On Sundays, I always wanted to go to the park in town with Mum. She preferred going to the river, not to the sunbathing parts but to places that only a few people knew about, peaceful places. I didn’t want peace, though. I wanted to kick a ball around with my friends. A peaceful place, for my mother, meant somewhere she could read. She never used to play with me, she barely even talked to me, just as she barely talked to anyone, except when necessary, except, just sometimes, to her children. I was the youngest of the three, the little boy who still needed to play.

Mum didn’t like the park because of the people. Not simply because they were there, not simply because she always wanted to be alone, but because the people in this park were worse than other people. They were dirty and raucous, aimless and hard to shake off. All the poor people, so poor they didn’t even have a driving licence, let alone a car, drifted to this park on Sundays, gravitating towards a very big old lime tree surrounded by graffiti-scrawled benches. There were lots of spelling mistakes on the wooden benches, but not on the seemingly indestructible bark of the tree, and, rushing around the benches, jumping over them and squirming underneath them, there were always plenty of children. I liked that, and Mum wanted me to be happy, so we went there, abandoning the calm of the water and the riverbank, leaving behind the regular, comforting sounds of the current, the rustle of pages and the echoes of my solitary football. Mum always said yes in the end. She would sit down beneath the tree, holding orphaned in her hands a book she knew she wouldn’t be able to read, but with the pleasure of seeing me smiling and playing with the other children.

Mum came from the countryside and always talked about how she longed for the moment when she could go back there.

On that particular Sunday there were lots of children with their dubious looking parents, but also quite a few younger people without children, sprawled comatose on the benches, finishing off their night out in the middle of the afternoon in the lime tree’s shade, guarding their dogs and their beers with their feet. I could see the fearful, fed-up look on Mum’s face as she sat down as far from them as possible. One of them, awake, bored and already tired of life, started trying to chat her up. She replied politely that she wanted to read, and she did actually start to read, once she had encouraged me to get the balls out of the bag (a basketball and a football) and to go and introduce myself to the other children, who were also laden with balls and on the lookout, like me, like everyone, for new friends. But I wanted to talk to Jérémie. He had just introduced himself, holding out his suntanned hand, so I knew he was called Jérémie. He looked about the same age as my older brother, and Mum pointed this out. I’ve got a son your age, you know. He looked nice and he looked canny. He’d already worked out that if he wanted to seduce my mum, he had to win me over. He started to explain dribbles and passes to me, all sorts of things about football and basketball, and even lots of things that had nothing to do with football or basketball, things sport could teach us about life: altruism, respect, team spirit, playing straight, sticking to the rules, getting along with others. And at the same time he told me about his own life, a life that was already slipping by, the abandoned sports studies diploma, the job he claimed to have as a sports coach, his problems. I could tell he was talking to Mum, really, but in just a few minutes he’d become my best friend in the whole park.

Mum was trying to focus on her book, checking on me once in a while as subtly as possible so that Jérémie couldn’t catch her eye. Whenever he did manage to, he’d begin reeling off heavy-handed compliments about the blue of her eyes, that blue she had passed on to me, undiluted, a blue bluer than the river on a sunny day, the blue of a cloudless winter sky, astonishingly bright in her ageing face, worn by time and sadness. I was a bit jealous but only a bit, because I knew I was her favorite. I knew he didn’t have a chance, and I made the most of his loneliness to play with him, because she never wanted to play with me.

She had used up all her patience with my brother and sister and I don’t think she could stand any more ball games. She could only stand books and walks. She loved being with me and going for walks with me. She loved me. She just didn’t love the town, or the people in town, or the dirt in the streets and the park. Mum came from the countryside and always talked about how she longed for the moment when she could go back there, which irritated my older sister and me because we loved being here, near the shops and the rough part of town, the basketball hoops and the goalposts. Our brother lived in an even bigger town which seemed a dreamland to us, or a fantasy land, as Mum said.

Mum used to say that silence doesn’t exist, that there are always tiny sounds in the background, muted and barely perceptible.

When she was young, she didn’t play the same sorts of games as we did. She daydreamed among the trees, did jigsaw puzzles without getting bored, spent lots of time drawing and already read a lot. She lived alone with her dad in such an isolated place that it took hours to go and visit her mum. It was so far from the city crowds that you could tell when one of your neighbors was passing just by listening for the sound of them walking in the snow, counting the number of steps by the dry, tearing sounds, shocking in the silence. Mum used to say that silence doesn’t exist, that there are always tiny sounds in the background, muted and barely perceptible. And she was an expert in barely perceptible things. Her whole childhood was made up of them. Mum had red, prematurely aged hands, as if she’d been a cleaner, a laborer or a farmer, but she hadn’t done any of those things. She just took so little care of herself, her hands, her face, anything to do with her appearance, so little care that it was almost a bit strange, as though she wanted people to think she was someone else. I gazed at her hands holding the book and missed a pass from Jérémie. His little dog started barking and jumping around like a mad thing.

My distraction was driving the puppy mad with excitement, as though each kick I missed pressed a button on a remote control linked to his tiny body, and he kept rushing after the lost ball, a noisy bundle of energy. I followed this joyful little dynamo, forgetting Mum for a minute or two, but when Jérémie started telling me how his dog had picked up the scent of a fox the day before, as it was nosing through the bins, I turned to her straight away with a knowing smile. When she was a little girl, Mum had killed a fox with her bare hands to put an end to its suffering. She had often told us about this memory and, more often still, we’d asked her to tell the story again and again. It seemed a miracle to me that a fox could stray into town, like a reconciliation with Mum. She looked at me and returned my smile, but with a finger to her lips to say that we should keep that story in the family. I felt the same. She took a snack out of her bag for me. She never forgot the snacks or the water or the books. Or even the balls.

I ran over to sit next to her, and Jérémie made one last attempt to get Mum’s number, gave us a carton of apple juice, then finally said goodbye. He woke his friends and whistled to the dogs. They all left without closing the gate and as they went out another dog came in, an old white dog with wobbly hind legs. He didn’t have any of the bounce or playful barks of a young dog, but that didn’t stop him chasing after the ball with me once I’d finished my sandwich and Mum had picked up her book again.

__________________________________

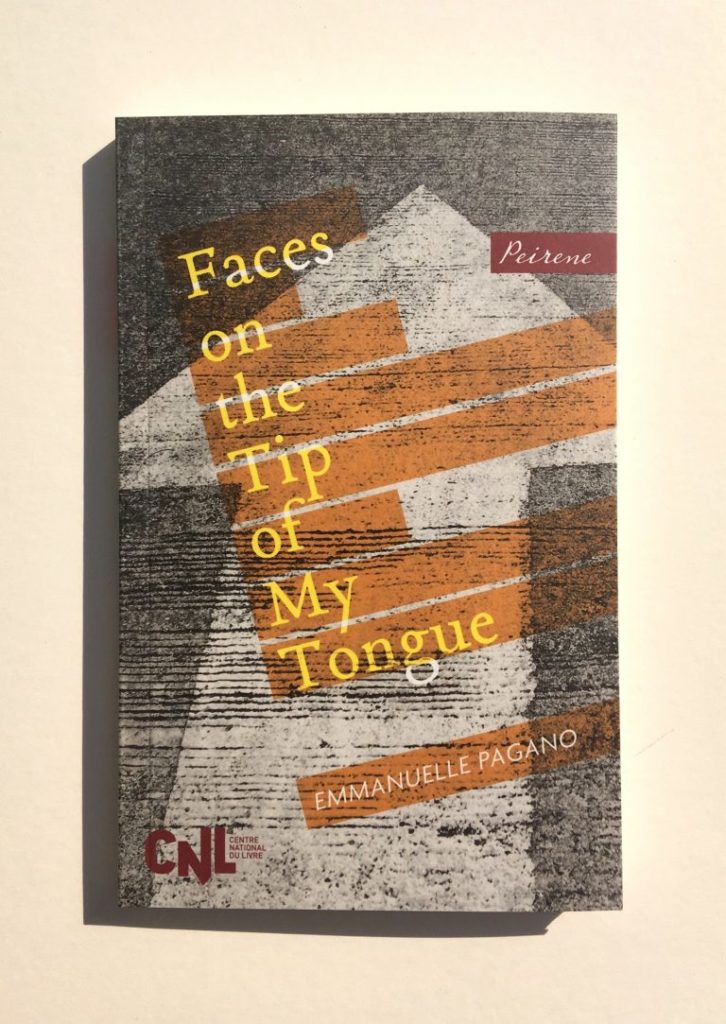

From Faces on the Tip of My Tongue by Emmanuelle Pagano, translated by Sophie Lewis and Jennifer Higgins. Used with the permission of the publisher, Peirene Press. All rights reserved.