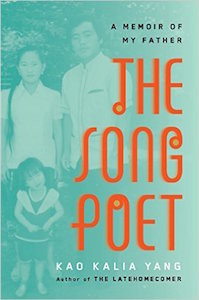

My Father the Song Poet

Kao Kalia Yang Comes To Understand Her Machinist Father as a Literary Force

My father would never describe himself as a poet. In Laos, he was a fatherless boy. In Thailand, he was a refugee waiting in the dust. In America, he is a machinist. Through it all, he has been a poor person yearning for a father and living to be one.

My father is Chue Moua’s husband and the father of seven children, five girls and two boys. My father says that on his gravestone he wants it known that his wife and his children are his life’s work. He would love it if we could add: “All of Bee Yang’s children became good people.”

I am the only person I know who describes my father’s work as poetry. I am not referring to the pieces of hard metal he polishes, the rough edges he makes smooth, the coarseness he evens into shine. I am talking about the songs he composes, day and night, in Hmong, our language, his kwv txhiaj.

My father is not a writer. He does not write down his compositions. He is a singer. He sings them.

It has taken me a long time to gain the courage to call my father’s work poetry. For much of my life I have described my father to the world as a machinist, not as the poet I know him to be. I didn’t have a way of conveying how being my father’s daughter has taught me not how machines work but how the human heart operates.

I grew up hearing my father digging into words for images that will stretch the limits of life for my siblings and me. In my father’s mouth, bitter, rigid words become sweet and elastic like taffy candy. His poetry shields us from the poverty of our lives.

On the colorful, woven plastic mat in the middle of our living room floor, we sit around my father. We look at the walls with him. The mold growing wild becomes the backdrop of the beautiful paintings we see on television, the peak of this mountain, the descent of that river, the sliver of tree that clings to life on the edges of the rocks, open and exposed. We point at the things we did not see before our father’s words gave them shape, alternatives, possibilities. My brother Xue sees a crane at the river’s edge. Sib Hlub points to the sky with its cloud families, gray and rumbling, and whispers of bad weather approaching. For a moment, we are living in a priceless, ageless piece of art.

In the deep of winter, after months of unceasing cold, my father points outside our front window at the ice-covered mounds of snow shining in the bright sun, in a cloudless sky of blue, and says, “Look at the garden of winter, the snow flowers are blooming today.” My siblings and I leave our places by the big heater with its opening’s single blue flame, and we look out into a picture of winter we thought we had grown sick of. We blink against the shine. Beneath our lashes, in the sliver of open eyes, stars twinkle in the colors of the winter rainbow. The children marvel while my older sister Dawb and I take deep breaths and breathe foggy air onto the glass pane. We draw the flowers of early spring on the cold, wet glass with our fingers: buds of tulips and daffodils, the bursts of dandelions and fragrant lilac blooms. The sweet, clean scent of magnolia blossoms and the images of the flowering trees—stocked with soft white, pink, pinkish-red, purplish-white petals—remind us that warm weather and abundant flowers are coming our way. The world of winter becomes bearable in the promise of spring.

In perfect pentatonic pitch my father sings his songs, grows them into long, stretching stanzas of four or five, structures them in couplets, repeats patterns of words, and changes the last word of each verse so that it rhymes with the end of the next. He is a master at parallelism, the language is protracted, and the notes are drawn deep and long. The only way I know how to describe it as a form in English is to say: my father raps, jazzes, and sings the blues when he dwells in the landscape of traditional Hmong song poetry. Different shapes come forth from the dirty places, different possibilities are born in the shadows of our lives, and windows emerge in the places my brothers and sisters and I have only ever seen walls.

I grew up surrounded by my father’s words. They are familiar to me as the wind outside the thin walls of our old house across the different seasons.

In the cool of autumn, the wind carries the dry crackling leaves along the sides of York Avenue. Empty cans roll along the broken cement walk and abandoned plastic bags fly with their ghostly goods. An occasional voice is carried in the wind, a brother looking for a sister as night falls, a baby crying for its mother, the bark of a hungry dog.

In the cold of winter, the wind blows the snow off the ground and waves of white come sweeping across our tiny stretch of lawn and hit the house in sprinklings of icy snow. Invisible streams of air seep through the cracks of the old windows and the smell of our rice-scented home swims in the currents of cold. Outside, the sound of police sirens resonates in the rippling, urgent winter winds.

In the warmth of spring, the wind transforms the empty parking lot by the corner Laundromat into a field of fallen petals as crab apple trees release their blooms and the hard pavement feels the soft brush of tender, ephemeral beauty. Wet rain falls into shattered concrete and the pools of black water lie still for the pink and white and red petals to swim. The wind carries the voices of laughing children into our house, as we watch the petals sway to and fro in the dark puddles across our street.

In the heat of hot summer, the green grass grows while the yellow dandelions die, and in the wake of their demise, the wind carries their spirits and their seeds across open lots, rotting houses, small yards, littered avenues, and everywhere there are little parachutes of pollen floating away. Late into the night, we listen to the voices of friends and neighbors talking outside on their porches, hear the clinking of cans, turn our heads toward their laughter and their tears, and the wind loses its appeal for a season because the pull of people grows strong across the fertile green.

My father was a young man who carried on his broad shoulders sacks of hundred-pound rice bags while I ran fast as I could to open the front door lest he beat me there. Then came the season when there was no danger that my father would get there before me, when I stood with the door wide open, my fingers soft against the hard wood; I watched my father age with each sack of rice we bought and ate. My wait at the front of our house grew long as my father’s steps grew heavier on the ground and his shoulders shook beneath the burden of feeding us.

Once in a while, there was something undeniably lonely that seeped into me when I caught and understood pieces of my father’s songs, heard the tears leaking through, creating ripples of husk in the smoothness of his voice. As a child peeking through crowds, my hand secured in my mother’s, I watched groups of people cry around my father’s songs, and I saw how sorrow could be shared.

My first absolute memory of my father as a poet happened at the Hmong American New Year in November of 1989. Someone had put my father’s name down as a performer at the annual celebration. We were in the old Civic Center, now renovated and renamed. The younger kids hadn’t been born yet. They were still high up in the clouds, in their race across the sky. It was only the five of us: my mother, my father, Dawb, me, and Xue, our baby brother. My mother pushed Xue in the old stroller we’d gotten from a garage sale during the summer. Dawb was ten years old. I was in the last months of my eighth year. It was the first year I was growing out my hair from its Thai schoolgirl bob, and I had borrowed my mother’s hair spray and done a tiny pouf on the bangs that were getting long over my eyes. My father had not been excited about my decision to let my hair grow out—he thought I was too young, but my mother had agreed that it was time I learned how to take care of long hair, so my father had relented. I was learning how to be critical of my father that year, our second year in America.

My father owned two suits, the brown one that Grandma had paid for in Thailand and then a black one that my mother had chosen for him at Men’s Warehouse. He wore the black suit to the Hmong New Year that year. His straight shoulders lifted high in the suit. My father looked like a man who worked in an office building. My mother wore a black sweater with shiny beads, purple pants with seams down the front that she created carefully with the iron, knee-high stockings that made the skin of her feet dark and smooth, and a pair of heels that clicked gently on the floor with each step. When my mother and father walked together, I thought they both looked good enough to be secretaries; the only challenges to the image were the sleeping baby boy in the stroller, Dawb and me, and the backdrop of Hmong people in their finery.

The New Year celebration was a day dedicated to dreams, dreams of prosperity for the Hmong people and the Hmong family. Since our arrival in America in 1987, my family had gone regularly to the celebrations. We all looked forward to the two days of seeing and greeting family, friends, and strangers. Our mother and father would stop to chat with the adults they knew while Dawb stood solemnly by and I bit my bottom lip and tried not to look too shy. Occasionally, I sneaked behind the stroller to feel the stiff tiny pouf of hair on my forehead with my fingers. In the bright fluorescent light of the Civic Center, the yellow in everybody’s skin changed into a pale blend of whitish gray. The women with lots of makeup looked like clowns. The thin old men with their hollowed eyes brought to mind the plastic skeletons at the stores during Halloween. Despite these scary possibilities, there was movement and color all around, and more comfort to be found than fear in the big building. I imagined that we were all performers in a great circus.

That year had begun like the previous years: My family and I spent the first hour or two walking around the large arena admiring the glitter and noise that surrounded us, the clinking coins and swishing silver bracelets, women in heels that clicked on the hard floor along with the gentler clicking of camera shutters. We stopped to look at the young men and women who stood in lines and threw handmade cloth balls sewn with silver and gold thread, or the familiar fluorescent green of tennis balls, at each other. It was an old courtship tradition. We made room for the old men and women who helped each other through the crowds, stopping every few feet to admire the beauty of the young. All around us there were little babies like Xue in their strollers with the sunshade drawn forward despite the fact that there was no sunshine to protect them from. Some of the babies looked intently at the world around them while others fell in exhausted slumber, heads sagging to rest against the sides of their strollers. A few of the sleeping babies were drooling. I checked Xue regularly to make sure that his mouth was clean. Our family moved slowly through the standing, shifting bodies.

When we heard “Bee Yang, Bee Yang, if you hear this please come to the stage. Your name is being called for a traditional kwv txhiaj performance. Bee Yang, Bee Yang, please report to the stage,” it did not register that they were calling the Bee Yang we knew. It was not until the familiar faces of family, aunts and uncles, second and third cousins, emerged from the crowd and each of them pointed my father toward the stage that we knew our father was being called.

My father shook his head. He was like me. He was shy. He did not want to go on the stage. He shook his head slowly again, this time smiling. The faces did not disappear into the crowd. They came closer. When old friends and acquaintances started pulling him toward the stage, my father looked at my mother and shrugged his shoulders, both his hands raised, palms up. He allowed himself to be led toward the sound of the amplified voice calling his name. Near the empty outskirts of the stage, where the people had cleared room so that the raised platform seemed a small island in the sea of smooth concrete, my father straightened his spine and walked slowly to the woman and the man waiting for him with a microphone extended. My father’s name was announced as a contributor to the New Year’s festivities. The people around me applauded. I stood by my mother, my older sister, and my baby brother in the crowd, and we watched my father take the extended microphone from the male host, shake his hand, nod to the female host, and then climb the stairs to the stage. I was nervous for my father. I was also scared that I would be embarrassed by him. I had heard stories of how he had been requested to sing at the Hmong New Year’s celebrations in Ban Vinai Refugee Camp, but it was not something I could remember. I imagined the dust rising in the yellow dirt field, the young men and women standing opposite each other, my father standing on a makeshift stage, his voice muffled by the debris of our lives in Thailand, struggling for his voice to be heard. I knew that my father’s singing was valued by the adults. I looked at the faces of the men and women standing still, eyes on my father, and I realized that they did not know that I was his daughter. I was just another kid in the crowd of Hmong people celebrating the New Year. The fluorescent bulbs continued to cast their unfriendly light upon us. If I grew embarrassed, I figured I could always pretend I didn’t exist.

When my father began to sing, I watched him as a stranger would. I saw a man standing still, his left hand holding a microphone, his right smoothing the side of his suit jacket. There was firmness to the set of his jaw, an appearance of reckoning in his straight stance. The steadiness of my father’s voice reached out to me. His “Niajyah . . . ” the preamble to the form, called out across the crowd. He looked at the people, from one side of the arena to the other. He trained his gaze high over us, at the people sitting up in the stands. As he sang, it seemed he saw through the steel beams and cement walls that surrounded us and out into the world we had ventured from. It was a song of grieving. The song was a cry for a New Year that once was a time for rest after the bountiful harvest, for the old to call upon the young, for all to walk together toward the future of a sun on the rise. There was a moment of transition, and then my father sang, “The flash of light that turned the world dark, the sounds of exploding suns across the sky, the cries that rang forth in the place of laughter.” A new quiet entered into the arena; his voice softened, his tones lengthened. “Lost are the ones who run through jungles without shoes, the young screaming for their elders to run faster, a giant moon on the other side of a river, the glittering water a mirror for what will come.” People started weeping. Men and women reached into pockets and purses and came forth with folded pieces of wrinkled napkins; they tore up the napkins to share; those with nothing in hand began wiping away their tears on their sleeves.

I saw my father bend his head, searching within for the words that would send away the sorrow he had unleashed. He walked a few steps forward, to the edge of the stage, and raised his right hand to the audience, opened his palm, closed it again, slowly dropped his hand, and allowed the fingers to round into a fist. My father sang, “A brother and a sister search the world for each other, one caught on the side of the trees, the other has traveled far across the wide seas.” His rhythm and his rhyme were one. His words grew louder, his voice stronger. He sang: “Like the eggs hatched upon the same nest, they huddle to themselves and call out for the same feathery bed. The future takes us to the same place, our hearts hover close to the same space . . . where once our mothers and our father held us close, and made us safe.”

My fear of embarrassment vanished. In its place there was no pride, just an understanding of the man I had always seen exclusively as mine, now standing before his people, with his heart open, bleeding hardship and harrowing hope. The words had nothing and everything to do with my being in the big arena. There was no room for refusal, for thoughts or ideas, it was all just a moment felt, emotions bubbling forth from losses the Hmong had endured. In his song, I was no longer young. I was one with a people who had lived for a long time, traveled across many lands, a people clinging to each other for a reminder, a promise, of home, that place deep inside and far beyond where the Hmong people had hidden our hearts so that we could heal. There was nothing to be embarrassed about.

After my father’s song ended, there was a stretch of silence, noses being blown, breath exhaled, and then the echoing ring of applause. Men and women rushed toward him at the stage’s edge and they clapped their hands on his back as he walked back down to the floor. Some wept on his shoulders. My mother stood aside, just a woman with her children, and we waited patiently for him to make his way toward us. I slipped my hand from my mother’s and moved away from my family so that I could see the moment when they met, my mother and father. I watched how my father approached my mother, my big sister, and my baby brother sleeping in his stroller. My father placed both his hands on Dawb’s smooth hair. He leaned close to my mother and whispered something in her ear. She turned to him and smiled and nodded, and then I watched the smile fade from her face as she started looking for me.

In the car home, we were silent. There were words that I wanted to say but did not know how or why they felt necessary. I didn’t tell my father that I’d finally listened and found meaning in his songs. No longer were the phrases just bits and pieces of a long story floating from the past into my present. I did not say that I was not embarrassed or that I thought he had done a good job. All I did was stare out the car window and hear the work of the wind in the dark, cold night. I squinted hard at the lights in the distance. I urged my world to dissolve into a blur of light circles. Dawb sat quietly beside me, lost in her own thoughts. Her new shoes were a small heap on the floor of the car beneath her dangling feet. Xue, our baby brother, slept in his car seat between us. Our brown Subaru made its hiccupping noise at every stoplight, and I watched puffs of smoke balloon behind us when the lights turned from red to green. I could smell the exhaust from our car. I hoped other people weren’t able to smell it as I did. I listened to the wind blow hard against the car. I felt the car shake. I did not want to tell my father that his song had shaken my heart, taken me to a place that I did not want to visit for fear I would never return. Now that I had heard, I could not forget the suffering and sorrow of the Hmong story.

After my father’s Hmong American New Year’s performance we received many calls from friends and family, from strangers who had heard him, and from people from other states who had heard of him, asking my father to please make a tape of his songs and send it to them. The people said that they would be happy to pay my father for a recording of his songs. The winter passed and the phone calls did not stop. My cousin Pakou was married to a man in a band who played and recorded music from his basement. The cousin-in-law had the equipment we needed to make a cassette album, including the ability to duplicate taped recordings. After a particularly busy day of the phone ringing with strangers’ requests, my mother approached my father and said, “You love your poetry. Let the people love it with you.”

My cousin Pakou and her husband lived in a town house in the Roosevelt Housing Project. My father and I drove into the busy parking lot on a gray day. It was early spring. The afternoon air was cool against the bare skin of my arms. The uniform yards, small designated squares of grass, were beginning to green. My hair blew against my neck and I felt the maturity of my years scratching at my shoulders; it was the first time I was going to have long hair. My father offered his hand out to me and I considered it for a brief second before I extended my hand into his. We held hands as we walked to my cousin and her husband’s tan wooden door with the small peephole that was distinguishable from the other doors only by its number.

My cousin opened the door with her usual huge smile, and the familiar aroma of sweet coconut milk wafted into the cool day. We greeted her children and then she ushered us down the staircase into their basement. At the bottom of the stairs, in the darkened room, I saw her husband behind a dashboard of controls, red and green bars rising and falling before him on black screens. The corners of the large cement-block room were full of cardboard boxes stacked in pyramid-shaped heaps. In the center of the basement, there was a microphone and a chair on wheels with a handle underneath to adjust the height. There were sound boxes and amplifiers connected with black wires that tangled on the floor. I got to sit with my cousin’s husband on a stool behind the dashboard during the session. My cousin came down the stairs quietly with a cup of cool, slippery tapioca dessert for me.

I sat quietly spooning the long strands of tapioca into my mouth, careful not to slurp the sweet creaminess going down my throat. With my tongue, I pushed the round tapioca pearls against my front teeth, trying to squeeze them through the small spaces. It baffled me how my father could just recite his songs from memory. They were long, winding tales of rhymed poetry. Each was about ten minutes long. I thought that eventually my father would have to close his eyes, search for the words in his head. For someone who had so little schooling, for someone who forgot clinic and dentist appointments and our birth dates, my father had an astounding memory for his songs. He kept his eyes open the whole time; he looked at my cousin’s husband and me alertly, lost to no one. Between sips of water and the occasional clearing of his throat, my father made an album of song poetry in a single day. Once my amazement over his memory dimmed, I lost track of his words and focused on savoring the sweetness in my mouth. The tapioca cup was long empty before I heard the final beep and my cousin-in-law say to my father, “The final track has been recorded.” The door closed gently behind us with Pakou and her husband’s words of “Farewell” and “Come again.”

The day was done. The sky was a blanket of black. The stars glimmered down in their scattered fashion. The cool breeze had turned cold and little bumps rose on my arms. I moved close to my father. He placed his arm around my shoulders. In the dark, the night felt more autumn than spring. On our way to the brown Subaru in the crowded lot, I couldn’t stop my shivers. It was easier to see the stars in the sky than to see into my father’s face in the night.

My father coughed all the way home in the car. He told me that his voice was no longer what it had once been. He laughed and said that he had gained too much weight; there was a heaviness in his throat now when he sang that had not been there before. I wondered if you could put your throat on a special diet. I had seen old men and women whose throats were weighed down by folds of skin, even if they weren’t fat. I had heard the age in their talk. I assured my father that he didn’t sound like them yet, but the thought of him one day sounding like the old Hmong men at family gatherings made me sad. I just shrugged my shoulders. Maybe he saw. Maybe he didn’t. My father didn’t talk much after his comment. His voice had grown tired in the studio. The headlights of our car took us to our own busy parking lot in the McDonough Housing Project.

Bis Yaj: Kwv Txhiaj Hmoob was released in 1992. Like my father, the title of his album was very concrete, Bee Yang: Hmong Song Poetry. It was a Hmong song poetry hit in the early 1990s. The album consisted of six songs. They were songs of love, of yearning, of losing home and country. We sold the album at the 1993 July 4th soccer tournament in St. Paul. Dawb and I tried to make the family’s booth more modern and American by attempting to sell boiled hot dogs. We thought the American fare would bring in young people. It didn’t. In fact, we lost money because our shriveled, pale hot dogs were unappetizing next to the coolers of steaming sticky rice and the smell of barbecued ribs, flattened game hens, Hmong sausages, and the sizzling pork skin that crackled and popped on the hot grills. The scent of good food came wafting in from neighbors on either side of us while we stood looking at our boiled hot dogs, some with slimy relish on them, others with just ketchup, and a few with bright yellow mustard. Young people passed before our booth with plates full of papaya salad, leaving the taste of hot chili peppers, the sour of lime, and the sweetness of tamarind in our mouths. Only a few kind men and women looked in on our hot dogs after they had stopped by and purchased our father’s cassette. The sale of my father’s tapes made a profit and allowed us the loss of our hot dogs.

After the tournament, we received more phone calls from people asking that we put the cassettes in local Hmong grocery stores so that they would be more accessible to the community. My mother, my father, Dawb, Xue, Sib Hlub, our new baby girl, and I traveled throughout Minneapolis and St. Paul in our Subaru, dropping off tapes at stores. For the next few years, my mother and I would collect whatever money there was (once the grocery stores had deducted their percentage) and restock supply as necessary. My father, Dawb, and the babies never came into the stores with us: they said they were shy. My mother said that selling your art is nothing to be ashamed of, although once we were in the stores it was always hard for her to ask about the money. We would stand for long minutes between aisles of dusty cans of Chinese bamboo shoots, coconut milk from Thailand, and rice flour from Vietnam. The scent of star anise powder surrounded us, a little like cinnamon but reminding me of the tree barks my grandma kept in her medicine bag. I examined the packaging of the food on the shelves as I held my mother’s hand to give her silent support.

My father’s album was a small venture, and in the end my parents made a profit of a little more than five thousand dollars.

Originally, my mother wanted to invest the money they had made in a second album and my father agreed, but we were going to school and needed new clothes and books and pencils, and each year Dawb and I wanted new backpacks. Then Xue and Sib Hlub started school, too, and then Shell and Taylor were born, and eventually all the money was gone, translated into food on the table and supplies in our bags. My mother and father never had the funds for a second album, although my father spent years composing songs. He would record one or two on our old tape recorder, label the cassette, and put it away. We saw him doing this but we did not ask any questions about his poetry. We did not ask him what the new songs were about, or offer to listen to them. We understood his kwv txhiaj in American terms, as little more than our father’s hobby. There were mornings, afternoons, and evenings when our father would recite his songs to his brothers on the phone or to my mother when they found a moment together. All around us, we heard fragments of his words coming together in song and we took it for granted that this would always be so.

My brothers, sisters, and I never thanked our father for the money his first album made or regretted that a second one was not possible because we had used the money, and he never expected us to.

When Youa Lee, our father’s mother, died in 2003, he forgot all his songs. He had never written them down. They were either recorded on old scratched tapes or memorized in his heart. His heart had broken. The songs had leaked out. The poetry was gone from our house.

I was thirty years old when I took out my father’s cassette album and listened to it. By then, I had become a writer. By then, I had learned enough about poetry and literature, about art, to see my father as a literary force in my life. By then, I had grown to understand that my father was a fine poet in the Hmong tradition, and as poets across traditions and time have done, my father has suffered for his poetry. What I found in the old cassette tape, however, was not a work of suffering. The first time I listened through my father’s album as an adult, it was striking to me that there was humor, irony, and astute cultural and political criticism. There was so much more than the hurt that I thought he had harnessed in his songs. There was the beauty of endless hope. Hearing his voice on the side of a tape scratched by time, then turned into a CD without tracks, a continuous stream of stories, I felt I could hear my father speaking to me, not as his daughter, but this time as a fellow artist.

My father is a poet. My father’s art is his kvw txhiaj, his song poetry. His poetry complicates what he says to us, my brothers and sisters and me. We are not the walking and talking, quickacting and hard-feeling products of his creativity; it is instead the songs that he composes, songs born deep inside, rising forth to find improvised life in the very breath that he breathes, that are his art and his contribution to our world. Because the second album never came out, because he turned his words into grains of rice and strings of meat to feed us, shirts and pants and underwear to clothe us, my father has allowed us and the people in our lives, for a long time, to believe that we are the output of his life’s work. Because my grandmother died and she took with her the shelter of her love, our father’s heart could not save the beauty he had stored inside from disappearing. I want my father to understand that aside and apart from my mother and his children, he has offered the world a gift all his own.

I want to tell Bee Yang that once upon a time, at a Hmong American New Year’s celebration, his words sank deep into the heart of a little girl. I want to tell him that the seeds his words planted sprouted into life and that way down where the water of her tears well up, they have grown green, stretching their limbs far to touch the world with their blooms. I want to show him that my siblings and I have grown rich and full from his songs, journeyed not only to the Hmong past but to our possibilities, and while I will never know kwv txhiaj the way he does, I want to pay my respect to his form and the many Hmong men and women who share it.

When my first book, The Latehomecomer: A Hmong Family Memoir, came out, my family was interviewed by a local public television station. I sat between my mother and father on our brown microfiber sofa in our living room in Andover, Minnesota, with its faded 1970s wallpaper. The camera was on us. We each had a microphone tucked into our shirt. The hot summer breeze entered through the old screened windows and ruffled our hair.

The young producer, breathing heavily with her belly round with child, asked my father, “How does it feel to be a writer? How does it feel to give birth to one?”

I couldn’t look at my father as I interpreted her questions. I couldn’t look at my father as I interpreted his words. I looked at my small, crooked fingers, clasped together in my lap. I watched the skin of my hands, plump with the moisture of summer and youth, grow tight around the bones of my fingers.

My father’s words in response to her question: “I am not a writer. I can barely write my own name. My daughter has made possible in English the stories I cannot tell.”

Excerpted from THE SONG POET: A Memoir of My Father by Kao Kalia Yang. Used with permission of the publisher, Metropolitan Books. Copyright 2016 by Kao Kalia Yang.

Kao Kalia Yang

Kao Kalia Yang is an award-winning Hmong American teacher, speaker, and writer. Her work crosses genres and audiences and centers Hmong children and families who live in our world, who dream, hurt, and hope in it. Yang’s writing and speaking are concerned with the plight of refugees from around our world, ideas of belonging, and the depths of the human experience. She holds an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from Carleton College, was the 2024 Star Tribune Artist of the Year, and is a Guggenheim Fellow. Kao Kalia Yang lives in St. Paul, Minnesota with her family. Learn more at kaokaliayang.com.