MFA vs. MBA? Finding Unlikely Literary Inspiration at Harvard Business School

Isabel Yap on Learning the Art of Storytelling Where She Least Expected It

On a hot day in August 2018 I put on a full suit—black blazer, black slacks, and Mary Janes, because I didn’t want to spend the day teetering on pumps—and walked to the newly-opened Klarman Auditorium for the opening remarks of my first day at Harvard Business School. I had moved to Boston the week prior and was still acclimating to dorm life, on the East Coast, surrounded by the most alarmingly successful young professionals one could stuff onto a campus.

It wasn’t that I felt impostor syndrome, exactly. I knew what I’d done to get there, but I also knew so much of it was luck; I’d been accepted on my second try despite little changing in my profile. Mostly I felt curious. Like some part of me was perched, with a recorder and notepad, eager to capture everything for future use. I found a seat and made small talk with those around me, regurgitating my resume until the program began.

We were told that the next two years would be among the most amazing and fulfilling of our lives. We would meet our best friends, expand our horizons, and undergo a transformation. Attending an MBA meant being “broken apart and put back together, but in a good way.” You would question everything about your life and ambitions, but after this ordeal you’d have greater clarity, or at least, a better sense of yourself “as a leader.” That was the school’s mission, after all: to educate leaders who made a difference in the world.

I felt like a whole person already, so it was strange to be spoken to as if I weren’t. School had been a deliberate choice, a calculated tradeoff. Still, in the burbling air of that auditorium, anything seemed possible: no hope nor dream was barred from us, but even as I clapped in dutiful agreement, I felt my shields go up. Ah-ah, I thought. Some dreams, you mean.

*

Reasons why I pursued an MBA:

1. I’d been promoted at work and felt keenly the limits of my influence, my inability to break down strategic problems.

2. My grandparents had always encouraged us to study hard, so with minimal prompting I staked my entire childhood identity on academic success. They did not live to see me graduate summa cum laude from college, but years later—even after I realized I disliked the me who judged people based on where they’d studied—I couldn’t shake the desire to do this, at least, for them.

3. Growing up, I was obsessed with two things: words and money. My first love was books, and English was my favorite and best subject; at school I was known as “the writing girl.” But from the moment I had an allowance I was obsessed with accumulating cash, recording every debit and credit in a little notepad. I craved financial independence from before I knew the term, and was determined to make a good living.

That I loved writing so much, then, posed a challenge. I wanted to write, but I could not imagine writing consistently enough to put food on the table. There would be no audience to sustain it. My writing was too niche, too weird, too Filipino.

This wasn’t something my parents told me. They never discouraged my writing, never dissuaded me from a creative path, like I know other Asian parents do. They didn’t need to. I did that to myself, with a chilly certainty: This dream was impossible. If I insisted upon this impossibility, I could spare myself the pain of hoping. Anything that proved otherwise would be a little bonus.

This was not such a strange thing to think. Back in Manila, I had no models for what a writing life could look like. The bookshelves in my school library, the window displays in our bookstores, were filled with foreign authors. Whenever I had the luxury of purchasing a book, I too purchased a book by a foreign author.

Even after I started having some writing success, these feelings persisted. I took the work seriously, but I could not bear to want it more—which meant, of course, that I wanted it after all. I sold a story or two each year after graduating from the Clarion Workshop, the same year I graduated with a business degree. Those story sales could not cover a single month of rent. Meanwhile, in my tech career, I could be hardworking and strategic in a way that got predictable results: a promotion, a salary raise.

If writing is what I want to do, why shouldn’t I do it? This diary page was folded in half, with MFA vs MBA scribbled on top. Why not focus on writing now, instead of waiting for some ideal future where I can write?

Because writing won’t feed me, I wrote. Because it’s not enough.

*

Harvard Business School is a program that privileges stories. Almost every subject is taught via the case method. A case is a 10- to 30-page article summarizing a business dilemma in the form of a story. Ask any student, and they’ll cheerfully parody a typical case opening: John Smith (HBS ’98) stared out the window of his Manhattan high-rise. He was stressed. He didn’t know if he should invest in more widgets or kill the widget program entirely, and his board wanted a decision by tomorrow . . .

Cases are debated for 70 minutes. As a student, you learn to find your timing, the moment when you actually have something to say. Your hand must shoot up at the precise point in a professor’s counter-clockwise turn when their eyes land on you. Miss that moment, and you’re doomed to spend the rest of the class searching for another opening. The case method endures through students’ willingness to self-disclose and teach each other. No one can test out of classes. Thus, a CPA must take accounting, and a private equity whiz must endure our bogus justifications for DCF projections.

We each had a role to play. The MD/MBAs used their medical authority. Consultants were fond of three-point statements. As for myself, I quickly learned the perspectives I could bring into the classroom: I was a start-up person, from an actual start-up people had never heard of. I was a female in tech—still strangely novel. (We did the Google gender discrimination case twice.) I was bi, and spent half the semester thinking I was the only queer woman in my section; happily, I was mistaken. I was an immigrant. I was Filipino. Any of these could be brought into the discussion and leveraged at the right moment.

That I loved writing so much, then, posed a challenge. I wanted to write, but I could not imagine writing consistently enough to put food on the table.I was, and am, a writer. But that didn’t play into my classroom utility, so I mostly left it out. I wasn’t hiding it. It was my day one fun fact: Hi, I’m Isabel, and I write fantasy and horror stories. Once, I shared a sweet email I’d received from a reader, and thereafter was introduced to new people as, “This is Isabel, and there’s a national holiday celebrated for her in the Philippines.” It was only a celebration for that one student, at her school, but no amount of clarifying could disabuse the notion that I was famous. It was embarrassing and touching. I had won no awards, had neither book deal nor agent, but my classmates, in their earnest astonishment at the fact that I wrote stories, reminded me how amazing it was, to do the work of words.

*

Not that I wrote at all my first year. There was too much to do and experience. There wasn’t enough time. It was a common saying that you could only get two of three: school, social, or sleep. Most everyone accepted a health nosedive as we drank, ate pizza, and came to class bloodshot but still mostly hype. I wasn’t quite so hardcore. I went to parties “to show my face,” but was mostly home by midnight.

I didn’t have a story alive in me then, anyway. Any hope I had of finishing a novel before my program started had vanished that summer, despite several painful, mincing attempts. I didn’t know how to write anything longer than a short story. I didn’t know how to plot. Tension and pacing were beyond me. I read books and articles on those topics, but of course there was no antidote. At some point, I stopped struggling and decided to enjoy my break, then school, instead.

I didn’t really believe the writing could wait. It never feels that way. But it had to.

My desire to write has always come with a hyper-awareness of mortality: I can say no to writing, but what if I die tomorrow? Except self-flagellation wouldn’t help, so, as I’d done many times before, I put writing on the back burner. I felt comforted by its shadow, at least. How I felt the ache of it every time someone told us dream big. If it was lurking enough to trouble me, that meant I hadn’t lost it.

*

Things I learned at HBS that apply to writing:

1. From LEAD (Leadership and Organizational Behavior): There is no such thing as work-life balance, only work-life tradeoffs.

2. From TEM (The Entrepreneurial Manager): If someone around you succeeds, tell yourself: good for them, irrelevant to me.

3. From BGIE (Business, Government, & the International Economy): History is made up of the stories that survive to be told. I’ll never forget how, after a debate about a country’s economics and human rights violations, a classmate from that country said: as a baby my parents fed me the apple and ate the peel. What trust it entailed, to be given that story, to have secondhand access to all these lived experiences I wouldn’t know otherwise. In truth, I came to school prepared to encounter some assholes, which would make for the more amusing essay. But in reality, most everyone was kind and had such startling depths. People were helpful, searingly intelligent—and hot, underscoring the powerful effects of personal maintenance in corporate success. Every day I was grateful to take in this humanity, from these sparkling, vivid, wonderful humans.

4. From STRAT (Strategy): There are no easy answers. Strategy matters, but execution and operations must follow. The perfect strategy means nothing unless you do the rest of it.

*

One of the default assumptions at HBS was the belief that the world was ours for the taking. Not figuratively. Every week our classrooms were graced by the most influential business leaders, well-spoken and polished, bearing such gravity. Bizarrely, these guests would often say, “You guys are so smart. I wish you’d given me advice when I was going through these problems.”

Any hope I had of finishing a novel before my program started had vanished that summer, despite several painful, mincing attempts. I didn’t know how to write anything longer than a short story.Of course we sounded smart. We didn’t have to live with the consequences of our suggestions; we had the benefit of an appendix and the clean narrative of cases. We didn’t know everything, but in that classroom, for the span of time it took you to form a thought and blurt it—it was all right to act like you did. Why not? Everyone else believed too, or had to, to make it through the program.

That belief was unintuitive to me, hope’s perennial adversary. But at the end of my first MBA winter, tired of saying no, I dredged up the will to pull together my short story collection. I identified all the stories I’d want in a book, if I could have one. I sent the manuscript to my editors, who asked if I could write an original story. I said yes and spent the rest of the semester unable to write it.

That summer, in the spaces around my internship, I hacked away at two novellas, because neither was working, and despairingly edited a novelette for the book. I clung to the ethos of at least two words a day, grumpy about every word but persisting.

The second year was better. I took The Moral Leader, a straight-up book club in the MBA curriculum, and two electives that were essentially history courses—War and Peace and The Coming of Managerial Capitalism. I overloaded units to take creative writing workshops at Harvard: immigrant fiction in the fall and advanced poetry in the spring. For three hours, once a week, at the end of a long day debating fundraising strategies and management styles, I sat in an airless room in Barker Hall and workshopped with my classmates, mostly undergrads. My heart went out to the Econ majors straining for corporate internships, trying to keep their storytelling passion alive; and I felt wistful towards the poets, who would likely pursue MFAs, the path I had not taken. Slowly, the hope rose, that little voice saying: You do want this. You do want to give it time. Under the guise of homework, I kept reading, and thinking about stories, and sometimes managed a sentence or stanza that I did not hate.

That winter, I got my contract from Small Beer Press. I sat in Baker Library, scrolling through congratulations on Twitter, trying to collect enough of my brain to finish the case I had started. A passing friend whispered hello, and I found myself grateful for this double life, for the normalcy the MBA gave me, a sudden anchor in the tide of possibility I’d withheld from myself for so long.

That summer, I clung to the ethos of at least two words a day, grumpy about every word but persisting.Then covid struck. One day we were heckling each other in the classroom; the next, everything was shut down, the symphony of our classes reduced to Zoom screens. My section called a hasty gathering, one final chance to be near each other. In our first year classroom, we embraced, and once again I felt the collective heart we’d stitched together, over months of laughing and weeping and “gently pushing back” on each others’ comments.

Despite everything, the semester rolled on. And, in the time I gained by being shut-in all day, I started to write. The stories flared alive again. Through the looming uncertainty of life after graduation, the gauntlet of job interviews and a volatile market, I wrote. We were told to reach for our dreams, but those dreams proved fragile when tied purely to ROI. Words, for the first time ever, were more predictable than my business career. Alumni who had graduated into the 2008 crisis shared their advice: Do what you want, because no one will fault you for this year. Things won’t turn out the way you expect, but you will survive.

I felt that privilege in my bones. How survival, for us, could be a given. HBS did not give me a new dream, but in those hallways I finally felt I could hold that hope without burning. Maybe my debut collection would have happened regardless. But there’s a chance it took this massive safety net to give myself that permission, to remove the mental block that said don’t go for it.

My parents recently asked, gently curious: “When did you write these stories?”

I said the oldest story was written in 2011, and the latest during quarantine. But the simpler answer is: I wrote them when I could. That is really the only time a writer needs.

__________________________________

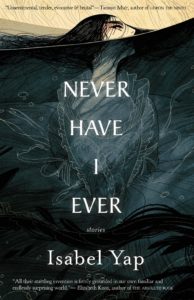

Never Have I Ever: Stories by Isabel Yap is available now via Small Beer Press.