Multiple Narrators, Multiple Truths: A Reading List

Sophie Ward Recommends Jennifer Egan, Han Kang, the Brothers Grimm, and More

In my teens, I read only Victorian novels. The multiple narrator is such a prominent feature of 19th-century fiction that it’s possible I internalized the device inadvertently. Books such as Middlemarch, Frankenstein, and Wuthering Heights fed my already over-exercised imagination to the point where reality and fantasy were occasionally indistinguishable. Multiple narrator remains my storytelling technique of choice, as a reader and a writer.

The research for my novel Love And Other Thought Experiments formed part of my PhD on the overlap between philosophy and literature in the short stories known as “thought experiments.” The thesis was a study of the history and development of the story-cycle and the composite novel which overlaps in the way that philosophers, particularly philosophers of mind, create a narrative for an idea or theory. These thought experiments can become central to the conversation between philosophers, and new versions can be used as part of the response. In Frank Jackson’s thought experiment, What Mary Knew, for instance, the discussion continued into a book There’s Something About Mary. Not so much a sex-comedy, but certainly overflowing with jokes about what poor Mary could, or could not, be said to know.

Of course, the multiple narrator has many incarnations. There are collections of stories, alternate narrators, interwoven first and third-person narratives, epistolary novels, story-cycles, and composite novels. I am particularly absorbed by stories in which the multiple narrators offer alternate versions of the same event. While I have an undying admiration for Kazuo Ishiguro’s ability to tell a story with a single, unreliable narrator, as in The Remains of the Day and Klara and the Sun, multiple narration can give the writer access to a wider context and world view that can be equally helpful in communicating with the reader.

The beauty of the novel is its myriad forms and re-invention. You do not have to be an advocate of experimental fiction, or a member of OULIPO, to appreciate original ways of storytelling and be entranced when you find them.

In Love and Other Thought Experiments I wanted to explore the ideas of consciousness proposed in some of the most well-known thought experiments. I hoped to discover a convincing argument against the prevailing belief in the illusion of consciousness. The novel, it seemed to me, was far better at explaining other minds than any theory or equation. So I chose ten thought experiments, ten interrelated stories and characters, and threw all of life at them. The result was not what I expected or wanted, but it brought a kind of peace to my restless mind.

It is possible to think of every book is an experiment (though not a thought experiment) with multiple narrators: the author, the author-created narrator, and the reader’s own imagination. All these elements combine to tell the tale. Here are six of my favorite multiple narrator books.

*

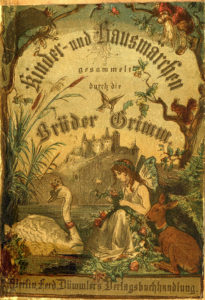

Grimm Brothers, Grimm’s Fairy Tales

(Canterbury)

These stories form a collection that share much with ‘improving stories’ and parables that emerged in Europe with the Age of Enlightenment. Each story is told by a different narrator but occupies the same imaginative space as the other narrators. Along with Hans Christian Anderson, Perrault, and Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books, these elevated much of my early-years reading and the excitement of library visits. Although linked by the qualities of magic and fantasy, these are less ‘Once upon a time’ and more weird and unsettling in their conclusions.

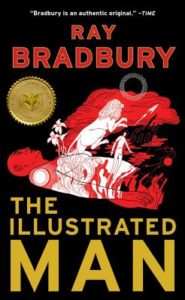

Ray Bradbury, The Illustrated Man

(Simon & Schuster)

This is a different kind of multiple narrator, multiple story, book, but unified by a single-voice. The illustrated man, a lone figure that the narrator encounters, is tattooed all over; the illustrations entrance the onlooker who recounts the stories he sees in the man’s skin. In the style of One Thousand and One Nights, collections or stories like these were very popular with early 19th-century and Victorian storytellers like Mary Shelley. The style was later adapted by science fiction writers, particularly from the ‘Golden-Age’ of sci-fi in the 1940s. Thus, we have the glorious Illustrated Man, and many others such as Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot. I gorged on such collections in my twenties, and they are still my great pleasure.

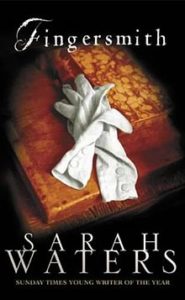

Sarah Waters, Fingersmith

(Riverhead Books)

Waters has perfected the historical novel with a twist with Fingersmith, a novel that employs alternating narrators. With echoes of Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White, Waters’ Victorian novel tells the story of Sue and Maud and the complex conspiracy that entwines them. Waters’ skill is in the visceral detail of the period that provides a background that, while evocative of the time, avoids pastiche.

Told in the first person, the alternating narrative is a satisfactory way of concealing and revealing information to the reader that is not available to the characters. Other alternating first person narrators include Wuthering Heights in which Emily Brontë uses two peripheral characters to tell the story of Heathcliff and Cathy, and An American Marriage, where Tayari Jones uses the device to examine the different feelings and experiences of the married couple Roy and Celestial.

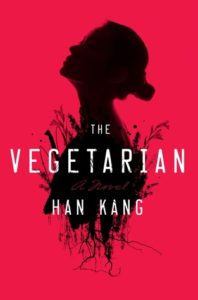

Han Kang, The Vegetarian

(Hogarth)

Told in three parts by three different narrators, Han Kang’s slender and disturbing novel uses first and third person narrative voice to tell the story of Yeong-hye a South Korean woman in contemporary Seoul who decides to become a vegetarian. Her subsequent transformation is narrated by her husband, her brother-in-law, and her sister who react with different levels of sympathy and understanding at Yeong-hye‘s deterioration. Interspersed with these interested parties, is the fragmentary voice of Yeong-hye and her dreams of blood and meat and slaughter, all connected to her guilt that she ever consumed animals.

The Vegetarian has a distinct three-part structure, and each part is a self-contained story. Other multiple-voiced narratives, such as Beatrice Hitchman’s All of You Every Single One, interweave the narrators to build more of a mosaic novel where the point of view may be wider, or inclusive of diverse perspectives such as David Mitchell’s Ghostwritten. Epistolary novels like Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ Les Liaisons Dangereuses and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple use the multiple narrator to great effect.

Haruki Murakami, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles

(Vintage)

While not strictly speaking a multiple-narrator novel, Murakami’s generous narrative diverges into many other encounters along the way. It’s a book that takes the reader into a simultaneously pedestrian and surreal world and invites you to experience the adventure in the manner of slow-boiled frog. I found the originality of the storytelling extremely liberating when I was writing Love And Other Thought Experiments, as though I had been given permission to escape from any particular laws. I love to put a book down and stare into space when I am reading, and Murakami allows plenty of opportunities for daydreams.

Jennifer Egan, A Visit From the Goon Squad

(Anchor Books)

A brilliant use of multiple narrators to form a mosaic novel based in the music industry. Comprised of self-contained short stories, like Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge, the book represents aspects of a world where characters or events may overlap non-sequentially. But whereas Strout’s creation builds a complete picture of a small community and its eponymous anti-heroine, Egan’s novel doesn’t form a single, unified narrative. In its place are drifts and eddies of stories whose individual delicacy produce a substantial landscape.

_______________________________________

Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward is available now from Vintage Books.

Sophie Ward

Sophie Ward is an actor and a writer. She has published articles in The Times, The Sunday Times, The Guardian, The Observer, The Spectator, Diva, and Red magazine, and her short stories have been published in the anthologies Finding A Voice, Book of Numbers, The Spiral Path, and The Gold Room. Her book A Marriage Proposal: The Importance of Equal Marriage and What it Means for All of Us was published as a Guardian short eBook in 2014. In 2018, Sophie won the Pindrop short story award for “Sunbed.” She has a degree in philosophy and literature and a PhD from Goldsmiths, University of London, on the use of narrative in philosophy of mind.