Maurice Carlos Ruffin on Understanding Voice in Fiction

"I write as a conductor, not as a performer."

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

One of the most mysterious elements of craft is voice, or how a work of fiction comes to sound like itself.

I’m a terrible singer. Before I was self-conscious, I sang all the time as a child. During those years, my confidence increased, if not my talent. There was a brief period in my twenties when I could hold a note and match, say, Tevin Campbell or Mary J. Blige, but sadly, I didn’t press my advantage. I let go of the modest gains I’d made. I stopped singing. Today, even my shower is safe.

Still, despite my limitations, I’ve always had a good ear. As a child, I also played violin and later string bass in a youth orchestra. Look, I wasn’t a great string player either. But I was an excellent listener. And although I felt like a stowaway among so many talented young musicians, my imposter syndrome didn’t prevent me from enjoying the experience. Bass players got more downtime, on average, than the rest of the performers. This meant that I could take a measure or two to luxuriate in the diverse sounds around me: the swooning violins, the syrupy cellos, the epic trumpets, the angelic choir. I often daydreamed that I was the conductor. Directing traffic. Controlling time. Preventing chaos.

I write as a conductor, not as a performer. I rarely hear my own voice on the page. Instead, I make space for all the other voices.

As a novice writer, I usually started with a concept. What if this? What if that? Wouldn’t that be interesting? Those early stories often felt stilted because I was trying to sing all the parts and play all the instruments. A one-man band.

Eventually, I matured enough to listen to the voices of my characters, to let them play the instruments. I’ve written over a hundred stories by now. Each narrator has a different timbre, pitch, intensity, and cadence. One of my MFA classmates gave me a concept that I still use. My first-person and second-person narrators are singing. The narrators in my third-person stories are playing their instruments.

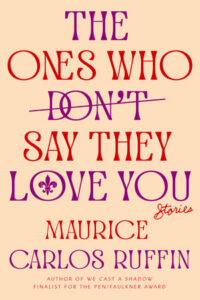

Together, the 20 or so lead characters in my New Orleans-set short story collection, The Ones Who Don’t Say They Love You, make up a large band with chorus. James, the elegant protagonist in “Ghetto University,” sings in a smooth tenor. Shaquann, the irrepressible trans girl in “Rhinoceros,” is the living embodiment of the drumbeat in every bounce song ever made. And Gailya, who is at the heart of the one novelette in the collection, “Before I Let Go,” is gently playing a piano in the dark.

The point of this extended metaphor is that I don’t make the voices. And perhaps neither should you. I listen. Then I wave my hands around to make sure the song stays on beat. I may glare at a character if they seem to lose the plot. But they tell their own stories. And thank goodness for that.

*

Read more on voice in fiction:

Sharon Harrigan on writing from a collective point of view.

Marisa Silver on moving between different characters’ perspectives.

Pamela Erens on developing the voice of a young protagonist.

Jennifer duBois on stealthy first-person narrators.

*

5 Books with Brilliant Voices

RECOMMENDED BY MAURICE CARLOS RUFFIN

Victor Pelevin, tr. Andrew Bromfield, The Sacred Book of the Werewolf

Toni Morrison, A Mercy

Nafissa Thompson-Spires, Heads of the Colored People: Stories

Celeste Ng, Little Fires Everywhere

Lisa Taddeo, Three Women

__________________________________

The Ones Who Don’t Say They Love You by Maurice Carlos Ruffin is available via One World.