for the guidebook elements. I wanted my book to be almost like a magazine, fun, but heavy, real, but light, all of it at once, a book that could be digested, and also was as biblical as What to Expect When You’re Expecting.

Note – October 11, 2020:

“Accept” is an annoying word.

I learned, in the process of transcribing my misery, and my triumph, to be the party in the evening, the woman in my arms all night gripping me as I imagined the apocalypse. I became a world alone. Sure, I had friends on the phone, and writers supporting me by text and Facebook chat. I had family members who scooped me up on Facetime calls when the world inside of me was almost too crushing to endure.

Note – October 18, 2020:

Solitude as divine

But a mirror, a mirror of my woes, of my triumphs, of my fears? I became she, and she I. I was a we, a thou, an us. I and I.

Note – October 26, 2020:

About witnessing and convening with self.

Once the map became a book, I remember finishing one version of the draft, living and reliving and then reliving again the death scene—it was so important to me to write the death scene, a la de Beauvoir, to shy from nothing short of the morgue. It had not served me to conceal death. I wanted others to have what other writers gave me. A map to the horror.

Note – October 29, 2020:

Grieving who you thought you would be.

Write a book called: The Power of Negativity.

And the minute I finished the draft the lights went out, an explosion happened, a transistor exploded. I was in New Orleans in the pitch-black dark. It happened to be the coldest day in recent Louisiana history, below freezing, forcing me away from the work, away from my house.

Note – October 31, 2020:

Ancestors.

No practice works if you don’t do it.

But first I sort of shoveled myself onto the bed. My limbs hurt. Everything hurt. It was like death, from writing about it, had seeped into me. I was momentarily destabilized, stunned, legs practically rubber. It was as if, for a moment, I was gone. I called my mother then, and something animal came out of me, a wail I didn’t even recognize. I had been scrubbing my words up against the grave, so close, I had become the darkness.

October 11th, note to self:

It is really you that supports you in your grief.

By November, I stopped reading about grief. I stopped asking. Something happened when it seemed I echoed death, and then was able to bring the blood back into my limbs. I realized that I could, after death, return to life, to breathing, to moving a body. I was not afraid. My grief was enough. I had catalogued a full cycle of horrifying loss. I had become the map.

__________________________________

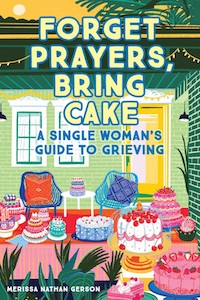

Forget Prayers, Bring Cake: A Single Woman’s Guide to Grieving is available from Mandala Publishing. Copyright © 2021 by Merissa Nathan Gerson.