Meet Britain's First Woman Soccer Player, Nettie J. Honeyball

The Founding of the British Ladies Football Club Was Met

with Violent Resistance

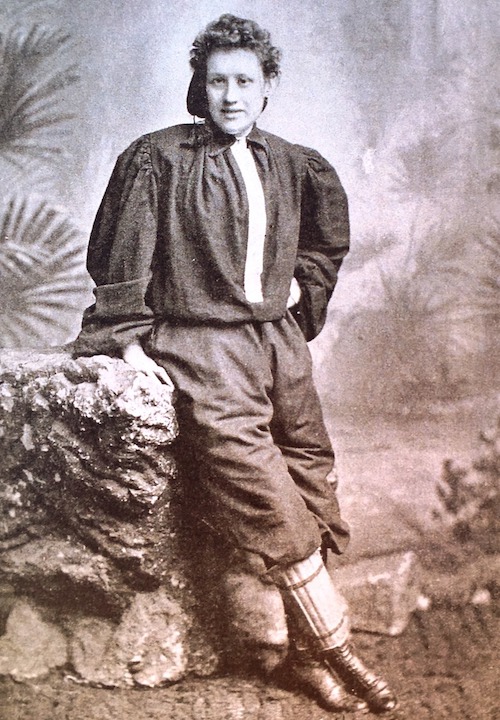

The young woman in the photograph has pale skin, dark eyes, and a mass of strawberry-blonde curls piled on top of her head. Her hand rests on her hip; her chin is slightly raised. She stares at the camera with a look of defiance, energy, and excitement, although there is, perhaps, a faint trace of trepidation behind her smile.

Her photograph appeared in the Daily Sketch, a British tabloid newspaper, on February 6, 1895, alongside an interview with “Miss Nettie J. Honeyball,” one of the world’s first “feminine footballers.”

When she spoke of her decision to form the first British Ladies Football Club, her words appeared in shocking contrast to the deeply traditional, chauvinistic mores of Victorian-era Britain. She said, “There is nothing farcical about the British Ladies Football Club. I founded the association late last year, with the fixed resolve of proving to the world that women are not the ‘ornamental and useless’ creatures men have pictured. I must confess my convictions on all matters, where the sexes are so widely divided, are all on the side of emancipation, and I look forward to a time when ladies may sit in Parliament and have a voice in the direction of affairs, especially those which concern them the most.”

But to her audience, the most audacious part of the article wasn’t what she was saying but what she was wearing.

In 1895, Victorian Britain was a land of extremes.

Men were seen as superior in every sense—intellectually, physically, emotionally. Women were confined to domesticity, to an entirely separate sphere from their husbands, brothers, and sons, who went out to work. Increasingly, middle-class girls were encouraged to study within the home—music, singing, languages—but their skills were only being honed with a view to making them more marriageable. They were to learn nothing too intellectual, lest they intimidate a potential spouse.

And their clothing was prohibitive, cumbersome, and dangerous to wear. Women were expected to wear crinoline underskirts with steel hoops, cloth skirts that kept their legs covered down to the ankle, and corsets that squeezed their stomachs and chests. Everything, for Victorian women, was a bind. But the combination of domestic confinement and increased study gave middle-class women the impetus to take steps toward emancipation, to begin campaigning for the right to vote and the right to wear “rational dress.” For Nettie and her cohorts, rational dress was a huge part of forming the British Ladies Football Club. In the picture that had so scandalized Daily Sketch readers, Nettie had been wearing a men’s uniform: a long-sleeved shirt, shorts, long socks, and shin guards. Nobody had seen anything like it before.

As she wrote in a letter to another newspaper, “There is no reason why football should not be played by women, and played well, too, provided they dress rationally and relegate to limbo the straight-jacket attire in which fashion delights to clothe them.”

The hostility of the crowd and the press coverage served to prove her point that society still viewed women as ornamental, incapable of athletic prowess.

Yet while women like Nettie were fiercely advocating for great changes, ancient attitudes prevailed. The same year that the British Ladies Football Club formed, a woman named Bridget Cleary was murdered in Ireland, burned alive by her husband and several neighbors who suspected she had been replaced by a witch. The trial gained a great deal of attention in the press, serving as a stark reminder that a woman with a modicum of free will was to be feared and subjugated.

As Nettie was about to learn, the more moves women made to broach equality, the more they met with hatred and hostility.

In the early part of the year, advertisements began appearing in the English newspapers:

The British Ladies Football Club. Ladies’ Football Match, North v. South, will be played on the Maidenhead Football Ground on Easter Monday Afternoon. Kick-Off at 3.30 pm. Admission 6d. Enclosure & Pavilion 1s. extra.

Ladies desirous of joining the above Club should apply to Miss Nellie J. Honeyball, “Ellesmere”, 27, Weston Park, Crouch End, N.

The notices promised an esteemed guest at the match as well: Lady Florence Dixie, a well-known novelist, newspaper columnist, women’s rights advocate, and member of the aristocracy. Dixie and her family were no strangers to newspaper coverage. Her father, the Marquess of Queensberry, had accused Oscar Wilde of an illegal homosexual affair with his son and was fighting slander charges in court. Dixie herself had been so forthright in her advocacy of women’s suffrage that she had received a letter bomb in the mail and had allegedly been attacked and stabbed by two men dressed as women while she was out walking her dog. Dixie had been approached by Nettie to act as a spokesperson for the upcoming game, the first of many for the BLFC, Nettie hoped.

The publicity worked. The match attracted around ten thousand spectators, who poured through the single turnstile at the revised venue of Crouch End in north London before kickoff, bringing to the lush field an atmosphere of curiosity and disdain.

A little before four in the afternoon, the Ladies ran onto the field, divided into the two teams, North versus South London. In James Lee’s comprehensive account, from The Lady Footballers: Struggling to Play in Victorian Britain, the sound that rang out around the ground was a mix of cheers and jeers. Some men fell about, laughing, at seeing the women running in shorts; others yelled out derisive comments. It made the women, who had only been playing for a few weeks, nervous, and the first three goals scored were own goals. Many of the spectators decided they had seen enough and filed out, pouring scorn on the women’s abilities. The most talented player on the field, Miss Gilbert, who powered her North side to a 7–1 victory, was deemed to be a man in disguise and was subjected to shouts of “Tommy!”

Newspaper coverage widely labeled the women’s efforts a “farce” and a “joke” and commonly resorted to attacks on the women’s physical appearance. Their dress was unbecoming, and worse, apparently, for the male journalists reporting on the game, the women were not what the men would describe as “beauties.”

It was only the beginning for Nettie. The hostility of the crowd and the press coverage served to prove her point that society still viewed women as ornamental, incapable of athletic prowess.

With the club up and running, Nettie took her teams on a tour of England in the months that followed. They played at a range of playing fields and stadiums belonging to long-established men’s teams; some of local press coverage was supportive and encouraged the crowds to cheer, while some remained cynical and derogatory.

An article in the Newcastle Daily Journal read, “With the advent of the new woman, it was only natural that she should have a desire to compete in those games which have been looked upon as being exclusively the property of man.” Meanwhile, an editorial in the Blackburn Times gave the opposing view: “Woman in her place is a charming creature [but] the idea of donning foot- ball shirts, knickers, and shin-guards, and trying to ape the man is somewhat disturbing to one’s peace of mind. . . . Let them look to their hop-scotch and skipping-ropes, and leave cricket and football to the boys.”

The latter view began to permeate audiences, and by the end of the tour, crowds had petered out into the hundreds. Mrs. Graham, one of the club’s most talented players, who played both in goal and as an outfield player, refused to give in. She organized a tour of Scotland the following year, during which Mrs. Graham’s XI would take on some of Scotland’s men’s teams. It was a bold idea—one that ended in carnage.

If the majority of men were apathetic about seeing two teams of women playing a soccer match, seeing them play against their own gender sparked a violent reaction. During their first match at Irvine, one of the male players smashed into one of the women, giving her a black eye. The incident served as a portent of something dark and sinister brewing. The women called a halt to the game, and it was reported that the crowd had invaded the field and surrounded the women, forcing them to kick and push their way back to the clubhouse.

Nine days later, an angry mob attacked Mrs. Graham’s XI after a match in Glasgow. The women were about to be taken to their hotel in horse-drawn cabs when several thousand rioters descended on their convoy, smashing windows and attacking the drivers and players, even injuring a police officer. Mrs. Graham was wounded as she tried to protect her players, her arm badly sliced up by flying glass.

Despite the occasional positive reception, the women never knew quite what to expect when they arrived for a game. As violent incidents escalated, it became clear to all that it was no longer safe for the women to play. The English FA compounded things further by banning their men’s teams from playing against women. The first attempt to popularize women’s soccer, a daring and death-defying effort, had come to an upsetting conclusion.

__________________________________

This article has been excerpted from Soccerwomen: The Icons, Rebels, Stars, and Trailblazers Who Transformed the Beautiful Game by Gemma Clarke. Copyright © 2019. Available from Bold Type Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Gemma Clarke

Gemma Clarke is a British sports journalist based in the US. She has written about soccer for The Guardian, The Observer, The Times (UK), The Daily Telegraph, and the London Evening Standard. She was writer and editor of the League Leader and the first female publications editor for a Premier League soccer club. She wrote minute-by-minute reports on the FIFA Men’s World Cup for The Guardian online, as well as reporting on the Women’s European Championships and the Men’s Blind World Cup. She worked as a production assistant at Sky Sports News and as a stringer for the sports news agency Hayters Teamwork.