He was, I remember, short, but by no means conspicuously short, and of a bright, almost juvenile complexion, very active in his movements and garrulous—or at least very talkative. His judgements were copious and frequent in the old days and some at least I found entertaining. At times his fluency was really remarkable. He had a low opinion of eminent people—a thing I have been careful to suppress, and his dissertations had ever an irresponsible gaiety of manner that may have blinkered me to their true want of merit . . .

–H. G. Wells, Select Conversations with an Uncle, 1895

*

Few who knew him could doubt that H.G. Wells was enjoying a moment of self-mockery in the introduction to his first book for John Lane, publisher of the 1890s most associated with Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, the Yellow Book and other aesthetic icons. Wells first came to readers’ attention in the Pall Mall Gazette as a witty writer of belles-lettres and imaginative short stories. This reputation encouraged the influential writer and editor W.E. Henley, much-loved original of Stevenson’s Long John Silver, to commission a two-part novel for his New Review based on Wells’s already published theory that time was the fourth dimension of space. Wells was elated, especially since he needed the money, and he burned so much midnight oil writing his story that his landlady considered charging him extra for her over-used lamp.

Time-travel stories were by no means unfamiliar to Victorian audiences. Edward Bellamy’s narrator fell asleep and awakened after about 120 years to review our future as his past in Looking Backward (1888). Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) went back to the court of King Arthur via a blow on the head; Edwin Lester Arnold’s The Wonderful Adventures of Phra the Phoenician (1890) proceeded through time by a process of reincarnation, while the popular fantast F. Anstey in Tourmalin’s Time Cheques (1891) used the idea of time travel for comic effect. Wells’s great predecessor both in scientific speculation and social satire, Grant Allen, in “Pausodyne” (Belgravia Magazine, 1881) created a chemical capable of inducing a kind of suspended animation, allowing its tragic inventor to travel involuntarily from the late 18th century to the 19th. Earlier travelers had merely to fall asleep, like Rip Van Winkle, to wake up centuries or millennia hence.

In spite of all this, and his own modest claims for not being the originator of the idea, Wells’s The Time Machine stands out immediately as something different. First he gave time at least a quasi-scientific quality, but most importantly the novel is about the actual mastery of time, as we had already mastered geographical space. Unless something went wrong with his machine, Wells’s time traveler was able to move himself more or less accurately to any desired period of the past or future, exploring time as Livingstone had explored Africa.

When the serial appeared in early 1895, the story became a talking point. W. T. Stead’s Review of Reviews called Wells a man of genius, while writers like Thomas Hardy, Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Ford all celebrated his originality and talent. The book was quickly satirized in Punch and elsewhere. Wells became an extraordinary exponent of what was called ‘the New Writing’. His vision of the end of the world was echoed in the millenarianism of the late 19th century, whose magazines were full of articles like John Munro’s “Is the End of the World Near?” in Pearson’s Magazine. It found resonance with the younger generation as well, who 20 years later linked it to the bleak existential atmosphere of the trenches.

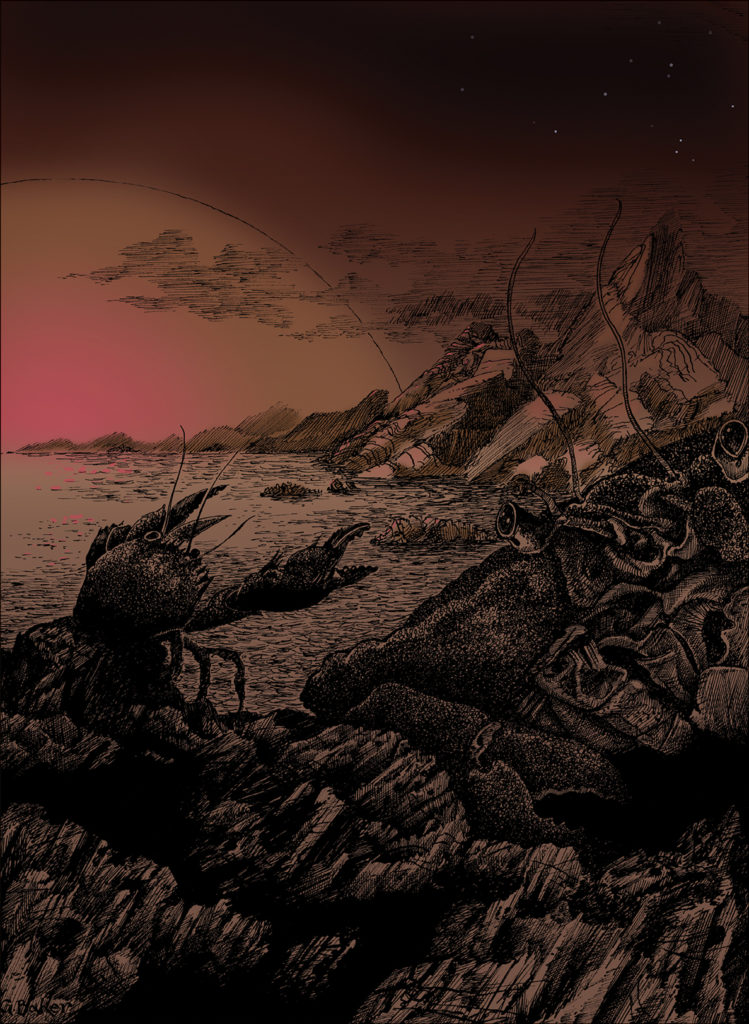

By Grahame Baker-Smith

By Grahame Baker-Smith

The book is surprisingly modern and, indeed, is discussed as a modernist text by Daniel Albright in his catalogue essay published for the Make It New: The Rise of Modernism exhibition (Harry Ransom Center, Austin, Texas, 2003). Albright remarks on the book’s cinematic qualities:

Wells’s fable is profoundly cinematic, in that it was perhaps difficult to conceive such a thing as a time machine until the invention of movies, where a continuous time-segment attains spacial definition in a reversible strip. When the narrator of The Time Machine starts to move forward in time, he sees a sort of stroboscope effect of day blinking into night, as if he were watching a poorly-projected film. In the distant future he finds an ape-like race of troglodytes, the Morlocks, as if the human race had been busy devolving over several hundred millennia. It seems to matter little whether the unspooling reel of human history is played backward or forward: the future and the past look rather similar . . .

Albright also sees the book as something of a commentary on the aesthetes in whose company Wells found himself as a contributor, for instance, to the Yellow Book, and adds:

The Time Machine is a horror story as well as a bio-economic theory. It turns out that the Eloi are “cultivated” in two senses of the word, for the Morlocks raise them for food. Decadence begins by running “to art and to eroticism, and then comes languor and decay.” Wells imagines a future in which white chimpanzees feast on the corpse of Oscar Wilde. This sort of abutting of the too-coarse and the too refined is common in modernist art.

With Conrad, Ford, Gissing and a few others, Wells represented the first real flowering of modernist ideas which were to reach their full potential in Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, where original style and method would marry with vision. It is possible to see the intimations of The Time Machine realized in the early work of Pound and of Eliot (while Mauberley, Prufrock and Polly are cousins, at least). What impressed Wells’s contemporaries was the freshness, the modernity of his language, which was very much at odds with the affectations of the fin de siècle, exemplified by the likes of Richard Le Gallienne. If a little hasty, it was a literary language, aimed in these early books at peers and friends like Arthur Morrison, W. Pett Ridge, J. M. Barrie, Jerome K. Jerome and Arnold Bennett, as well as Henry James and George Meredith, who all praised the book.

James greatly admired him both as a writer and as a man (“What a brick Wells is,” he exclaimed on hearing how H. G. had rushed to Spain to be with the dying Gissing). Only later would Wells hurt James badly in the satirical Boon (1915), writing as ‘Reginald Bliss’, in which he would break with his literary peers, lampooning James in the process, and begin to address “the common man” in the kind of populist declamatory intimacy which became his trademark and was adopted by the likes of J.B. Priestley, whose own “time” plays owe as much to Wells as they do to J.W. Dunne and Ouspensky.

Most importantly [The Time Machine] is about the actual mastery of time, as we had already mastered geographical space.Wells joined the Fabians in 1903, but he was already on his way to being a convinced socialist. His ideas about the future of capitalism are, of course, thoroughly reflected in his depiction of the Eloi and the Morlocks, amongst whom the main adventure takes place. In some ways his social commentary is the least interesting element in the book. Wells’s penchant for “futurism,” for issuing warnings about Things to Come as a popular oracle, gradually worked against his creative instincts. Indeed, his career, though continuing to be far more interesting and vital than is conventionally held, turned a corner around the time of the First World War, as if he recoiled from seeing his darker visions take shape before his eyes. Perhaps in rejecting literary ambition in favor of being a popular seer, he was trying to escape the implications of his own creative gifts.

The sheer visual power of Wells’s early novels is greatly reminiscent of Bunyan and Blake. His literalism increasingly countered his visionary gifts, but in 1895-6 he was decidedly running on instinct. He had no time for contemplation or escape. Like The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau was written at white heat in a very short space of time. Moreover, in the year between the appearance of the two books he produced a substantial volume of short stories The Stolen Bacillus, his charming cycling fantasia The Wheels of Chance (where his familiar “common man” was first introduced), The Wonderful Visit, an angry satirical comedy in which an angel comes down to Earth (it has much in common with Grant Allen’s The British Barbarians, 1895), and a considerable amount of journalism and magazine fiction. He was supporting a new wife and her mother and he was determined to break out of the miserable semi-poverty he had known before the appearance of his first novel. He believed his “one idea” would make his name, and he was right.

By Grahame Baker-Smith

By Grahame Baker-Smith

It could be that this idea, of time as the fourth dimension of space, led Wells to wonder about evolution itself and how it could be accelerated in some way. It’s unlikely that he made much of a conscious leap from the Morlocks of The Time Machine to the creatures found by Edward Prendick on Doctor Moreau’s remote island, for at this time Wells was evidently driven far more by inspiration than by rational speculation. Yet “vivisectionism,” operating on animals for experimental purposes, was very much a cause célèbre of Wells’s liberal contemporaries, and his Darwinism caused him to speculate further about the means of controlling human development as well as mastering time. He was drawing on a dark and daring imagination which gave form to the fears and yearnings of a generation witnessing the same kind of rapid social upheaval as our own, its hopes as well as its fears linked to science. The Time Machine with its extraordinary descriptions of the end of the world, its unsentimental picture of a future in which human beings are reduced to their most extreme characteristics, had a tremendous impact on its first readers and to this day has lost none of its effect.

That work is visually more powerful and original than his later work, when he began to value his intellect over his natural talents and come up with suggestions for social engineering which weren’t present in his first novels. As Wells was sought out by newspapers and the public to predict the future, he moved further away from the inner self which had given him his earliest nightmarish visions, with the result that he became less and less accurate at capturing the psychic tenor of his times and echoing them in his fiction. It is perhaps ironic that he was always more accurate in fiction than in non-fiction.

In his early fiction he displayed a knack not only for seminal ideas but also for exemplary characters. Like Mr Hyde, Dorian Gray or Count Dracula, Doctor Moreau was an original who was often imitated, although he himself bears something in common with Victor Frankenstein in his pursuit of a scientific obsession which proves finally self-destructive. While he lacks the personality of later Wells characters, like Bert Smallways, Mr. Polly, Kipps, or even Griffin, the Invisible Man, he registers nonetheless as a prototype. Albright’s reference to the cinematic qualities of Wells’s early work is reflected in the enthusiasm with which it was produced for films. The best version of Moreau, released as The Island of Lost Souls (1933) starring Charles Laughton, Bela Lugosi and Richard Arlen, with a script by “the American Wells,” Philip Wylie, remains a masterpiece of dark suspense. It was followed in the same year by James Whale’s brilliant The Invisible Man, starring Claude Rains, with Wylie once more as co-writer. Again rather modestly, Wells claimed that the films “saved” his two books from obscurity. These films, perhaps more than the novels, do show how Wells’s work linked to predecessors like Mary Shelley (also writing at a time of considerable social upheaval), and emphasize the Gothic qualities of his early fiction.

By Grahame Baker-Smith

By Grahame Baker-Smith

Doctor Moreau is a particularly strong account of the Frankenstein theme, of man’s tampering with the power of nature and its likely consequences. In these days of tomatoes with embedded fish genes, cloned mammals and other examples of genetic engineering, the rationale Moreau offers for his experiments also has horrifying echoes of Dr. Mengele and his fellow Nazi doctors who performed vivisection on living, unanaesthetized human beings. In fact there is much foreshadowing of the Nazi terror and many of the narrator’s remarks have uncanny significance to our post-holocaust generation:

The crying sounded even louder out of doors. It was as if all the pain in the world had found a voice. Yet had I known such pain was in the next room, and it had been dumb, I believe—I have thought since—I could have stood it well enough. It is when suffering finds a voice and sets our nerves quivering that this pity comes troubling us.

While Moreau’s justification for his work also strikes a more-than-familiar chord:

‘You see, I went on with this research just the way it led me. That is the only way I ever heard of research going. I asked a question, devised some method of getting an answer, and got—a fresh question. Was this possible, or that possible? You cannot imagine what this means to an investigator, what an intellectual passion grows upon him. You cannot imagine the strange colourless delight of these intellectual desires. The thing before you is no longer an animal, a fellow-creature, but a problem. Sympathetic pain—all I know of it I remember as a thing I used to suffer from years ago. I wanted—it was the only thing I wanted—to find out the extreme limit of plasticity in a living shape . . . To this day I have never troubled about the ethics of the matter. The study of Nature makes a man at last as remorseless as Nature.’

In some ways the arguments of Dr. Moreau make this novel even more a modern book than its predecessor. Wells raises questions which, in a variety of writings, from essays to further fiction, he attempted to deal with all his life. When the realities of the Nazi holocaust were revealed in his final year, he wrote his moving testament Mind at the End of Its Tether (1945). Reason had failed to save us. The uncertainties of his earliest years returned with a vengeance. The handle he thought he had on the world, when he went to Russia and met Stalin, was the guest of presidents and kings, was asked to speak and comment on every subject under the sun from “the Jewish Question” to eugenics to space travel, proved an illusion.

By Grahame Baker-Smith

By Grahame Baker-Smith

In these two early books Wells gave shape to his own and his contemporaries’ anxieties and concerns. He brought a moving lyricism to his vision of the end of the world, just as he brought a harsh realism to his fantasy of vivisection and physiological engineering. Both visions were convincing to his thousands of readers who made The Time Machine one of the greatest bestsellers of the last century, as a recent New York Times feature showed, ultimately outselling even Stephen King and J. K. Rowling, and having a far more lasting effect on our common psyche. The Time Machine defined the way Edwardians saw the future, just as Nineteen Eighty-Four defined the popular vision of the 1950s, 2001: A Space Odyssey defined that of the 1960s, and Blade Runner and The Matrix define how the early 21st century perceives its future. Every book, film and play which thematically followed The Time Machine and The Island of Doctor Moreau was in some way colored by them. Every author who considers writing a time-travel story must look first to Wells. Wells has been acknowledged directly or indirectly in many books, even becoming a character in other time-travel fiction. Moreau lives on in the work of such authors as Alan Moore. Moore most wittily included Moreau in his enjoyable postmodernist riff on seminal Victorian and Edwardian popular fiction The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, a graphic novel in which the obsessed doctor has returned to reside in rural England, creating monsters who closely resemble such beloved anthropomorphic characters as Pooh, Peter Rabbit, Tiger Tim, Rupert Bear, and Toad of The Wind in the Willows, a sardonic commentary on that rarely examined side of English children’s fiction which I suspect Wells would have enjoyed and rather envied.

It is a measure of Wells’s genius that his vision and his characters can be reinvented again and again and lose none of their original power. The two tales can themselves be reread constantly and continue to engage us, to horrify us, forcing us to reflect not only on our human capacity for good and evil but on the shape of many things to come.

Wells spent much of his career attempting to escape the bleakness and seeming inevitability of his early predictions, seeking more cheering and positive futures, ways of controlling the worst aspects of human nature. But history caught up with him by 1945 and, whether he wanted it or not, vindicated his younger, visionary self. He was a man in perpetual dialogue with himself. His best books, as V. S. Pritchett points out, describe a story of optimistic outward journey and chastened return. That Wells’s life should also reflect that circular journey is an irony he would no doubt, in his more cheerful moments, have appreciated.

__________________________________

From the introduction to The Time Machine & the Island of Doctor Moreau. Used with the permission of the Folio Society. Introduction copyright © 2019 by Michael Moorcock. Illustrations by Grahame Baker-Smith.