Massoud Hayoun on What It Means to Identify as Both Jewish and Arab

Untangling the Imperfect Narratives of Religious History

There are many potential origin stories for the Jewish Arab—a tiny fraction of humanity at the nexus of so much that’s wrong with the world. The recollection of my grandparents’ lives is itself an origin story, but before we embark on that, I’ll convey to you what may have come before them: a perfidy of beginnings, real and imaginary. Some of these stories my grandparents passed to me as a child, in Los Angeles, in their anecdotes and tall tales. Others I learned much later, filling in the gaps.

There are no conclusive origin stories or absolute answers. Not to the Arab identity, or the Jewish one, or the North African one. Not to the mix of the three that I claim here. I hope you take heart in the imperfections of my account. Absolute answers are the first signs of a sinister political project brewing beneath the surface.

My grandparents’ stories began and ended where they found energy to tell them and meaning in their retelling. They had an agenda. Implicit in their stories of goodly women and men in our family was the demand that I not fuck it all up by being undignified. Origin stories often come in the form of bedtime stories. But they serve a political purpose. They give us a mandate to live in solidarity with or in opposition to each other. Like previous origin stories, this book has a political agenda. The main difference is that I’m telling you, upfront: my intention is to reclaim the Jewish Arab identity for me and to recuperate it as a stolen asset of the Arab world.

There are many imagined origin stories offering clues to the antecedents of the Jewish Arab and, more specifically, my grandparents. I’ll lay out a few for you here, in this chapter, but it is important to note that, even with all the legitimate history interspersed with these stories, the consensus in academia is that many of these accounts are totally inaccurate and ultimately useless to a scientific understanding of world civilizations. But that doesn’t mean they’re devoid of meaning. We decide for ourselves what counts.

Many Arabs—my grandparents and non-Jewish Arabs I’ve encountered—speak of the Arab people that exists today as one descended from specific Arabic-speaking tribes in the Arabian Peninsula, mostly polytheists until the Prophet Mohammed introduced Islam.

But if the view of a homogenous Arab nation—one narrowly descended from the Arabian Peninsula without significant intermarriage or evolution from the first Arab arrivals in North Africa—holds, then how does one explain the culturally diverse Christian and Jewish Arabs, the many people of Amazigh and Phoenician descent who identify as Arabs, Iran’s ethnic Arabs? What of Arabs whose ancestors arrived more recently, escaping the Armenian genocide to join preexisting Armenian communities in the Arab world? Reality itself runs counter to the concept of Arabness prevalent among Arabs today. And yet that doesn’t nullify the importance of an abstract belief in the Arabs’ roots in the Arabian Peninsula. If the first Arabs aren’t my blood ancestors, they founded a civilization of which my ancestors since time immemorial became a functioning part.

By the same token, many Jews—who in reality are of all skin colors and ethnicities, Argentine and northern Chinese—speak of themselves as a singular Am Yisrael, a Nation of Israel— as though, despite their apparent Ethiopian-ness, Iraqi-ness, Russian-ness, German-ness, and so on, their ancestors were the ethnically homogenous descendants of that ancient Kingdom of Judah who magically morphed into distinct nationalities. Does the global Jewish faith community possess superhuman powers of phenotypic assimilation? No. And yet, in the practice of Judaism, it is inarguably useful to imagine our faith community’s forebears as a single community that suffered slavery under pharaohs and emerged, delivered by the hand of God, together. In the abstract. In spiritual stories, of immeasurable value but still not firmly rooted in this world.

Amid these origin stories is a murky place where documented history and faith intersect. Implicit in these piecemeal retellings of origins is a perhaps sobering truth: our concepts of self and of history are much less an exact science than we’ve been led to believe. The past is shrouded in imperfect narratives. We can choose, as I do, to both ascribe meaning to and realize the practical limits of origin stories, like the Jewish Arab’s imagined roots in the Arabian Peninsula and in a Biblical Nation of Israel emerging from Egypt. And that’s good. We can still wrench our histories back from the hands of people once exclusively empowered, often by colonial conquest or class dominance, to write them.

Our concepts of self and of history are much less an exact science than we’ve been led to believe. The past is shrouded in imperfect narratives.

Conquest is a running theme of the many origin stories for North Africa, which I use in the most physically broad and inclusive sense to mean the region that stretches atop the continent from Egypt to Mauritania. Before the Common Era, North Africa had already seen conquest by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, and the Romans. The physical landscape of North African cities was likely built and razed several times over before the construction of what became the Roman ruins that dotted the landscape of my grandparents’ hometowns. In the 7th century c.e., the Arab conquest swept the region, bringing with it Islam. In the 16th century, Ottoman wars of conquest wrested control of North Africa from a host of indigenous and European controllers. Finally in the 19th and 20th centuries, the region fell to colonial European, mainly French and British, control.

Of course the question becomes, Why would I choose to identify with one particular element of these conquests? The answer is that Arabness is what ties me to people from Marrakech to Manama who share a similar legacy and, in my experience with them, recall to me things I know of my family and self in the way that they live their lives today. That Arabness does not, to my mind, negate the sacred things that came before, in which I also take great pride, namely my Amazigh-ness and my Judaism. I can feel Arab, first and foremost, without forgoing or denigrating other simultaneous identities.

The Amazigh people (the Berbers) who predated all the successive conquests are themselves a diverse group of people of different dialects, skin tones, and cultural practices. My grandparents never spoke to me of the Amazigh people as a child. We had left our region long before the Amazighist movement of the late 20th century fought for greater recognition of North Africa’s earliest antecedents. It wasn’t until long after my grandfather’s death that I realized that the strange community and the language separate from Arabic to which he referred occasionally when talking about his ancestors was the Amazigh community and the Amazigh language, Tamazight. For my grandparents, in their stories from North Africa, there were more often two classes of humans: there were North Africans and there were the Europeans. The stories they told involved Muslim and Jewish and Arabic-speaking and Tamazight-speaking characters, but all of those were part of a society def ined in contrast to the European invaders. In my later conversations with my grandmother, unless I asked, the religious and ethnic identities of the North African people in her stories were rarely evident.

As an adult, attempting to fill the gaps in the stories they’d told, I was especially captivated by one Amazigh origin story that sits squarely at the intersection of fact and fiction, the story of Queen Dihiya.

In North Africa, before all these carefully measured nations with borders and the paper permits needed to cross them, there was a region from the Atlantic to the eastern Mediterranean called Tamazgha, and the people that lived there were called Amazigh—Imazighen in the plural—Free People. Among them were many different tribes—the Irifyen, the Shleuh, the Iqvayliyen, for example. Many of the communities that existed then endure in some form; many don’t. The Imazighen were a matriarchal society that predated the arrival of monotheism on the continent of Africa. Before the Arabs arrived in Tamazgha, there was a warrior queen who was from what historian Ibn Khaldoun described in the fourteenth century c.e. as the Jewish Amazigh Djeouara tribe. She was named Dihiya—“gazelle” in Tamazight. The Arab invaders called her the Kahena, the priestess. The history, as recounted by Ibn Khaldoun, describes her as a witch with the power to foresee marauding invaders from hundreds of miles away. (This is when the Imazighen began to be known as Berbers: the Arabs called them that because Tamazight sounded to them like a babbling brook, berberberberber, and the name, forged in misconception, stuck.)

In the time of the Ummayad Caliphate, the Islamic empire that reigned over the Arab world and Spain in the 7th and 8th centuries c.e., Dihiya is said to have battled the Arab invaders three times. In the first two battles, the Arab army outnumbered Dihiya’s and their weapons were far more advanced, and still the Ummayad faced great difficulty defeating her. Finally, the Ummayad army sent her head to the caliph, Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, in far-off Damascus, an assurance that North Africa had been won.

Countless questions emerge from this origin story that purports to explain how North Africa became Arab. Does the contemporary North African call the Amazigh our ancestor? Or does the North African call the Arab invader our ancestor? Or was a new people forged from a generation’s violence?

Dihiya’s story—the facts and the creative embellishments that emanate from it—has been used by a host of political actors in North Africa. To the French who conquered the region over the course of the 19th century c.e., she would serve as a symbol of the otherness of the Arab. The Arab too had invaded and conquered, the French would teach, attempting to legitimize their own conquest over an Arab majority they simultaneously classed as indigenes. Imazighen who continue to fight socioeconomic and political marginalization in their countries today often conjure Dihiya as a symbol of their age-old resistance to Arab dominion. North African women’s rights activists of all ethnic and religious identifications have also used her as proof that North Africa is, at its base, a society of women who know how to fight. Often, in the Jewish North African telling of this story, Dihiya underlines that the Jewish North Africans have longer-running roots in North Africa than their Muslim compatriots. And in the same way that the story has been used in French histories of North Africa to establish a world in which people identifying as North African Arabs and Imazighen are eternal adversaries, it pits Jews against Muslims. In teasing out long-forgotten divisions, Dihiya’s story, one that prefigured the French invasion of North Africa by centuries, was manipulated to suit the colonial politic of divide and conquer that guided France’s conquest of our region.

__________________________________________

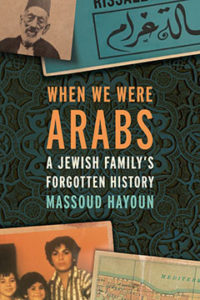

From When We Were Arabs by Massoud Hayoun. Used with permission of The New Press. Copyright © 2019 by Massoud Hayoun.

Massoud Hayoun

Massoud Hayoun is a journalist based in Los Angeles, most recently freelancing for Al Jazeera English and Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown online while writing a weekly column on foreign affairs for Pacific Standard. He previously worked as a reporter for Al Jazeera America, The Atlantic, Agence France-Presse, and the South China Morning Post and has been published widely. He speaks and works in five languages and won a 2015 EPPY Award. The author of When We Were Arabs: A Jewish Family’s Forgotten History (The New Press), he lives in Los Angeles.