Mondiant Dogon on Writing as an Important and Difficult Healing Process

Jenna Krajeski Talks to Her Co-Writer and Author of Those We Throw Away Are Diamonds

The first time I met Mondiant Dogon was in the library at NYU where he was in his final year of graduate school. He had already written a draft of a memoir, a beautiful work about the unimaginable violence he and his family survived before living as refugees for decades, what Dogon calls a “forever refugee.”

We were planning to write a book proposal together—and, hopefully, a book—which would require a lot of conversation. We spoke for nearly a year before we finished the proposal, and over two years before finishing the book. We met in Dogon’s dorm lounge, after hours in the office of the tech startup where he worked, occasionally—as quietly as possible—in coffeeshops or restaurants.

During that first conversation, though, we barely spoke. Dogon showed me pictures, first of the green fields and forests near his childhood home in northeast Congo, then of Gihembe, the refugee camp in the steep hills of northern Rwanda, where he grew up. He showed me candid photos of his uncles playing mancala and portraits of him and his siblings before school. Dogon had been given the extraordinary opportunity of studying in the U.S., but most of the people in the photos were still living in Gihembe. He told me there was no point to him being so lucky if he didn’t at least try to help.

Since that first conversation—more of a viewing—Dogon’s goal has never changed. He still believes in the power of books to change lives, and his writing shows that. Over the years he opened up, and I had the privilege of being an audience to his extraordinary life story, told in two or three hours chunks in the evenings after he finished work. Our most recent conversation, below, was collected over a couple of weeks in a shared google document and occasionally fleshed out over the phone. I say “most recent” because we are friends now, and a conversation between friends never really ends.

*

Jenna Krajeski: When we first met you had a manuscript, about 70,000 words, about your life called Wounds of Dumb. I read it before we met for the first time and what struck me most, aside from everything you’ve been through, was the poetry and empathy in what you wrote. Clearly, you wanted to tell your story but you were also thinking about the language. When did you know you wanted to be a writer? And why did you start writing Wounds of Dumb?

Mondiant Dogon: I’ve known that I wanted to be a writer since I was in high school, but that realization was a surprise to me. It was really hard as a refugee to go to a Rwandan high school. We had to pass a national exam and then find funding to pay for school supplies, transportation, and room and board. When I was finally able to go I thought I would study math and science. Those subjects seemed the most serious to me, the kinds of subjects that helped you get into a university and get a job, in spite of being a refugee.

But in high school, I discovered books. I studied literature and I spent most of my time reading novels, plays, and poetry. On summer holiday back in Gihembe, my friends and I would practice writing and reciting poetry and when UNHCR had an event in the camp, I participated in poetry competitions. Sometimes I won and sometimes I lost, but at the same time I decided that I would start writing my own story.

I want [readers] to know what it’s like to be a refugee your entire childhood and to worry that you will remain a refugee your entire life.

I called my book Wounds of Dumb to show how the silence in refugee camps hurts and even kills my fellow refugees. We have so much inside of us but we don’t have the opportunity to let any of it out. We cannot freely express our thoughts, our emotions, or what we have been through.

JK: How did you manage to write the book? Did you use pen and paper? Did you have access to a computer?

MD: It was really hard to get resources to write in the refugee camp. I remember when I started primary school in Gihembe, we didn’t have formal classrooms or supplies. Instead of chairs, we sat on stones. In place of blackboards, two students held up a long sheet of paper for the teacher to write on. And instead of books and pens I used a broom bristle to scratch notes into my thighs.

For me, telling and writing my story over and over was a part of healing.

In high school I started writing poetry and Wounds of Dumb in small notebooks provided by UNICEF. When it rained our tent leaked and my pages would get soaked. When that happened, I rewrote it. I kept writing and rewriting like this until 2013 when I started at the University of Rwanda in Kigali and one of my professors lent me his laptop. It took some getting used to. I typed so slowly at first because it was my first time using a keyboard. I thought it would take a century to finish the book. But that’s when I really started to write Wounds of Dumb, on that laptop.

JK: What were your expectations getting your story read and your book published in the United States?

MD: I want to tell readers what is really happening on the other side of the globe in places most of them have never been and may never go. I want them to know what it’s like to be a refugee your entire childhood and to worry that you will remain a refugee your entire life. I hoped that by publishing a book with a big US publishing company I could reach many of those people. I wanted people to know my story and the stories of millions of people like me.

JK: When we first started working together, what were your thoughts on the interview process? Did it take a while for you to trust me?

MD: Before we first met, I read the book you wrote with Nadia Murad. I thought it was so moving, so I said, okay let’s work together.

The most difficult thing was building trust. Growing up in Gihembe I encountered a lot of discrimination because I was a refugee. I grew up with that stigma, and it was hard for me to trust the intentions of someone who wanted to know more about me. I was always ashamed of sharing my story. I assumed if people found out that I grew up in a refugee camp or that I had been recruited by rebels in Congo, they would only think the worst of me. It took a long time for us to build a relationship so that I trusted you enough to tell you both the good and bad in my life. Eventually we became great friends, and I stopped being ashamed.

I realized that my community needed to share their stories in order to heal the invisible wounds caused by war and violence. One way to do that was through art.

JK: We spent nearly two years meeting and talking about your life. Was there any part of the process that surprised you? Did it bring up any new memories? Were some things harder to talk about than others, and how did you manage those emotions?

MD: Yes, before working on the book together I had never shared the story of how my best friends Celestin and Patrick were murdered in Mudende refugee camp. That was a story I kept to myself. Everyone in Gihembe suffered trauma and most of us were survivors of the Mudende massacres. No one wanted to share those stories and make everyone feel worse, or relive it themselves. So I never wanted to burden anyone with the story of my best friends, even though it hurt to keep it inside.

After you and I started to build a bond, I was ready to share the story. But it was still very hard. That day I talked about Celestin and Patrick, I felt very emotional. After you left my dorm lounge at NYU I cried a little, which was unusual for me. I haven’t cried very many times in my life. But when we started working on the book I started crying more often. You’ll remember that sometimes I cried in the middle of interviews. We would have to take a break and start again when I felt better.

JK: I do remember that. It was hard for me to know when to stop asking questions, because I think you are very good at controlling your emotions and you work very hard and never wanted to tell me to stop or say no. But as time went on, you seemed to let your guard down. Do you remember how emotional you were when we first met with Ginny and everyone at Penguin? You said you had only cried like that a few times in your life which, considering what you’ve been through, is incredible. Why were you particularly emotional that day?

MD: I grew up in a place where war, violence, hunger and poverty were normal. It was almost like those bad things had their headquarters in Gihembe. I had seen so much since I was three years old and I learned early on that tears do not change your circumstances. But working on the book and telling my story in order to reach people maybe could change something.

So when I met Ginny and everyone at Penguin and it became clear they weren’t judging me, and instead that they were genuinely interested in my story and wanted to help me tell it, I became very emotional. Tears ran down my face because I was finally able to tell pieces of my story that I had never shared with anyone before. I was very emotional to see my dream come true, after working on the book for so long and never knowing if anyone would read it or care.

JK: Telling your story requires reliving it. Overall, was the process of writing the book good for healing your “invisible pain”? Or was it more painful than you imagined?

MD: For me, telling and writing my story over and over was a part of healing. It took a long time to get to that point, though. At the beginning, I felt like every time I shared my story would have to be the last because it was so painful. But after a while working on the book helped me get rid of all the negative things I’ve carried around my entire life. Now I can say that my shame, trauma, depression, and loneliness is much less than it once was. I feel like I can embrace positivity because I look at my life and my experiences through a lens of healing.

JK: You spent some time before leaving Rwanda traveling from refugee camp to refugee camp collecting stories. Why did you choose to do that? What are some of the most powerful stories you remember?

MD: After I graduated from the University of Rwanda in Kigali, I realized that my community needed to share their stories in order to heal the invisible wounds caused by war and violence. One way to do that was through art, writing down and talking about what we went through and what we want for our future. At that time, nobody was asking us to tell our stories, including UN agencies.

I decided to do it myself. I went from camp to camp in Rwanda, first building a bond with other refugees so they would trust me enough to share about their lives, and then collecting stories of war and rape. Most of these stories were shared by women. They told me they had never told anyone about what happened to them, not even their own families, even though some of them had even given birth as a result of being raped.

In Nyabiheke, a refugee camp in the northeast of the country, I met a woman who was raped during the war in Congo and was impregnated by her rapist. She had never told anyone before me, not even her own children, because she felt too ashamed. I was amazed by her courage. Another woman walked twenty-five miles every day to a village where she was paid one dollar to wash clothes, all so she could afford to send her children to school. These women are not just victims of war. They are not just refugees. Their strength and resilience is a lesson to everyone.

JK: Part of your book is about silence—refugees not being heard, not telling their stories, not articulating their pain. I remember you saying that some of your friends at NYU never knew you were a refugee. Are you worried how they might react when they read the book?

MD: Jenna, to be honest with you, I was very anxious at the beginning. It’s normal to feel that way when you start something new. I didn’t know how my community and my parents would react when they learned that I planned to publicly reveal things that other Bagogwe never wanted to say out loud. But I knew that sharing my life experience and everything my community and I went through will be an important part of healing from trauma and can lay the foundation for new stories about what the future holds.

JK: Have your family and friends read the book? What do they think?

MD: My brothers and sister read the book. They are in it, of course, so I wanted to make sure they were okay with everything I had written. My parents don’t speak or read English well, so my siblings and I explained to them what was in the book. A couple of my friends also read the manuscript. I was worried about what they would think, but their feedback was all positive. They said they were grateful that I was sharing these stories.

JK: Today people talk about a “refugee crisis.” And very recently we’ve seen tens of thousands of people fleeing violence in Afghanistan, and Haitians being met with violence at the border with the U.S. How do you feel when you see these news stories? Do you feel connected to these people?

MD: Their stories are very similar to the journey I took in 1996 when my family and I fled Bikenke, my home village in Congo, and my journey in 2005 when I returned to Gihembe from Congo where I had been recruited by rebel fighters. When I see any refugee or migrant being forced to leave their homes and risking their lives to find a new place to live, I remember how those journeys I took were full of fear and danger, and that they started with the hope for a better future. I think in a globalized world, we all share responsibility to help. I live in New York now, and one day I hope to be an American citizen. As Americans, it’s our turn to welcome, integrate and support these communities that fled their countries for better life.

JK: What’s the main message of the book? What do you hope people will learn by reading your story?

MD: I want to change the way people look at refugees. I want to show the world how smart, hopeful, courageous, ambitious, empathetic and kind refugees are, in spite of the war, violence, trauma, dehumanization we encountered growing up in refugee camps, and the cruelty of having to become an adult too quickly. For people like me and my loved ones who are at risk of living our entire lives in refugee camps, I wanted to remind the world that we are still here. We still exist, and we deserve to be heard.

_______________________________________________________

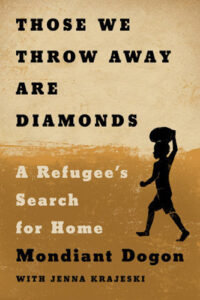

Those We Throw Away Are Diamonds: A Refugee’s Search for Home by Mondiant Dogon with Jenna Krajeski is available with Penguin Press.

Jenna Krajeski

Jenna Krajeski is a reporter for The Fuller Project whose writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, and The NationThe Last Girl, and was a Knight-Wallace Fellow at the University of Michigan.