Sonja’s sitting in Folke’s office. It took a long time to get here, as she kept taking detours. She’s been through Frederiksberg Gardens, and she walked down Gammel Kongevej and then back again before taking the side street where Folke’s Driving School is located. It’s five now; she wanted to catch Folke in the narrow window between when Jytte goes home and when students show up for theory. She’d been standing in line outside the office for a while. There’s almost always someone in there with Folke. The youngsters inevitably forget their money and signatures, and the suspended drivers prefer to bring their shame at odd hours, so she feels like a camel looking for a needle’s eye to slip through. But now Sonja’s seated on the chair across from him. She’s asked if they might speak in confidence, and Folke’s closed the door.

“I can’t change gears,” Sonja says, even though that wasn’t what she wanted to start by saying.

“I see,” says Folke. “What exactly’s giving you problems?”

“Everything. Or rather, it’s mostly just Jytte.”

“Jytte?”

“Yeah, I’m sure she’s a good teacher for the younger students. But for an old person like me, I don’t think she’s a very good fit.”

Folke’s leaning over his desk. He’s a tall man with a bald pate and a striking beard. His face is alive, open, and he’s made a concerted effort with the beard. From his chin it tapers to a point, but elsewhere it’s thick and bushy. It’s as if the hair he once had atop his head has slid down under his chin, where it now points toward his other male hair. He extends his legs under the desk. They’re long, and his driving-instructor gut bulges out beneath his hooded sweatshirt. Folke resembles a fat stork when erect and a happy pagan Viking when seated. Or else he looks just like himself, and Sonja likes that.

“What’s wrong with Jytte? Is it her big trap, or what?”

“It’s more that she loses her temper. She won’t let me shift gears, and how am I supposed to learn, then? I get so exhausted when I’m out driving with Jytte that I have to go home and lie down on the couch. And the lessons do cost money.”

“Jytte’s got a mouth like a longshoreman and a heart of gold,” Folke says, leaning back. “You shouldn’t take her so seriously.”

“But then there was the brawl.”

“Brawl?”

It’s now or never. So out comes the story of the cross-cultural encounter in the intersection by Western Cemetery. Sonja remembers to include the detail about how Jytte used the horn. The fear, the adrenaline, the hotheaded outburst; the complaints about wrecking Jytte’s car. Everything. Folke must be told, and he sits there with his face in worried furrows. He looks like someone who’s listening to Sonja, and though she hasn’t really thought that far . . .

“I want to drive with you instead.”

Folke runs his fingers over his impeccable beard. He explains that he doesn’t really drive with that many students anymore. He takes care of theory and administration. He’s also hardly at the school when it’s convenient for students to drive.

“But I translate Swedish crime novels,” says Sonja.

“I don’t get it.”

“What I mean is that I’m my own boss, in a sense. So I can drive whenever it suits you.”

Folke doesn’t hesitate an instant but smiles and opens a drawer. Inside is his calendar.

“Let’s do that, then, and don’t you worry about Jytte. I’ll call her. Don’t get your head in a twist. It’s my business, my responsibility. I’m going to teach you how to shift gears.”

“It’s the embrace; it was a smidge too intimate, yet pleasant at the same time. It caught her napping. Now she doesn’t know how to comport herself, and her cheeks are prickling.”

Sonja’s on the verge of tears. It happens unexpectedly; the sob sits in her throat and wants to come out. Folke’s hands move efficiently from side to side across the desk, and she longs to grasp one of them. Squeeze it, say “Thank you,” from the heart. It doesn’t escape Sonja’s notice that she gets red in the face, because this sort of thing rarely happens. It almost never happens anymore—that someone wishes Sonja the best. She’s used to dealing with everything herself, and she’s reasonably good at it too, but that Folke would reach down in his drawer and face the heat—Sonja hadn’t expected that. It isn’t that she’s planning on the emotion to lead to anything. She isn’t. The idea behind getting a license isn’t at all to find someone to drive for her. On the contrary, and besides, she’s heard that Folke’s married to a doctor. She doesn’t understand how he pulled that off. But he’s married to a doctor, and that’s a good sign, Sonja thinks, and now he’s looking up at her and smiling.

“Crime novels, you say? Did you translate the Stieg Larsson books? They’re great. Or that guy Gösta Svensson? My wife’s nuts about Gösta Svensson.”

Sonja opens her mouth. Her skin stops glowing, but she can’t manage any more than that. Folke gives her a yellow note with a date and time for her next driving lesson.

“It’ll be Thursday, then.” He smiles. “And I’ll take care of Jytte. You just go home now and rest.”

Then he’s towering over her, there in the driving instructors’ office. He’s taller than Sonja, standing before her in his hoodie.

“Come here!” he says, opening his arms.

Sonja disappears into Folke’s arms, his arms like a father’s pressing her to his chest. She cannot speak, as she’s on the cusp of crying. She also feels bashful. And she hasn’t answered about Gösta, but now the moment’s passed, and Folke’s pushed her away again.

“Thursday,” he says.

“Thursday,” she echoes, and she decides to take a couple of Gösta’s books along when they see each other next.

Then he’ll be happy, and so will his wife. Then the lines will be clearly drawn. Then no one will get confused out in the car.

It’s the embrace; it was a smidge too intimate, yet pleasant at the same time. It caught her napping. Now she doesn’t know how to comport herself, and her cheeks are prickling. She feels like a confirmand, and there’s a line outside the door waiting to come in. A long line of youngsters with course papers and passports. Folke lets the door stand open and asks them to move closer, closer. Sonja oats through the theory classroom, painted royal blue. She can smell Jytte in the furnishings, and it won’t be long before Jytte knows that Sonja’s ditched her for the boss. It won’t sound pretty. Then she’ll let Sonja have it with both barrels. Then it’ll come out that Sonja was never approved by the medical officer, and she claims it’s something with her ears, but you can bet it’s something else.

Something else?

Sonja steps out onto the front steps and into a cloud of cigarette smoke. The rougher students stand around, grabbing a smoke before class. Jytte does the same when she’s there during the day, but right now one of the students is describing a driving lesson. The student demonstrates how she turned the wheel too fast. It’s an exaggerated movement, and Sonja has to duck quickly to avoid being struck by her cigarette. And in a flash it’s there: the positional vertigo.

It’s triggered by the dentist position and by bending over too fast, and Sonja has to grab hold of the banister while she restores her head to its proper position. When she gets her head back into place, the world rights itself. The world’s where it should be, but it’s been shaken. Sonja takes a couple of steps out onto the sidewalk. She doesn’t want any of the smokers to see that anything’s wrong, and after all, it’s not the dizziness itself that creates a problem for driving. She’s able to orient herself just fine, as soon as she gets her head out of the angle that triggers the episode. It’s more that, for the next couple of hours, she’s a tad out of focus. That’s not so great in an automobile, but then again it could be worse. And her grandmother could drive a car; her mother too. The first time that Mom got dizzy, she went to the ear doctor, and he had her lie on the examination table and rolled her head around. That triggered a violent attack. Mom’s eyes centrifuged and her hands clawed the air while the doctor held her down. He told her she had to lie there a few minutes and “just let the stones settle down.”

“There was a long period when she thought she’d escaped the vertigo. For a while she even imagined that moving to Copenhagen had made a difference. That the dizziness was something social, almost a tradition, she supposed, that you could break with.”

That helped for a time, but then of course the dizziness returned. It returned when Mom hammered her head against the car’s doorframe on the day Kate and Frank were getting married. This was in the parking lot up by the church, and thank God they’d arrived there good and early. Mom got Dad to drive her home with the excuse that they’d forgotten something. Sonja wasn’t aware that anything was up, but that might have been due to the dress Kate had stuffed her into, tubular and lemon yellow. Meanwhile, Mom thought she could take care of the positional vertigo herself. Surely the maneuver the doctor had used on her could be performed at home, she thought. She removed the cloth from the dining room table, then took a running start and leapt up on the table so she’d land on it prone, with her head tilted back slightly. The tricky part was catapulting her body up there just right. If she failed, she’d smash her head on the tabletop. Or worse, she’d continue over the table and onto the floor on the far side. But if she succeeded, she’d just have to let her head loll backward over the edge of the table. So she took a running start in her heather-colored dress and lifted herself onto the table, landing perfectly. Dizziness assailed her “but the stones had to settle,” she explained as she stood in the church later and watched Kate walk up the aisle toward Frank.

Sonja’s advanced a cautious distance down the street. Since she’s no longer visible from Folke’s Driving School, she sits down on some steps. There was a long period when she thought she’d escaped the vertigo. For a while she even imagined that moving to Copenhagen had made a difference. That the dizziness was something social, almost a tradition, she supposed, that you could break with. But then one day she was standing in the entry of her at and went to tie her shoelaces. The moment she bent over it hit her—the positional vertigo. She crashed into the doorframe and on out to the kitchen and into the stove, before she finally got herself situated so that the fridge stopped moving.

The disorder, she’d thought, and went to see the ear doctor, who proceeded to sling her around. “It’s not dangerous, you know,” he said on cue. “It’s just some tiny stones inside of you that are breaking free.”

And the stones just had to settle into place.

Sonja would like to remain sitting there till the sensation of being knocked off course subsides. What she’s done for herself is a good thing, isn’t it, even though she’ll have to get past Jytte now. Sonja’s going to be gasoline on Jytte’s flames. The smallest hint of a problem with Sonja, and Jytte will set the medical officer on her. If it were up to Jytte, Sonja would never be allowed to learn to shift. She wouldn’t even be allowed to drive. She’d be deprived of her right to . . . yes, to what Sonja doesn’t really know, but in any case it involves some sort of right, flickering in the back of her eyes like a faulty fluorescent light, and she pictures Mom in a gym suit. The gym suit is shiny and blue, and Mom’s feet move swiftly; she’s the star of the team. She can do a kick split and spin like a top. She’s so stunning that Dad can’t take his eyes off her. No way he’d ever get enough of watching a girl like that. Dad takes a running start, he takes a running start and streaks through the gym, his big hands stretching out before him. He wants to get over to where Mom is, and he does. He comes within reach of the girl in the shining outfit. She looks like a kingfisher, he thinks, and kingfishers are rare. They screech as they fly through the air like arrow shafts, and Mom screeches too when Dad’s red hands grasp her about the waist. Then she sinks down; he is gravity itself. “You’ve got strong arms,” she tells him.

And he did, Sonja thinks, lifting herself up off the steps. Strong arms and good sperm quality, and here stands Sonja, in the middle of the great wide world.

She’s feeling better, so now she’d like to walk home slowly. She walks down Gammel Kongevej so quietly that she comes to a standstill before the window of a hair salon. Placed in the window are two decapitated heads, a woman’s and a man’s. They haven’t had a change of wigs since the mid-eighties, and the frames of their glasses look creepy. Somewhere behind them, a woman with a silver-tinted perm walks about cutting hair. She’s put coffee in front of her customer. The gown’s a florid orange, and Sonja can see that the stylist is chatting. Her scissors are busy and so is her tongue. There are two days till Thursday. Two days till Folke’s going to teach Sonja to change gears.

Is he going to hug me every time we go out driving? she wonders. Must I really get more than I bargain for in every single store?

__________________________________

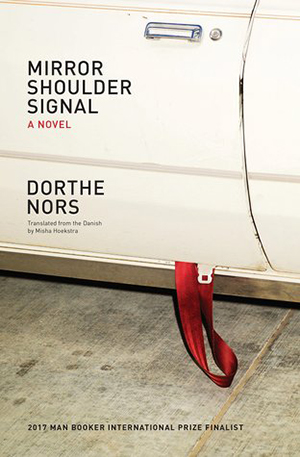

From Mirror, Shoulder, Signal. Used with permission of Graywolf Press. Copyright © 2018 by Dorthe Nors.