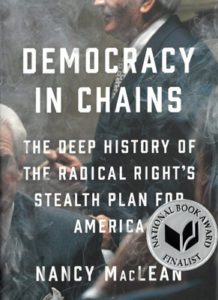

Meet National Book Award Finalist Nancy MacLean

The author of Democracy in Chains on what we need to do now

The 2017 National Book Awards (also known as the Oscars of the literary world), will be held on November 15th in New York City. In preparation for the ceremony, and to celebrate all of the wonderful books and authors nominated for the awards this year, Literary Hub will be sharing short interviews with each of the finalists in all four categories: Young People’s Literature, Poetry, Nonfiction, and Fiction.

Nancy MacLean’s Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right’s Stealth Plan for America (Viking / Penguin Random House) is a finalist for the 2017 National Book Award in Nonfiction. The book is an in-depth study of the radical right, from its beginnings in the mind of political economist James McGill Buchanan to its current form in America. Literary Hub asked Nancy a few questions about her book, her life as a writer, and how to combat the stealth plan of the libertarian right.

Who do you most wish would read your book? (your boss, your childhood bully, Michelle Obama, etc.)

I’m going to answer that question slightly differently. My wish is that somewhere within the radical right there would be someone who can resist the kneejerk impulse to attack me and instead view this book—and urge others within the movement to view this book—as an opportunity to see their movement through the eyes of someone who came to study it with no preconceived notions, someone who used the same academic standards that she used for all her other highly-praised works of scholarship, and who came away from studying a seminal figure within this movement with a determination to expose his ideas and the movement they spawned to the disinfecting light of day. I sincerely wish for them what I would wish for any group that I belonged to. That no matter how painful the process, seeing yourself as others see you is a necessary and helpful process. And yes, for those of you who recognize the phrase “to see ourselves as others see us,” it comes from the Robert Burns poem “Ode to a Louse.” I’ll skip the story within the poem and go right to the three lines that matter here:

“Oh, would some Power give us the gift

To see ourselves as others see us!

It would from many a blunder free us.”

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

I wish we would talk more about the emotions involved in nonfiction writing. People may imagine that scholarly writing is just about assembling the facts and then driving home the point. It isn’t. Not in the research process and not at the writing stage. Because in the end we are not writing about events or ideas but about the people who drove the events or came up with the ideas. And that means we are talking about all the human emotions—from greed to fear, from desire to disgust, from pride to vengeance. Understanding the human beings behind the story is as intrinsic to scholarly history as it is to fiction.

Who was the first person you told about making this list?

The first person I told was my husband, because he is my strongest supporter. He has lived with the emotional and intellectual roller coaster of this book for eleven years now, and his advice has always been on the mark. For example, he urged me from the very beginning to inhabit my subjects’ points of view as fully as possible, difficult though it would be, because my contribution should to be enable readers to understand this worldview on its own terms, in context, from the inside out, so they can appreciate the appeal of what might otherwise seem foreign and inexplicable to them.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I confess that I don’t often suffer from writer’s block, perhaps because I treat writing like carpentry or another skilled trade, meaning I try not to mystify it. I just practice my craft to get the job done. On the rare occasions when I do feel genuinely blocked, I have learned that it’s almost always because I don’t really know what I mean to say, so the block is a signal to go back to my primary sources and read them more closely or seek out additional sources that would cut through the knot. And then sometimes, if it was a big knot, a nap helps re-boot my brain before I go back to writing.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

Thinking Like Your Editor, by Susan Rabiner, my agent. My copy of the book is underlined, highlighted, dog-eared, and studded with Post-its. After more than thirty years of writing for other scholars, I needed expert coaching to retrain myself to write in a way that could convey complex and urgent ideas to general readers, which requires both good storytelling and no-jargon shortcut prose. Susan’s book helped me through that transition and so I go back to it again and again. I tease her that she was the Anne Sullivan to my Helen Keller: I knew deep down what I wanted to say but it took hard work and coaxing to get it out.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

The one non-literary piece of culture I cannot imagine my life without is film. By engaging so many senses and emotions, it helps me get outside my head like nothing else. A case in point is the 2016 film Moonlight, which a friend aptly described as visual poetry. In one exquisite early scene, the lead character, a tormented young man, learns to swim by trusting a veritable stranger to hold him afloat. The image of him letting go and experiencing the miracle of the ocean for the first time told a truth that words alone never could. It pierced my heart with the redemptive power of simple kindness, and how openness to it can change one’s life.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

The best writing advice I’ve ever received was “one dragon at a time”: that is, focus on the challenge right in front of you and don’t look up at the others assembling in the distance or you will be paralyzed. It’s a version of Anne Lamott’s “bird by bird,” but it better evokes the understandable fears that can impede forward movement and completion.

What could (or should) the left do to respond to the right’s “stealth plan”?

I should start with a caveat: I am a historian, not a strategist, so my main contribution is to explain how we arrived at this moment of profound political crisis. That’s not nothing, of course. As one reader, a public health nurse, put it: you have to get the diagnosis right before you can determine the correct treatment plan.

That said, though, speaking as a historian and a concerned citizen, my advice would be three-fold.

First, we need to get out of our own particular interest silos and into conversation with those who share our values and our concern about where our country is heading. The radical libertarian right I wrote about is seeking to undermine the entire twentieth-century model of government built up by citizen action, from minimum wages and workers’ rights to antidiscrimination laws and environmental protection and more, and to, in effect, steal millions of our votes in the process, by keeping many people away from the polls and misrepresenting the will of others through extreme gerrymandering. That means that getting out of our comfort zones and into conversation with others we have not yet met, yet who are also endangered, will be crucial to prevail. When I talk with audiences about the action implications of my book, I quote Bernice Johnson Reagan, a black feminist who counseled about coalition building, “stretch your perimeter. If you are not feeling the strain, you are not doing the work.”

Second, as we expand our sense of who “we, the people” are, we need to keep in mind that past crises of this magnitude in our history have also proved to be opportunities for national renewal. Democratic forces only triumphed over the enemies of collective self-government by redefining the meaning of citizenship and the purposes of our institutions. We saw that in how radical Reconstruction was needed after the Civil War to truly end slavery and defeat the power-hungry planter class—by enfranchising freedmen and endowing them with legal rights. We saw it again in how the New Deal was needed during the Great Depression to push back the property supremacists who would have left Americans vulnerable to the siren calls of fascism or communism. By enabling working people to build power and all Americans to feel hope for the future, it saved liberal democracy. To quote Naomi Klein, “No is not enough”: people need a vision to say yes to if they are going to make the commitment needed to prevail over plutocracy.

My last piece of advice is don’t panic: don’t do anything stupid (like violence or more of the venomous name-calling that only helps the right).

The single most important finding of Democracy in Chains is this: that the Koch network is doing what it’s doing in the way that it’s doing it because the architects of this plan know, from repeated experience, that if Americans are told the truth about what the libertarian right is ultimately seeking, they will reject it and try to stop it. And so the plan must advance by stealth: by misinformation and falsely packaged radical rule changes. That’s frightening, it’s true. But the right’s fear of a latent majority is also a colossal source of potential strength, all the strength needed to rout the donor-funded demolition team. And that means the single most important thing that needs to be done is to patiently inform and activate the millions of good people who will seek to stop this if they see what is being imposed on them and how.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.