Making Meat Jun, Facing History: Flattening Korean Tradition in Hawaiʻi

Joseph Han on the Militarized History Behind a Favorite Food

Both savory and sweet, meat jun is a Korean dish only found in Hawaiʻi—a thinly sliced piece of beef, marinated and dredged in flour and egg before it’s pan-fried to a juicy crisp. People love meat jun because it leaves you wanting more. A regular plate is often enough for two to share, providing multiple meals and leftovers to spare. A friend recently told me about Dong Yang Inn in Waipahu, which serves meat jun the size of your face.

Where Korean food is an option, in Hawaiʻi it’s relegated to comfort food and grilling, though recently a number of Korean restaurants have been torn down to make way for high-rise condos. Meat jun takes its etymology from a long history of cuisine prepared for the Korean royal court, where jeon, also called jeonyuhwa, describes the preparation of a pancake with either a pan-fried protein, vegetable, seafood, and edible flowers.

This piece of culinary history demonstrates what has long been true: in a largely agricultural country, Koreans have had to be resourceful since before the war and long after its devastation, making budae-jjigae from Spam and other military rations, and adapting meat jun from one militarized context to another.

The first time I ate meat jun was in high school, when I attended a private Baptist preparatory school. Most of my high school classmates were of Japanese descent and came from families who had been around for generations, dating back to the plantation-era Hawaiʻi from which plate lunches originated.

By the mid-19th century, plate lunches became a staple at lunch wagons, trucks, and diners that reflected the tastes of various immigrant communities, serving laborers who needed replenishing, the energy to afford living in a place that continues to cater toward US militarization and tourism over Native Hawaiian values and ways of life, which were central to creating the abundance that sustained the islands and its people for time immemorial.

Meat jun represents what most folks know best about me: to make it in Hawaiʻi as a Korean, you just need to crack a few eggs and take things at face value…

Though meat jun is a favored protein, it’s one of the plate lunch’s many stars to be featured on a bed of rice. When we drove off campus for lunch, we devoured chicken katsu plates, mochiko chicken, loco mocos, and Spam musubis. As one of few Koreans in my class, I witnessed how meat jun became a euphemism for masculinity and a point of stereotype; my classmates asked me if I ate meat jun at home, if we ate kimchee every day.

Though they loved meat jun, they ridiculed me for being Korean, for my appearance and my flat face. Kids would pass me drawings in class, mime slamming their textbooks or palms against their own faces. In their depictions, I was clumsy and kept running into walls, met by accident and misfortune. My face transformed into a pancake, a shovel, a surface devoid of emotion.

Like meat jun, what local consumers found most palatable about the Korean community in Hawaiʻi was the continued flattening of our experiences.

*

In Korea, beef was once consumed only on special occasions. By the twentieth century, our relationship to beef changed as we faced shortages during Japanese occupation, and it wasn’t until the nineties that access to beef became widespread. The same goes for rice, as it was harvested to feed the Japanese empire. The profusion of meat jun in Hawaiʻi, and its preparation, speaks to how consumers want the most from Koreans while asking for the least amount of effort; to know us beyond our offerings, our exchanges skirting on the surface.

In the drawings I’ve received from classmates, the walls I kept running into were put up by those who wished to keep us enclosed, behind the sweet, savory, and thin veneer of assimilation. Meat jun represents what most folks know best about me: to make it in Hawaiʻi as a Korean, you just need to crack a few eggs and take things at face value, but looming behind us stands an ongoing war and the painful division of our peninsula.

Since I wasn’t born in Hawaiʻi, my classmates considered me suspect and untrustworthy. They joked about my being a spy and relative of Kim Jong-Il; that I would one day turn and act out with aggression, an anxiety that would crystallize in 2018 with the false ballistic missile alert, the subject of my novel. I didn’t understand what eating meat jun, and my place as Korean in Hawaiʻi, meant until I faced this history while writing.

Like meat jun, what local consumers found most palatable about the Korean community in Hawaiʻi was the continued flattening of our experiences.

I started to dig, learning how Koreans have been brutalized and crushed by war, referred to as “zipperheads” for the tire tracks left on our faces after being run over by military Jeeps. How the U.S. leveled entire cities and murdered thousands of innocent civilians, dropping 32,000 bombs of napalm burning the northern peninsula to a crisp.

How the militarization and illegal overthrow of Hawaiʻi made the islands a stopping point for soldiers on the way to the Korean War, with the U.S. military continuing to bomb the island of Kahoʻolawe, where they used mock North Korean vehicle convoys and airfields as target practice, which would also inform how they prepared for war in Vietnam. Biennially, militaries around the world gather in Hawaiʻi for RIMPAC to practice war, in turn threatening ocean ecosystems, while finding time for R&R—perhaps getting a plate lunch along the way.

The best plate lunches in Hawaiʻi give you the sense that you’re getting more fixings than you pay for. This principle of extracting and consuming the most you can, for the best value, extends to how most of the world views Hawaiʻi and feeds its tourism industry. The same can be said for the one-dollar per 65-year leases that the U.S. military has settled on with the State of Hawaiʻi in 1964, set to expire in 2029, which includes Pōhakuloa, Kahuku, Poamoho, and Mākua Valley—places where they’ve trained for war, as lands in Hawaiʻi feed the military more than they are allowed to feed its people.

Consequently, Hawaiʻi’s economy depends on US military occupation and tourism, on importing over eighty percent of its food to meet the increasing demand by the tourism sector that replaced the abundance of agricultural lands, such as the farms and wetlands of Waikīkī, drained to create the Ala Wai Canal bordering and zoning out the fantasy we all know today: that there is a price you can pay for paradise, the ongoing spoils of the US playing at war.

In Hawaiʻi we live under the assumption that there’s enough to go around—you’re allotted a select portion if anything at all. So much of living here is premised on masking the presence of war in the everyday. It’s important to consider our cravings and what they hide. War has been on the table far too long, and we are constantly having to partake, both unwittingly and knowingly.

Our appetites may be conditioned by war, but our hunger need not be as insatiable, for war can never have enough of us. I don’t eat meat jun much anymore, but sometimes the craving will strike. As with all things that come in excess, I’d like to hope I know when I’ve had enough.

________________________________

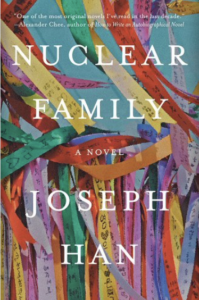

Nuclear Family by Joseph Han is available from Counterpoint

Joseph Han

Joseph Han is the author of Nuclear Family (Counterpoint Press, June 2022) and a 2022 National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree. A recipient of a Kundiman fellowship, he was named a Publishers Weekly “Writer to Watch” in Spring 2022, while his writing has appeared in Nat.Brut, Catapult, Pleiades Magazine, and Platypus Press Shorts. Currently, he is an Editor for the West region of Joyland Magazine and has a Ph.D. in English & Creative Writing from the University of Hawaiʻi-Mānoa. He currently lives in Honolulu.