Meet the Finalists for Next Week's National Book Awards

Interviews with Some of Our Finest Living Writers

POETRY

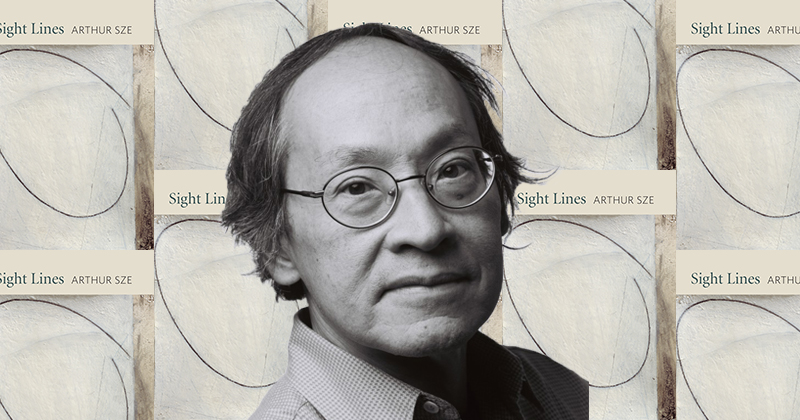

Arthur Sze, author of Sight Lines (Copper Canyon Press)

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

My wife, Carol Moldaw.

What time of day do you write?

I like to write early in the morning when it is still dark. As the sun rises, I see forms emerge out of the darkness. And as daylight brightens, I try to catch that physical wave in my writing.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I turn to translation. Writing out the characters of an ancient Chinese poem and then translating it into English is a way of working with language that can ease the difficulty of figuring out what to write next.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

Two books I return to again and again are Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu, translated by Burton Watson.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

When I was an undergraduate at the University of California at Berkeley, I audited a month-long fiction writing class taught by Lillian Hellman. One day, in her office, she said to me, “I don’t know anything about poetry, but I advise you to write and never stop writing; if you stop writing for even three months, you will lose all the momentum with language you are developing.”

*

Toi Derricotte, author of “I”: New and Selected Poems (University of Pittsburgh Press)

What’s the best book you read this year?

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom by David W. Blight

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

The spiritual nature of writing poetry.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

William Carlos Williams, all books; Rilke, Duino Elegies.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

All of Billie Holiday, especially “Deep Song.”

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

“Speak the unspeakable.” Galway Kinnell.

*

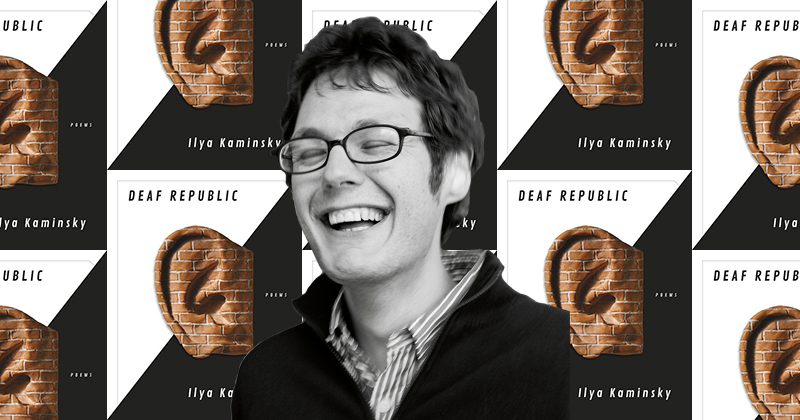

Ilya Kaminsky, author of Deaf Republic (Graywolf Press)

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

My wife, naturally.

My cat was the close second.

What time of day do you write?

I have long ago sold my soul to the gods of night-writing. There is a strange freedom in the night hours, when the images of the day go neatly to sleep in each other’s laps, when you stand alone, naked, before the page, and the night is your only defense & comfort.

Night is especially helpful when one is working on a book long sequence.

That solace-isolation of the night when it is just you, you alone, you very alone: and the world of your book.

As for day time: it is the realm of notebooks, the realm of random lines.

So as the day begins: the lines find their way on paper whether I overhear two boys insulting each other at the gas station, or see a gull cleaning her feet, or two old men playing dominoes on a hood of a car, or two young women kissing at the fish market. They become lines on receipts, on my hands, on a water bottle, on other people’s poems. Lines collect for years, but once in a while they discover that other lines are sexy and, well, the poems may come from that sort of a relationship. If I am lucky. Which isn’t often. But one has to have faith.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

There are so many other things in life! I translate, edit anthologies, wash the dishes, entertain my cat, and try not to disappoint my wife. Or, I write letters to friends about their poems. My friends are so prolific! There is always a manuscript to read and give comments on and play ping pong with. And, it is such a wonderful thing—to be reading your friends’ book-drafts, to be in conversation, to polka inside their heads, mind to mind. What a privilege.

And then, of course, when poems go on vacation, why not pay a visit to an essay?

After all, an essay is a kind of place that loves a lonely visitor with a hat in hand.

Which books do you return to again and again?

In no particular order, the dead writers that come to mind this morning: Shakespeare’s Lear, Pushkin’s Evgenii Onegin, Dickinson. Brooks. Ovid’s Metamorphosis. Akhmatova. Hayden. Mandelstam. Clifton. Issa. Paley. Celan. Cesaire. Edmond Jabes. Morrison. Ritsos. Gilgamesh. Christopher Smart. Pasternak. Anna Kamienska. Wang Wei. Hopkins. Zbegnew Herbert. Tsvetaeva. Weil. Vallejo.

Ah, and, also, for me: Gogol & the hordes of East European fabulists. Why? I realized early on that by temperament, I am not a documentary poet; I am a fabulist.

And, yet, the world pushes through, the reality is everywhere in this fable.

My job is to make this border between the shelter of fable and the bombardment of reality a lyric moment, I feel.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Ha! Is there time? I am afraid that as an immigrant I am always one foot in another literary culture altogether.

See, I wrote verses in Russian for quite some time before we came to America. When we came to this country, I was sixteen years old. We settled in Rochester, New York. The question of English being my “preferred language for literature” would have been quite ironic back then, since none of us spoke English—I myself hardly knew the alphabet. But arriving in Rochester was rather a lucky event—that place was a magical gift, it was like arriving to a writing colony, a Yaddo of sorts. There was nothing to do except for writing poetry! Why English then—why not Russian? My father died in 1994, a year after our arrival to America. I understood right away that it would be impossible for me to write about his death in the Russian language, as one author says of his deceased father somewhere, “Ah, don’t become mere lines of beautiful poetry!” I choose English because no one in my family or friends knew it—no one I spoke to could read what I wrote. I myself did not know the language. It was a parallel reality, an insanely beautiful freedom. It still is.

Is it an escape into another medium?

Well, there is a beauty in falling in love with a language—the strangeness of its sounds, the awe of watching the sea-surf of a new syntax beating again and again the cement of your unknowing. Learning to speak again can be erotic—the unfamiliar turn of the tongue, the angle of the mouth, the movement of lips.

On the other hand, you are so powerless, so humbled, so lost, bewildered, surrounded by nothing but your own confusion. That, too. You don’t know the word, what to do?

And then: the miracle of metaphor. You know other words, they come to redefine what you wanted to say in the first place, you see the world slightly differently from where you began, your mouth makes sounds you didn’t know were possible.

What changes? Even the shape of my face changed when I began to write in English language.

As for non-language things, there are wonder-plenty: Ice skating! Cooking! Dancing at gas stations!

*

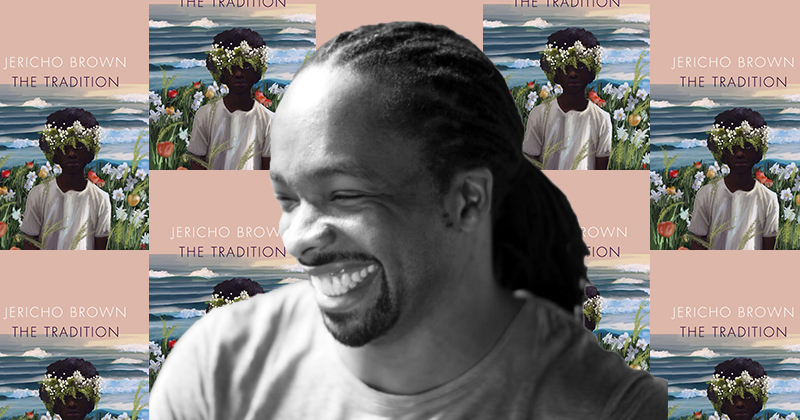

Jericho Brown, author of The Tradition (Copper Canyon Press)

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

I really just want to say that—though it’s one of our biggest fears—writing is not a narcissistic act because what we do is work in the production of beauty. Our relationship to trees is a relation to beauty. If we don’t think people who plant trees are narcissists, we can’t think people who make poems are narcissist. On the contrary, poets are the people who help to make this world livable in the same way that trees have something to do with the fact that we breathe.

What time of day do you write?

I probably do my best work very late at night when it is dark and the world has gone to sleep and there’s no chance of being distracted.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I don’t know what this is. I’m a poet by identity. This means I’m writing all the time. Writing is the way I think. It is not just typing. Most of the writing happens in the mind. I’m not a poet because I have poems; if anything, I feel a little less alive once a poem is done as I don’t know that another will be on the way. I’m not a poet because I’ve written poems. I’m a poet because I write poems, and I’m writing them even as I write the answer to this question.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

I wouldn’t have been able to finish The Tradition if I hadn’t seen Moonlight. I really changed how I could better see myself. I say more about it here.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

“Never say no.” –Nikki Giovanni

*

Carmen Giménez Smith, author of Be Recorder (Graywolf Press)

Who do you most wish would read this book?

I’d be thrilled if the long poem in this book was projected through megaphones in front of the White House.

What’s the best book you read this year?

Ordinary Beast by Nicole Sealey.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

At some point I’d like to talk about the long influence that the music I love and have listened to over the years has had with my poetry, sometimes in very surprising ways.

What time of day do you write?

I write very late at night because the dark keeps me from distraction, which is a big pitfall to me. Distraction could be anything from a picture askew on the wall to a pile of laundry.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I have a set of exercises that I do to generate work like copying a syntax from another poem or reversing the words of another poem, but I also don’t try to hunker down with a single piece of writing, so if I lose steam with one poem, I move on to another one.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.