Martin Luther King Jr.'s Powerful 1960 Letter From

Big Rock Jail

Stephen Kendrick and Paul Kendrick on the Meaning of Protest,

Justice, and Equality

Of all his thousands of notes, letters, memos, telegrams, sermons, speeches, and manuscripts, few are more evocative than a handwritten statement that Martin Luther King drafted in a blue-lined notebook he borrowed from a fellow arrestee. We do not know if he read the whole statement before Judge Webb on Oct. 19, 1960; United Press International quoted him as stating, “I will stay in jail a year if necessary. It is our sincere hope that the acceptance of suffering on our part will serve to awaken the dozing consciousness of our community.”

King’s written statement read, “Mayby [sic] it will take this type of self-suffering on the part of numerous Negroes to finally expose the moral defenses of the our white brother who happen to be misguided and therby [sic] awaken the doazing [sic] conscience of our community.” Working under pressure, King made uncharacteristic mistakes. One of his gifts was an ability to exude calm in the midst of frenzy, a serenity that unnerved his opponents and steadied his followers, but even King was rattled by the events of the day.

And yet he maintained a lofty moral tone in his written statement, asserting, “If you find it necessary to set a bond, I cannot in good conscience have anyone go my bail.” King added, “One of the glories of living in a democracy is that citizens have the right to protest for what they believe to be right.” He continued, “I don’t feel that I did anything wrong in going to Rich’s and seeking to be served. We went peacefully, nonviolently and in a deep spirit of love.” He asserted that they had broken no laws that day. He made clear, “We were there because we love Atlanta and the South.” King laid down his terms, stating he would not offer any appeal because jail was “a way to bring the issue under the scrutiny of the conscience of the community.” At last, he was putting Gandhi’s jail principles into action and honoring James Lawson’s dictum of not posting bail.

Whatever King said did not lighten Judge Webb’s mood. King’s lawyer, Donald Hollowell, sensed that his earlier success was not likely to be repeated. Student leader Lonnie King looked on; he loved watching Hollowell work. When it was his turn to speak for himself, he called segregation “a moral issue that needs to be solved,” and he warned that the protests would continue until the status quo shifted; someone would have to give. Other students also said they would not post bail.

A court staffer interrupted to let Judge Webb know that more students had been arrested at Rich’s Department Store and were on their way over. Webb considered allowing photographers into the courtroom, as was usually his custom, but then informed everyone, “This was a planned demonstration for the purpose of obtaining publicity . . . My courtroom is not going to be used for that purpose.” His attitude toward the students left no doubt that he was not interested in helping their cause by letting them be photographed for national newspapers.

Of all his thousands of notes, letters, memos, telegrams, sermons, speeches, and manuscripts, few are more evocative than a handwritten statement that Martin Luther King drafted in a blue-lined notebook he borrowed from a fellow arrestee.

Outside, twenty students started picketing with signs reading, “We prefer jail to life in hell.” Hearing this, Judge Webb ordered the band of protesters hauled into the courtroom so he could tell them that he found their actions to be a personal insult. The judge said, “If there is anywhere in the world that a Negro has received impartial treatment, it has been in the courts. It is clear in my mind that this act is contemptuous.”

Hollowell interjected that the students’ protest was aimed at their friends being held at the city jail, not their presence in his court. Judge Webb responded that perhaps they had not known they were in violation of his court, but they certainly did now, and if they went back outside to continue, he would punish them to the fullest extent of the law. He concluded his tongue-lashing with a warning: “If you persist in such vile acts, you will lose ground at every step.”

Only one white sit-in participant went before Judge Webb, Richard Ramsay, an organizer with the American Friends Service Committee in North Carolina. While sleeping over at the house of King’s brother, A.D., during the previous week’s SNCC conference, he was intrigued by the direct action being planned. “There was no question about what I was to do,” Ramsay wrote. From his site at McCrory’s five-and-dime on Whitehall Street, he and six students headed for the Magnolia Room at Rich’s, joining students coming in waves from other sites. When Ramsay’s group asked for a table, they were under arrest within seconds and steered to the elevator.

Once at the jail, when the police noticed that a white man was among the group, they pulled Ramsay out to question him as to why he was present. He stoutly maintained that he was with the others. After he was fingerprinted and photographed, an hour passed as he waited alone. Then Ramsay was taken to court with fifteen others, where all refused bond. While Ramsay’s group was fully expecting to go to jail, Hollowell cross-examined the arresting officer to reveal that store officials had asked this group to leave the dining room, not the premises. Based on the judge’s technical reading of the law, he had to dismiss the charges. When the students held a mass meeting at Morehouse later that night, they gave Ramsay a standing ovation for being arrested. He deflected the attention to instead praise all the students in jail that night and would later send a written account of the day’s events to the Georgia Council on Human Relations.

Fifty-two protesters had appeared in Judge Webb’s court by the end of the day. Lonnie was proud of the number of students arrested, with thirty-six ultimately heading to jail—nineteen women and seventeen men—and sixteen students released. Before they could be transported to the new Fulton County Jail, students were held near the courtroom downtown at Fulton Tower—the city jail known as Big Rock. It was a 19th-century Stone Mountain granite structure with a tall, narrow tower extending a hundred feet into the air. Beneath this were the cells, most in abysmal shape—dirt crusted so deep after decades of neglect that it could no longer be scrubbed away, not that this was any priority. This city jail was located across the street from the police department at Butler and Decatur Streets, in the shadow of Georgia’s capitol dome. Only a few decades before, gallows stood on the roof.

The city jail known as Big Rock: it was a 19th-century Stone Mountain granite structure with a tall, narrow tower extending a hundred feet into the air.

In the reeking holding tanks, the students were held alongside drunks, addicts, and others hauled in for various offenses. Prisoners were curious about the bookish, innocent-looking young people who seemed completely unprepared for the environment in which they would have to sleep. The cell looked to have been designed for about twenty people, but they were packed in double that number. There was a toilet situated in the middle of the room, and it was difficult to adjust to using it without privacy. Guards left them sleeping pads that were so rancid that a student wondered if they had been there since the Civil War. One other prisoner wondered why they had volunteered to do this, asking, “You got a chance to bail out, and you don’t bail out?” Their consensus about the activists, it seemed to the student Charles Person, was that “they’re crazy.”

Student protester Blondean Orbert described Fulton Tower as the “smallest, dirtiest, dankest jail.” When the students were about to be moved, Donald Hollowell and King himself were allowed to visit the women. Though they were there to comfort and support them, they also had difficult news to share: their cases might take months more to go to trial, and an eighteen-month sentence for trespassing was possible. They needed to prepare themselves for this eventuality. Hearing this, Orbert fainted.

When she regained consciousness, her roommate Marilyn Pryce and Dr. King were leaning over her, asking if she was all right. She remembered King as a “pleasant, jovial, unassuming man; kind and gentle.” This would be borne out every time she saw him around campus in the years to come, when he would smile and ask, “How’s my little fainting buddy?”

At five in the evening, King, Lonnie, and a portion of the students arrived at the two-month-old Fulton County Jail on Jefferson Street, just north of what is today the Donald Lee Hollowell Parkway. In contrast to the grimy, cold conditions at Fulton Tower, Lonnie could not believe the “brand-spanking-new” gleam their lockup displayed. So many students were arrested at Rich’s that Fulton County needed to borrow beds from adjoining districts to prepare for the students.

King was allowed to call his wife Coretta. He did not speak with his four-year-old daughter, Yolanda, or his two-year-old, Martin Luther King III, saying, “They’re too young; explaining would get too involved.”

__________________________________

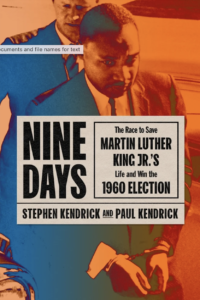

Excerpted from Nine Days: The Race to Save Martin Luther King Jr.’s Life and Win the 1960 Election by Stephen Kendrick and Paul Kendrick. Excerpted with permission by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Stephen and Paul Kendrick

Stephen Kendrick is the author of Holy Clues: The Gospel According to Sherlock Holmes and the novel Night Watch. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Boston Globe, among others.

Paul Kendrick is a writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and USA Today, among others.

Together, they are the coauthors of Douglass and Lincoln: How a Revolutionary Black Leader and a Reluctant Liberator Struggled to End Slavery and Save the Union and Sarah's Long Walk: The Free Blacks of Boston and How Their Struggle for Equality Changed America.