Meet Laddie Boy: The First Celebrity Presidential Pet

On President Warren G. Harding’s Airedale Terrier

“Whether the Creator planned it so,” Warren Harding once wrote in the Marion [Ohio] Daily Star, “or environment and human companionship have made it so, men may learn richly through the love and fidelity of a brave and devoted dog.” The legacy of the twenty-ninth president of the United States—whose administration historians routinely rank with Andrew Johnson’s and James Buchanan’s as one of the worst in American history—is debatable. What cannot be doubted, however, is Harding’s deep affection for dogs.

Harding, who owned the Marion Daily Star prior to winning the presidency, also possessed a keen understanding of publicity, and he kept his Airedale terrier, Laddie Boy, in the public eye. For a nation still reeling from the apocalyptic devastation of the Great War, regular updates on the life of the president’s dog proved irresistible. Laddie Boy became the first celebrity presidential pet.

Warren Harding, a sitting senator from Ohio, won the Republican Party nomination in 1920. It was the first presidential election since the passage of the 19th Amendment, which guaranteed women the right to vote. Harding was charming and handsome, and his party’s support of Prohibition and opposition to President Wilson’s League of Nations helped him cruise to victory with 60 percent of the popular vote.

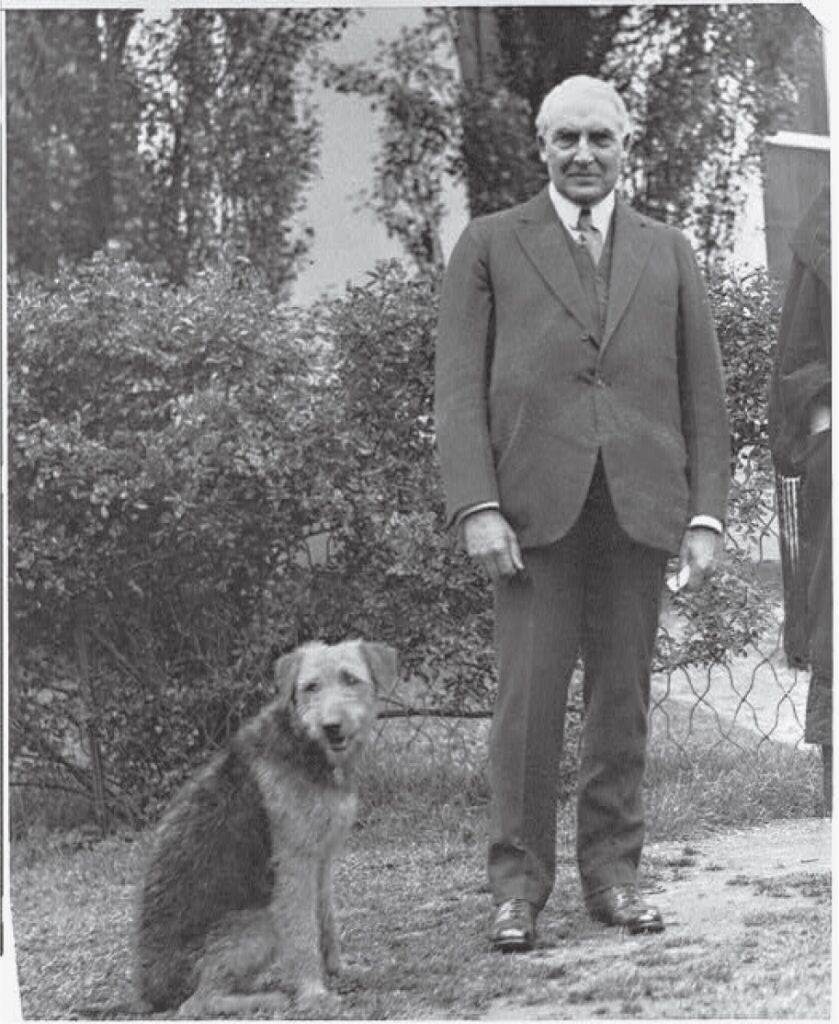

President Warren G. Harding with his Airedale terrier, Laddie Boy. While President Harding is not well regarded by historians, no trace of scandal taints his dog’s legacy.

President Warren G. Harding with his Airedale terrier, Laddie Boy. While President Harding is not well regarded by historians, no trace of scandal taints his dog’s legacy.

Harding and his wife, Florence, did not have a dog when they moved into the White House on March 4, 1921. Laddie Boy, a puppy who was born on July 26, 1920, at Caswell Kennels in Toledo, Ohio, arrived the very next day. The president ordered his staff to bring the dog to him immediately upon arrival, and Laddie Boy’s appearance disrupted Harding’s first cabinet meeting. For the rest of Harding’s time in office, Laddie Boy would attend these meetings, and he had his own chair, like any cabinet secretary.

Airedale terriers are intelligent, having been bred for independent hunting. In the United Kingdom, they were used as military canines during World War I. They are occasionally referred to as the “king of terriers,” as they are the largest dogs of that type. While their intelligence can make them stubborn and somewhat difficult to train, Harding appears to have had few difficulties. The New York Times reported that within a week of his March 5, 1921, arrival at the Executive Mansion, the president’s puppy had learned to fetch the newspaper in the morning, bringing it to his master without incident.

Perhaps Laddie Boy simply wanted to brag about the media coverage he received. Both the Times and the Washington Star ran items about the dog almost daily. The president granted the media unprecedented access to his dog, and he rarely went anywhere without him. Laddie Boy was known to accompany Harding on golf outings, and he joined the First Lady at fundraising events. The dog’s fame was such that Harding had a thousand miniature likenesses of Laddie Boy produced, and he gave them to supporters as souvenirs. These tiny Laddie Boys are now highly prized collector’s items.

On rare occasions when the president felt his dog’s media presence shrinking, he composed letters “from” Laddie Boy to major newspapers. In February of 1922, the New York Times published one such letter: “So many people express a wish to see me, and I shake hands with so many callers at the Executive Mansion,” it read, “that I fear there are some people who will suspect me of political inclinations. From what I see of politics, I am sure I have no such aspirations.”

For Laddie Boy’s first birthday, Caswell Kennels sent him a bone-shaped cake. Accompanying this treat was a letter of encouragement “written” by the First Dog’s father, Champion Tintern Tip Top. The letter expressed pride in Laddie Boy, whose antics were documented regularly in the local Toledo press. The relentless press coverage spurred a public desire to own Airedale terriers, and the breed’s popularity increased dramatically. Toy companies attempted to profit from the dog’s popularity, and several contacted the White House seeking exclusive rights to an “official” Laddie Boy likeness, but the president refused to endorse any particular stuffed animals of his dog. Given the deep-seated corruption of many officials in his administration, this principled stand feels highly ironic.

By the summer of 1923, that corruption was catching up to Harding. His secretary of the interior, Albert Fall, had leased government lands to oil companies in exchange for personal loans. The press began to pursue the scandal—known as the Teapot Dome—as they had once pursued stories of the Hardings’ dog. In an effort to distance himself from these ongoing troubles, President Harding traveled to the western United States and up to Alaska, then a U.S. territory. (He was the first president to visit Alaska, and he was photographed with a team of sled dogs while there.) During a stay in San Francisco, the president, who had not been feeling well for some time, died on August 2, 1923. The general public, who had been told days earlier that Harding had suffered gastrointestinal issues but was feeling better, was deeply shocked by his sudden death. The First Lady did not consent to an autopsy, but modern scholars believe he died from cardiac arrest. The nation, not yet fully aware of the corruption of Harding’s administration, mourned deeply.

Laddie Boy had not joined his owners on their western excursion, and his handlers at the White House noted sadly that the dog awaited their return. The Associated Press reported:

There was one member of the White House household today who could not quite comprehend the air of sadness which hung over the Executive Mansion. It was Laddie Boy, President Harding’s Airedale friend and companion. Of late he has been casting an expectant eye and cocking a watchful ear at the motor cars which roll up on the White House drive. For, in his dog sense way, he seems to reason that an automobile took [the Hardings] away, so an automobile must bring them back. White House attachés shook their heads and wondered how they were going to make Laddie Boy understand.

A poet named Edna Bell Seward composed a poem called “Laddie Boy, He’s Gone.” (“Not alone, your dog’s heart breaking for a glimpse of him again.”) The poem was set to music by George M. Seward and was published as sheet music so grieving Americans could gather in their parlors and sing condolences to the bereaved dog.

Imagine a nation grieving the death of a president, gathering around their pianos to sing mournful songs to the president’s dog.

Imagine a nation grieving the death of a president, gathering around their pianos to sing mournful songs to the president’s dog.

The nation’s newsboys, in recognition of the deceased president’s former occupation, collected pennies for a unique tribute to Harding. Nineteen thousand were collected and converted into a statue of Laddie Boy. (The dog, ever a good boy, sat for the sculptor, Bashka Paeff, on fifteen separate occasions.) The finished statue belongs to the Smithsonian but is not currently on display. After her husband’s death, Florence Harding gave Laddie Boy to Secret Service agent Harry L. Barker, whom she viewed as a son. Barker transferred to Boston when his White House service ended, and he took the iconic Airedale with him. Laddie Boy lived with the Barkers until 1929, when he passed away, reportedly of old age. The media darling once again made the papers. The Times reported that the dog passed with “his head on the arms of Mrs. Barker.” The family buried him in Newtonville, Massachusetts.

Laddie Boy’s legacy extends far beyond the decade in which he lived. His role as media darling set the stage for the much-loved presidential dogs to come—from Franklin Roosevelt’s Fala to Barack Obama’s Bo. The media attention Laddie Boy generated, cannily encouraged by President Harding, helped create the standard for presidential dogs, and it planted the idea of White House pets firmly in the popular imagination. Every subsequent animal to roam the living quarters of the Executive Mansion does so in the shadow of Laddie Boy. He remains President Harding’s lasting contribution to American life.

______________________________________

From All American Dogs: A History of Presidential Pets from Every Era © 2022 by Andrew Hager. Reprinted by permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Andrew Hager

Andrew Hager serves as historian-in-residence for the Presidential Pet Museum, a position he has held since 2017. Prior to that, he taught middle school social studies and language arts for a decade. Andrew is legally blind and travels with a black Labrador retriever named Sammy. He lives with his wife, Kristy, and their two children, Mia and Ian, in the suburbs outside of Baltimore, Maryland. In addition to Sammy, the family has a fluffy mixed-breed rescue named Emmy and two cats, Sophia and Olivia.