The Tofts’ home was a mile and a half distant from Godalming’s center, a 30-minute journey on foot. Joshua Toft had a long, lurching stride, kept a brisk pace, and wasn’t one for idle conversation, and so he soon drew far enough ahead of Zachary and John for the two of them to speak together in low voices without concern for being overheard.

The worn leather satchel that contained the tools of the surgeon’s profession bounced against Zachary’s leg as he carried it. Concealed among them was one of the rarest of medical implements, which John Howard kept under lock and key apart from all his others, only bringing it out in circumstances such as these: “midwifery forceps,” which Howard had obtained through means that he refused to describe. The forceps had been a tightly held secret of the legendary Chamberlen family of surgeons for, Howard guessed, 60 years or more; Howard judged that the tool was the key to the Chamberlens’ famous skill in matters of difficult births. “It is a sin to keep such valuable knowledge to oneself, to invent a lifesaving device only to use it to procure oneself an advantage in trade,” he’d said, though Zachary could not help but notice that Howard himself did not choose to advertise his ownership of the forceps, preferring instead to let his local reputation as a veritable miracle worker grow through word of mouth. That Joshua had chosen to solicit Howard’s services instead of those of a conventional midwife spoke well of the forceps’ quiet effect.

“Are you nervous?” John said. “I understand. The event that we are about to oversee was, until recently, considered one at which only women ought to be present. Women preferred to keep their mysteries and rituals to themselves; men preferred not to trouble their minds with them. An agreeable situation for all. But times have changed. The advanced knowledge of childbirth that we have acquired in recent years now places it more clearly in a surgeon’s purview, and makes it the duty of men, no matter what noises midwives might choose to make about the ruination of their womanish ceremonies. The word man-midwife is a tortured locution, and somewhat embarrassing, but I accept it.”

Zachary nodded, eyes resolutely on the road ahead of him.

“I suppose I should speak to you plainly, as Alice would,” John said, dropping his voice lower still as they left the town center, veer- ing from the main road that cut through Godalming as they followed Joshua’s path. “This is knowledge you should perhaps not be granted until you are older, but it is the fate of the surgeon’s apprentice to be initiated into secrets before his time.”

Zachary looked up at John and offered a quick nod, his lips pinched, his face already gone bloodless.

No reason not to be honest, John thought. “Witnessing the delivery of a newborn terrifies men,” he said. “It can be as difficult to watch as a death. All our lives we see the features that differentiate women’s bodies from our own as sources of our pleasure; then, in the moment of birth, their true purposes are revealed. A human head emerges from the place that once served as a sheath for your yard. It is one thing to know it in theory; another thing entirely to see it. And so we speak of the process of birth in the language of miracle and mystery, to avoid confronting the fact that women’s bodies are profoundly different from ours, and are not our own.

“I say that to say this: do not be deceived by any high-flown rhetoric you may have heard in the past about the magic of childbirth. Whatever is about to happen, as strange and even frightening as it may seem to you, will not be a miracle. It is a biological process, as much as digestion, or voiding of the bowels. It is a thing that animals do, and though we stand upright and wear garments and discourse on human understanding, we are, all of us, animals still. To believe that some sort of magic beyond our ken is occurring before your eyes may lead you to unfairly discount your own knowledge, and fail the patient in a moment of crisis. Do you see?”

“I do,” said Zachary, the quiver in his voice signaling that, in fact, he did not. Well, best to see for himself: perhaps the only way for the boy to truly comprehend.

*

A small boy, perhaps two years old, was waiting in the yard outside the Toft home when the party arrived, lying on his back in the patchy grass, gazing up at the late-morning sky. Joshua reached the house ahead of Zachary and John, and from a distance, Zachary saw Joshua’s quick, sharp gestures, his large, fleshy hands like ax blades cutting, signaling commands and criticism; at that, the child slowly roused himself, standing with the slouch of one who shouldered an adult’s burdens and harbored an adult’s resentments, or who at least had already learned to imitate such posture by example. “James,” said Joshua with a desultory wave of his hand as surgeon and apprentice approached, introducing the boy with the inflection one might use for a cow in which one had a small but not undue amount of pride. James looked up at Zachary and grinned, his frock threadbare and dingy, his eyes shining in a face coated with a meticulously acquired patina of dirt.

“Stay outside, James,” said Joshua, “but don’t go far.” He pushed the front door open and entered the house, with John and Zachary trailing behind.

It took a moment for Zachary’s eyes to adjust to the dim interior. The front room was sparsely furnished, and held few if any signs of a leisure life for its occupants: three chairs and a three-legged footstool, all of wood; a tiny table with a few cups and a stack of plates; a tee-totum, lying in wait on the floor to carve its autograph into a parent’s unshod foot sole; no books, unlike the homes of the Walshes and the Howards, where the spines of library volumes advertised the natures of their owners as soon as guests set foot inside. The smell of the house tangled itself in Zachary’s nostrils and wouldn’t let go: the persistent mustiness of unwashed people forever in close proximity; the linger- ing smoke from hearth fire and scorched food; and, beneath that, a faint tang that put Zachary in mind of new blood, the butcher’s-shop odor of meat just stripped of its pelt. He winced, blinking, and looked up to see that John was doing the same.

The bed in the back room, expansive with a wooden bedstead, spoke of better financial times for the Tofts in the past. But it was in bad shape, canting at a slight angle and sagging in the middle, with straw poking through a rent in the ticking. The sallow-faced woman who lay in its center, head propped up on a pillow, bedsheet pulled up to her neck, stared up at the ceiling in silence.

John Howard would ruefully joke to his wife that he wished all of the deliveries would be so considerately prompt.Zachary stood beside John, looking at the woman on her back in the bed as she breathed laboriously through her gaping mouth. It immediately occurred to him, with a certainty of which he was almost ashamed, that she was stupid. She had the face of a dullard: a large, sloping forehead; wide glassy eyes beneath heavy eyebrows; a lumpy, bulbous nose; fleshy, crooked lips; a double chin. Sweaty strands of sand-colored hair peeked out from beneath her faded lace cap. It seemed clear that this was a woman condemned to forever see the world through fog.

“Mary,” said Joshua, nodding at the bed; then, indicating a woman whom Zachary had not yet noticed, standing next to the bed in the shadows: “My mother. Margaret.” Except for Joshua, she was the tallest person in the room, slender and meager, face long, eyebrows thin and arched, dressed in the faded black of someone who had found mourning a suitable habit, and continued it long after it was warranted. She nodded once in turn, her gaze positioned halfway between John and Zachary, as if greetings were best doled out parsimoniously, and this one was expected to be shared.

John Howard stood at the foot of the bed for a minute, looking down on Mary Toft, his forehead furrowed; Margaret and Joshua Toft watched him in silence. “Zachary,” he said at last, in a voice that Zachary found strangely absent of John’s usual surety, “would you retrieve the stool from the other room? And after that, bring a chair for yourself. Just sit and watch today.” He took the leather satchel from Zachary and extracted a bundle from it, wrapped in linen.

From outside came a cheerful squeal from James, the young boy playing at some kind of secret game he’d perhaps just invented.

By the time Zachary had brought the stool for John and the chair for himself, John had pulled Mary down closer to the foot of the bed, her knees bent, the bedsheet draped over her legs to make a sort of tent into which John could peer while seated. Silently, John pointed at the chair in Zachary’s hands and at a space near the head of the bed, next to Margaret, and Zachary carried the chair over and seated himself. He could see John’s face as he continued to look beneath the sheet, though what John himself saw as he examined the patient was left to Zachary’s imagination, filled in by the woodcuts he’d pored over in medical manuals. The place where a man sheathes his yard. But preparing to transform, to become another thing not meant for men’s pleasure.

He felt Margaret Toft touch him as she stood beside him, the tip of a single outstretched finger gliding back and forth along his right shoulder. The gesture was, Zachary assumed, meant to be taken as friendly, but nonetheless it made him break out in goose bumps from head to toe.

“This is . . . unusual,” said John, after a few more moments. “There is bleeding here, but . . . from abrasions. There appear to be several small cuts and bruises. But I see no evidence of what I came here to—”

Mary suddenly screamed then, her left leg kicking in seizure, striking John Howard in the chest and jolting him backward.

“Labor pains,” Margaret said, her finger still gently stroking Zachary’s shoulder. “Since well before sunrise.”

“Strange,” said John, rubbing the sore spot opposite his heart, where a bruise was sure to develop.

From outside they heard the young boy’s wavering wail, as if in answer to his mother’s call.

John continued to examine the woman, as all in the room kept silent. At last, he looked up and at each of the others there in turn:

Joshua, Margaret, and Zachary. Then he stared into the space before him, mouth half open in confusion.

After a brief pause he returned to himself, straightening his back and shaking his head as if to clear it. When he spoke his voice was deeper and a little more imperious than usual, as if to compensate for the short moment of displayed weakness, unbefitting of an expert in his profession. “I know of nothing to do but wait,” he said.

*

They did not have to wait much longer, not more than a quarter of an hour: that evening, John Howard would ruefully joke to his wife that he wished all of the deliveries to which he was summoned would be so considerately prompt.

Joshua Toft had taken to pacing back and forth between one room of the house and the other, head bowed in meditation, his broad-shouldered, gigantic back stooped. His wife continued to lie supine, knees bent, eyes on the ceiling, her body occasionally shifting slightly beneath the sheets as if to ease herself, but otherwise unmoving.

When she entered womanhood, the man who could look past the blight on her face might find a kind of love with her.Zachary dearly wanted to fidget, and knew he could not—he was, after all, a professional, or at least aspired to wear a professional’s mantle, and a professional would not jiggle his knee, or wring his hands, or hammer out a drumbeat on the floor with his feet. He tried to make eye contact with John, who was still seated at the foot of the bed, but John continued to focus solely on Mary. John was silent for the most part, forgoing the patter he usually employed to put patients at ease while he wielded his knives—his one quiet question to Mary about how she was feeling was met with a wordless mumble from the woman that nonetheless managed to convey a deep irritation, as if she had no patience for questions that John ought to have been able to answer for himself.

Zachary had almost convinced himself to slip into a reverie that he was sure would go unnoticed, sinking down in his chair, his eyes half lidded, when he felt Margaret Toft’s hot breath on his ear as she stood behind him, bending over him. Its odor put him in mind of freshly turned soil, or a moldy, waterlogged book.

“Do you want . . . tea?” she asked, her voice a hiss just above a whisper. “It is refreshing. The water: it boils.”

“N . . . no, ma’am,” he replied, sitting up straight again, not daring to turn to look at her.

Slowly, Margaret pulled back from him and rose. “You may soon wish,” she said, her hand oddly heavy on his shoulder, “that you had accepted my generous offer.”

Joshua rambled into the room, peered at each of its inhabitants in turn, swiveled, and strode out once more. John took no notice of him—he continued to watch the woman lying before him, as if attempting to will some kind of change with his mind, wishing for something to happen within her.

“Ma’am?” said Zachary over his shoulder, having second thoughts. “M-may I have some tea?”

“No,” Margaret replied flatly. “You were a foolish boy, and now your chance is gone.”

Unnerved by the exchange, Zachary briefly found himself alert once more, but his mind soon started to drift again. He wondered whether this vigil would make him miss a timely dinner—whether Alice would think to prepare something that could be left to eat cold as soon as he and John returned home, or whether he’d have to starve until supper. (Or perhaps—horrors—they’d still be here come supper-time, and through the night, and into the next day, waiting, waiting, in unending silence.) He thought about the girl with the port-wine stain on her face, from the Exhibition of Medical Curiosities: though he had only seen her twice, she had appeared in his mind ever since at the most unexpected times. Despite the birthmark, or perhaps even because of it, she had almost been pretty, and admittedly, her impish insouciance had held an inexplicable allure. When she entered womanhood, the man who could look past the blight on her face might find a kind of love with her. Perhaps beneath her clothes her skin would be of flawless porcelain; perhaps she’d be secretly piebald from head to toe, which itself might be a peculiar kind of beauty, heretofore unheard of, reserved for a lucky husband’s eyes alone—

Mary Toft screamed.

She sounded as if devils were driving nails into her palms. She began to thrash wildly in the bed, kicking and moaning, arms flailing as she grimaced and punched the mattress with her fists, sending straw flying from its unstitched rent. Her wayward foot nearly caught John Howard across the jaw. “Joshua!” he shouted into the other room, clamping his hands on the surgeon’s tools arrayed on the bed to stop them from spilling. “Come in here! Hold her down—calm her.”

Joshua barged through the door as one of the legs at the foot of the bed gave way, splintering and shooting out from under the frame. The bed dropped with a loud thump, bouncing Mary and coming to rest at an angle, the sheet covering her body flying away, and as Zachary turned his head and closed his eyes, he heard a piece of crockery hit the floor and shatter in the other room.

He saw the soft flesh of a breast; he saw a pale expanse of thigh; he saw a tuft of hair in a crevice.

Joshua ran over to Mary, grabbed both her arms, and wrenched them down, pinning them at her sides; as her legs continued to kick, he bent over, placing his forehead against hers. “Be still,” he whispered as she struggled, his voice even, and unexpectedly tender. “Be still. Be still.” She began, slowly, to settle down, her breaths coming in hitching rasps, and John retrieved the bedsheet from the floor, shook it out, and draped it over her body once again.

Slowly, Joshua released his wife and stood. She kept her arms at her sides, teeth clenched, eyes squeezed shut and leaking tears. Then she grunted something that Zachary couldn’t make out, though it sounded unpleasantly like a curse in another language.

“She says it’s coming,” Joshua said.

John looked up at Joshua, puzzled. “I don’t see–”

Mary grunted again, louder, more clearly this time: “It’s coming.” She threw her head back and shrieked, her body contorting beneath the sheet into a posture almost inhuman, as if her muscles wanted to snap the bones that gave them shape.

Leaning to the side and hunching to examine Mary on the lowered, crooked bed, John Howard shook his head; then, tentatively, he reached with one hand beneath the sheet that covered Mary’s bent knees. He probed gently, his head cocked and his eyes closed; then, as a look of distress suddenly appeared on his face, he made a noise that was somewhere between a yelp and a bark.

He snatched his hand back, bloody, as if he’d been stung. “No,” he said. “No.”

Zachary felt both of Margaret Toft’s hands on his shoulders now, pressing him down in the chair, moving close to his throat.

“No, no, no,” John said, reaching toward Mary again. “No. No, no, no.”

“Sir?” said Joshua, his voice remarkably placid. “What’s wrong?”

“No. No.”

Both of John’s hands were beneath the sheet now as he worked, taking deep, irregular breaths, biting his lip. Beads of sweat broke out in a line along his forehead.

Zachary felt his heart rattling against his rib cage.

John leaned toward the bed, farther than Zachary could understand, as if something beneath the sheet was grasping at the surgeon’s hands, catching him, dragging him in. As Mary brought forth a larynx-tearing screech, John pulled back, nearly losing his balance and falling off his stool.

John looked at the little thing he held pinched between his thumb and forefinger, and began to weep.

It was a severed rabbit’s foot.

Zachary heard the young boy James’s gay laughter from outside the house, immersed in his own private amusements.

“Mary?” Joshua said, his voice barely audible. “Mary.” His wife was glass-eyed, still as stone.

“No,” John whimpered. “No. No.” He deposited the blood-matted hunk of fur and meat with its four tiny black claws on the bed next to Mary with a strangely ceremonial reverence, as if he had no idea what else to do.

Wiping away tears with the back of his hand, John reached beneath the sheet once again.

A hind foot followed to match the forefoot; then John pulled out a thin, glistening rope of intestine, flinging it angrily to the floor. “God damn us all!” he shouted.

Zachary leapt up and tried to run, but Margaret grasped his shoulders and slammed him back down into the chair with an unexpected strength. She pressed her lips against his ear, her spittle coating it as she said, “You should have taken the tea. Now, sit and watch. Boy.”

The rabbit’s head came last, one of its ears broken and listing, its jaws frozen open to reveal teeth seemingly bared in a snarl, the marble of one of its eyeballs popped free from its socket, dangling from the hole by a tendril of muscle. John’s initial shock and horror seemed to have given way, at last, to an uncanny reserve. Carefully, he placed the decapitated head on the bed, next to the two severed feet. He silently performed a last examination of the patient, withdrew, and covered Mary’s legs neatly with the sheet.

Then he stood, nodded once at Zachary, and sprinted from the room, covering his mouth.

Zachary slapped aside Margaret’s hands and followed, colliding clumsily with the wall as he ran. The acrid smell of puke hit him in the face as soon as he burst out of the front room of the house into daylight. He bent, hands on his knees, and joined John in retching, gagging as his guts twisted in his stomach and wrung themselves dry, his half-digested breakfast spattering on the ground.

The boy James stood before them in his dirty frock, pointing at John and Zachary and cackling, dancing an irregular jig to music only he could hear.

Out of breath, Zachary looked over at John, who was wiping a thread of bile away from his mouth with the back of his hand.

“Sir?” he said. “I have a question.”

The ghost of a smile flitted across John’s face, and his red-rimmed eyes crinkled. “Yes?”

“What fee will you charge for this?” said Zachary, rising. “A shilling or two seems, somehow, too little.”

__________________________________

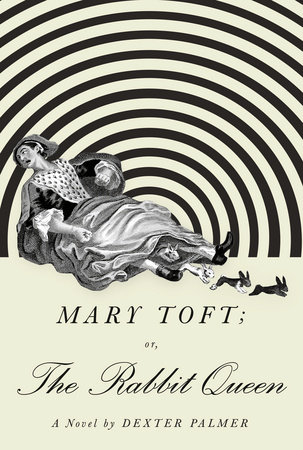

From Mary Toft; Or, The Rabbit Queen by Dexter Palmer. Copyright © 2019 by Dexter Palmer. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.