My grandfather was an atomic courier. He drove secret materials for the first uranium-powered atomic bomb from the Manhattan Project city of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to various locations across the country. He liked it well enough to keep driving through the Cold War for the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). My grandmother was a bowling enthusiast and donut-making Cemesto homemaker. My mother and uncle went to high school in a red brick building adorned with a giant atomic symbol containing an acorn as its nucleus.

The atom-acorn assemblage is the totem of the town. Not only is it the ubiquitous symbol of atomic Appalachia, but by linking the community together symbolically it also marks a shared culture and sweeps us up in its substance. For those of us in its orbit, its spinning is our spinning; its hard acorn body, always already full of future potential, is also our collective body, as we embody culture and place. The atom-acorn is a concentration of all the Oak Ridges that have happened, never happened, might happen, and are happening, combined with the ways in which we have made sense of these happenings.

I lived the first few months of my life directly under the atom-acorn totem in Oak Ridge, until my father got a job in a less interesting town in the northeast corner of the state, the finger-shaped part of Tennessee that pokes at Virginia and North Carolina. The place we went to had no secret atomic past and no national laboratory; no atoms with their jaunty capped acorns dotted the landscape. Instead, its claim to fame was a large chicken-processing factory in the center of town.

During the first week after the move, my mother was driving my five-year-old brother around our new town. Zooming down the road cater corner to the chicken factory on a sweltering July day, my mother pulled behind a truck filled with birds headed to their beheading. She had the windows rolled down because the car didn’t have air conditioning. Feathers were flying everywhere. My brother shouted, “It’s snowing!” My mother cried for her loss, for her disappearance from atomic cosmopolitanism, and for her relocation to Morristown, and the regular, less atomic American landscape.

When I was young, I too felt disappointed, robbed of growing up in the science city for smart people, where the nuclear bourgeoisie rubbed shoulders with the future physicists of America, and where the Manhattan Project and the nuclear industries that followed created a new sensorium of everyday and extraordinary experiences. The connection between Oak Ridge and Hiroshima was the first big shock of my life. The facts are stark. Oak Ridge was a secret city engineered by the United States government for the sole purpose of creating fissionable materials for an atomic bomb. The site was chosen for its proximity to the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) dam in Norris, Tennessee, and its steady supply of electricity, as well as for its seclusion.

During World War II, in this secret location tucked between two ridges, over 75,000 people lived and labored for the war effort. Only a small fraction of workers knew what they were producing; the rest knew simply that they were working to support the Allied cause in the war. On August 6th, 1945, most Oak Ridgers learned the true nature of their work from the radio, just like everyone else listening over the airwaves in other parts of the nation and across the world.

The atomic sensorium is not contained in sites: it radiates throughout the city, goes underground, swims and dives through rivers and tributaries. . .

Oak Ridge has been a major nuclear science and security site since its beginning: first as an important node in the Manhattan Project, later as a key production location for the nation’s Cold War arsenal, and now as a place not only for the production and maintenance of parts of nuclear weapons but also as a center for medical research, nuclear storage, national security, and the emergent nuclear heritage tourism industry. The Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and the Y-12 National Security Complex are still the major institutions of the city. These places are important, but the atomic sensorium is not contained in sites: it radiates throughout the city, goes underground, swims and dives through rivers and tributaries, and ignores boundaries and barriers of every stripe. I carry it in my own body. It is both outside and inside, material and immaterial, pulsing and still.

*

In The Nervous System, Mick Taussig likens the shape of the forebrain, which is thought to contain “civilized consciousness,” to a “mushroom-shaped cloud” that hangs over the midbrain, the site of memory. That thought hangs over the words to follow, and as Donna Haraway reminds us, “it matters what thoughts think thoughts.”

*

Cormac McCarthy writes in The Road: “Each memory recalled must do some violence to its origins. As in a party game. Say the word and pass it on. So be sparing. What you alter in the remembering has yet a reality, known or not.” McCarthy and I went to the same high school, 20 miles away from the Atomic City; I trust him and have attempted to heed his advice.

*

A soft poetics of atomic summer rises from the bomb-shaped city. Oak Ridge was my Combray. I visited my grandparents in all seasons, but my atomic childhood features summer. This was when I could go and stay for a week because school was out; when I could swim in the gigantic swimming pool built by the Army Corps of Engineers for the atomic workers and their families, at first just for the white ones and then for everyone. For a while, it was the largest pool in the South. Every hot day and early evening it swallowed me, along with scores of other children I did not know and the occasional lap-swimming adult who sometimes knew my mother. It was in summer that I would run around the track while my grandmother walked, marking each lap with a stone, a remembrance for each ellipse. It was in summer that I would careen down the street on the bright-red skate-wheeled wagon that my grandfather made for me. These activities added up to a giddy triathlon that I was unaware I was training for.

*

For a long time I went to bed early in a lumpy twin bed in a bedroom of my grandparents’ Cemesto “B” house. The little house sat on a street next to other little houses of similar design. They were part of a master plan, housing for the Manhattan Project. The houses were laid out at slightly different angles, as if you were a relatively neat person but happened to be playing Monopoly on a bumpy rug or shag carpeting. In this case, the uneven flooring was the contours of the East Tennessee landscape, the ridges and the rolling hills. The point of this Monopoly game was not a quest for riches and real estate but rather for an atomic bomb.

The “B” denotes the house’s place in the alphabetized scheme. The letters correspond to the size of the house and the number of bedrooms, “A” being the smallest and “E” the largest. The house was built from a material portmanteau—Cemesto—a composite building material made from cement and asbestos with a core of sugar-cane fiber insulation, a filling the texture of cotton candy. Cemesto panels were placed horizontally into wooden frames of the house in order to create the walls. It was introduced in 1937 by the Celotex Company Corporation; a prototype appeared at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City. During World War II, the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill used the Cemesto design to make my grandparents’ home and nearly 3,000 others just like it. After the war and in the spirit of modernism, Cemesto became a favored material for architects interested in low-cost building materials. Frank Lloyd Wright and Charles and Ray Eames were among its newly won fans.

*

My atomic childhood is a Mondrian painting. On the ordered streets and in the uniform houses of the former secret city my grandfather’s blue pickup truck fills a square, his blue jeans color in another, my grandmother’s favorite outfits in red or yellow are folded neatly into others. Their yellow house has its own square, too.

*

Inside those squares could be found yet another square—the Magnavox square. Sometimes my grandfather and I would watch TV together while eating Planters Dry Roasted Peanuts out of their tall jar. He called them goobers. We would consume great big handfuls of them, causing our fingers to become dusty and salty. I thought they were a fancy snack because of Mr. Peanut’s attire and monocle, a snack-sized yellow-legume cartoon version of Proust’s Charles Swann. Our TV watching was much less aristocratic: Hee-Haw was among our favorite shows. Sometimes before our country variety program we would watch the news. This was a good time, unless Ronald Reagan punctured the small faux-wood-paneled square. If the president showed up, I knew our fun would be interrupted. My grandfather, a yellow dog Democrat, would become disgusted and say, “Hell, I can’t even relax for one evening without seeing that idiot get on or off a plane waving like a monkey in a zoo.” At these moments I felt relieved to have been born under Jimmy Carter, the peanut farmer president.

*

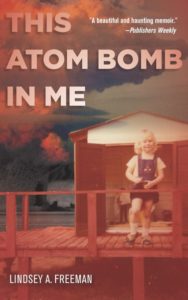

The women who passed by on the sidewalks of Oak Ridge were different from those I knew in Morristown, because they were Mondrians. Cars and trucks tucked into driveways, next to square houses, were also Mondrians. My playhouse made up of only horizontals and verticals, propped up on red-stained wooden planks, was also a Mondrian. I mondrianated in front of it wearing a boxy denim jumper with red buttons, a yellow t-shirt, and blonde hair. The atomic factories on the other side of town were Mondrians, too; they complemented his later, more chaotic period of painting, the paintings he made in the early 1940s as an exile in New York City, the paintings that made up his own Manhattan Project.

*

My mother, too, is a Mondrian—neat and severe in her Oak Rigidness. Her thin black slacks like De Stijl lines, her blonde hair filling a frame, a blue Oxford-cloth shirt tucked into another frame, and still another with her famous yellow pantsuit painted bright and square.

*

In Samuel Beckett’s essay on Proust he writes, “The individual is the seat of a constant process of decantation, decantation from the vessel containing the fluid of future time, sluggish, pale and monochrome, to the vessel containing the fluid of past time, agitated and multicolored by the phenomena of its hours.” As Beckett notes, the past when viewed through the glass of nostalgia is rarely washed in dull tones; it is most often chromatically rich. The images of my atomic childhood in Oak Ridge are vividly rendered in primary colors, which are occasionally taken over by the glowing green that seems to always represent radioactivity. By contrast, my memories of Morristown surface in more muted hues: the cream color of dogwood blooms, the warm brownish rouge of red-clay bricks, and blues mixed with grays, like the shutters that cling to the homes of Colonial Williamsburg.

*

Once while visiting my grandparents, I became sick with a cold: a betrayal of the body in summertime. In winter this seems a logical physical condition, but in summer it feels like a twisted knot in the organization of the universe, throwing off the right order of things. Just as Marcel’s grandmother gave him beer, champagne, or brandy for his asthma in In Search of Lost Time, my own grandmother, attempting to adjust the equilibrium of my small body, gave me children’s Tylenol and put me to bed. Marcel and I both longed to play; for him it was in the Champs-Élysées, while for me it was the Elysian Fields of my grandparent’s honeysuckle-lined backyard. Homer thought Elysium lay on the western edge of the earth by the stream of Ōkeanos; I knew it was in atomic Appalachia, not too far from the Tennessee River.

The images of my atomic childhood in Oak Ridge are vividly rendered in primary colors. . .

When my grandmother left the room, she absentmindedly left the bottle of orange-flavored chewable Tylenol on the nightstand. When I woke I felt much better, leading me to the obvious deduction: if a little bit of medicine made me feel a little better, surely the entire bottle would cure me immediately, basically lacing up my Nikes for me and sending me out to play.

This is not what happened.

*

When I was well, which was almost always, my brother and I would play a Cold War game we called “Mooning the Russians.” It was vaguely related to the space race and the arms race but mostly had to do with showing the Reds our asses. The Ruskies, most certainly spies, would pass by my grandparents’ house trying to seem nonchalant. Wearing t-shirts and driving American-made cars, just who did they think they were fooling? We would show them we knew what was up by dropping our Jams® in their direction. My older brother would order me and I would lower my shorts. We always said “for America!” Once, a carload of teenage Reds really seemed to enjoy the mooning. They orbited the yellow house in their cherry-red hotrod like a planet orbiting its sun, in predictable circles, anticipated trajectories. It wasn’t until the third or fourth time that I realized they were the same spies, only on loop, so crafty were they in their espionage.

__________________________________

From This Atom Bomb In Me. Used with the permission of the publisher, Redwood Press. Copyright © 2019 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. Featured image, “Standard Souvenirs & Novelties, Inc.” courtesy of Digital Commonwealth.

Lindsey A. Freeman

Lindsey A. Freeman is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Simon Fraser University and the author of Longing for the Bomb: Oak Ridge and Atomic Nostalgia.