“Conveying history is difficult. It is hard to escape that amber feeling that things used to not be so bad.”

*Article continues after advertisement

Take any moment in American history, especially in American pop culture, and each feels as messy as the last. Conveying the chaos of history is hard, especially when we have no visual record to refer to, and nostalgia—the sweetest elixir in the world—being what it is.

A grand solution to this predicament is the graphic novel: as an illustrative account of the chaos that has come before, the graphic novel reveals the roots of our fondest memories unlike any other visual medium. Take Vaudeville Theater: it affected everything about American pop culture, but finding out what the culture was like is near impossible for the average person. Or take downtown Manhattan before it was bulldozed into a mega-mall. What was it like? How did these historical moments feel?

To answer these questions longtime cartoonist Mark Alan Stamaty, author of MacDoodle St. (cover detail featured above) and cartoonist for the Village Voice for many years met with authors of A Revolution in Three Acts David Hajdu and John Carey to discuss New York City, their memories, and the lessons of cartooning.

*

John Carey: In A Revolution in Three Acts, we have a lot of New York places.

David Hajdu: The book is essentially a New York story. It wasn’t until after we were pretty far into this that I realized nearly every book I’ve written is about young people in New York trying to find themselves through art and new kinds of creation.

Mark Alan Stamaty: I remember my first morning in New York. A couple days before my first at Cooper Union, I was so excited, and I just went walking. I ended up in Washington Square Park and had a little adventure. I spent years walking around the city; my social life was a lot of wandering around, running into some friend of mine, and then hanging out for a while. So many interactions were just, you know, serendipity, happenstance.

JC: Your book really reminds me of that serendipity. Because these characters—like Helga on the bus, people in delis and eateries—evoke a certain type of spontaneous interaction and eccentricity that only the city can offer. That’s something I’ve never encountered outside the city.

DH: The Village always seemed like a hub of that, because it was where bohemianism as we understood it was. Growing up, I had this romantic, idealized image of the Village from TV and from movies like Greenwich Village with Don Ameche.

The day I came to NYU it felt like I was walking into a dream realized. But a dream that was constructed through popular culture, and then reconstructed in my mind. The impulse we have to romanticize the time when we were there, or the time right before we arrived, is constant. I remember interviewing Village veterans for my book Positively 4th Street and hearing them say, “Well when we arrived in the 60s, the Village wasn’t what it used to be in the 50s.” And then people from the 50s would say, “The Village really isn’t what it was in the 30s or in the 20s.”

JC: But when the three of us showed up in the city, it was kind of a neglected town; we had the ability to appreciate former decades because they were still visible in the city then. You could walk around Times Square in the mid-70s and look up on the second, third floors, and there’d still be signs about dancing girls.

MAS: When I got there in ‘65, there were still these places where you, I never went in one, but you got dance partners, and you could pay them to dance. Union Square was really a soapbox, people would go there and hold forth and give big speeches, and there would be debates about all kinds of politics, politics that came out of the 40s. That went away too.

These graphic novels are movies on paper, so images are equally important, they have to carry their weight.When I got to the Village Voice, we were at 13th and Broadway; at one point in the 80s, they tore down the buildings on the 14th Street side of the block. Before they put up the new buildings, you could see the back of a burlesque theater that predated what they’d torn down. It had pictures of burlesque women painted on the back wall. When I was reading about 14th Street in your book, I thought that must have been what that one was. It was pretty stunning, it brought it together.

MAS: I remember, there’s also the Julian Eltinge Theater.

DH: It was the first and only Broadway Theater named for a vaudeville performer, and it’s still standing. It’s the AMC multiplex on 42nd Street. That’s a building that got some attention a couple of decades ago because it was moved something like 10 or 15 feet. It was put on rails.

MAS: Picture that. It wasn’t in your book, right? Because I was looking at stuff on YouTube about them moving that.

JC: In the book we have a reference that that’s where Abbott met Costello. When they moved the building, they had two giant Abbott and Costello balloons act as if they were pushing it, dressed up in their baseball costumes for the Who’s on First Skit.

DH: And the interior still has remnants of its days as the Eltinge Theatre. There was a beautiful mural painted above the proscenium arch, a hybrid of Romanesque and Greek imagery. There are these buxom women in Roman robes who, supposedly, Eltinge posed for. We’re seeing figures of a man in drag. It’s still there. If you take the escalator to go to the third floor you can see the mural.

JC: Mark, your protagonist, Malcolm, is one of the famous dishwashers in cartoon history. I was a dishwasher in college. Were you ever a dishwasher?

MAS: No, I wasn’t that crazy about dishwashing…

JC: I didn’t go into it because I loved it.

DH: Don’t you have to watch out for your hands as artists? Dishwashing can’t be good for your hands.

MAS: Well, I guess it wrinkles them but it doesn’t hurt your muscles.

I want to ask you a question about your collaboration. It’s beautifully worked out—did you work together on the pacing? How did you work it out?

JC: It’s all David’s construction, he mapped it all out.

DH: Yeah, we worked it out in a somewhat unusual way.

MAS: Did you make panels at all?

DH: Yeah, I did the breakdowns and rough sketches of the whole thing. I was a published illustrator before I published a word of writing, and I know comics, the grammar, and language of graphic storytelling. And John, of course, is a brilliant fine artist.

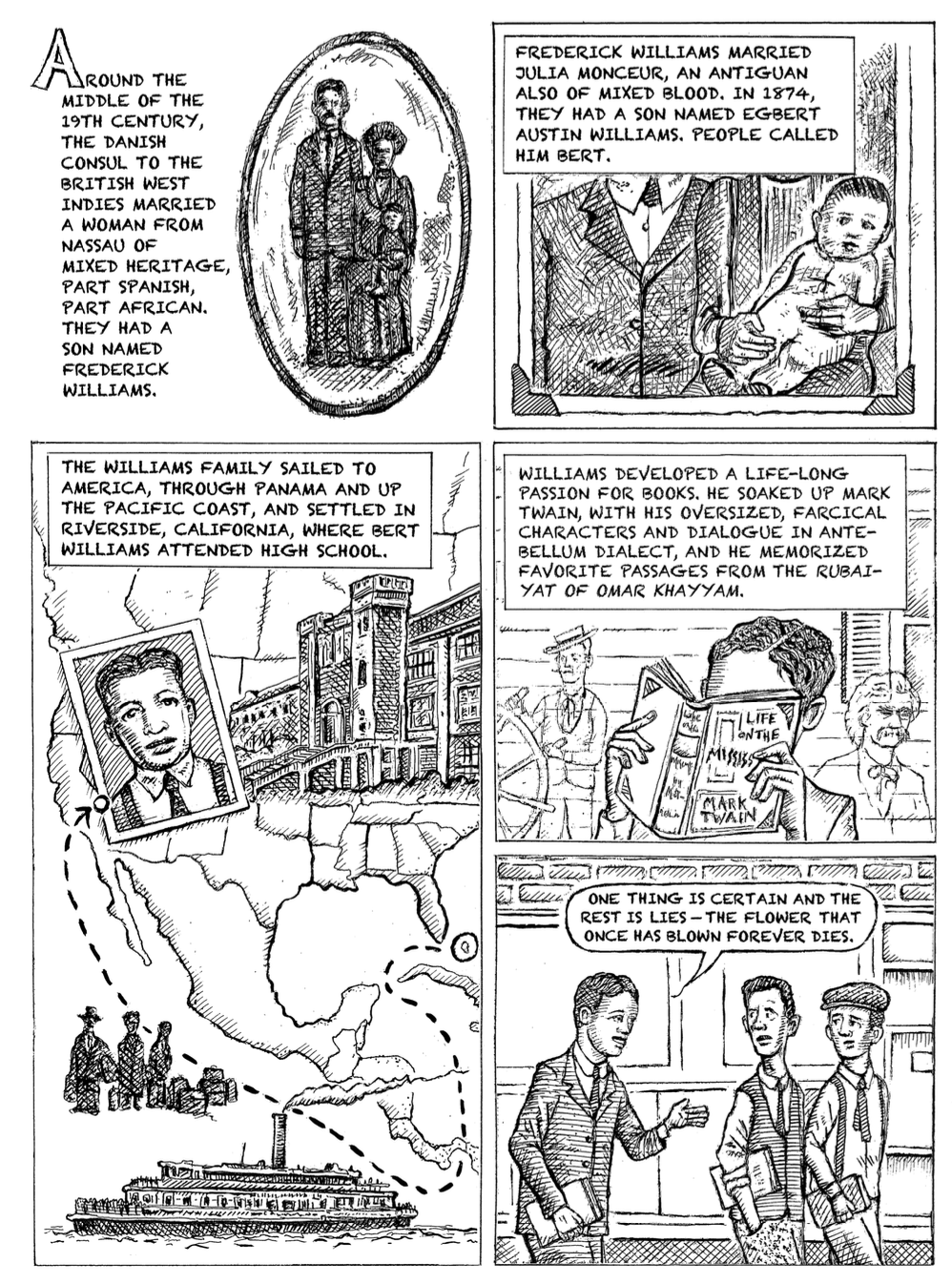

From A Revolution in Three Acts, by John Carey and David Hajdu.

From A Revolution in Three Acts, by John Carey and David Hajdu.

So, I mapped out the whole book—just as I do with my prose books—before we made the first panel. I always write the last sentence of the book before I write the first sentence. Some of the book is dramatic, some is expository, some of it is very visual—there are several pages where we just tell things in visual terms, and I blocked all that out.

MAS: And that’s your job. The hardest part of what I’ve got to do is writing, once I have that, the drawing is another whole bit. It is a job, but if I don’t have it written, I don’t have anything.

DH: John and I had been friends for decades before we did this, and we still are, which is kind of miraculous, because we went through about five years of working together. However, there was one panel where I had roughly sketched Bert Williams: he’s failing, and he’s out of town doing a show, and he’s quite ill, and I drew him sitting in bed and a lawyer comes in and they have a conversation. Then John drew the panel, beautifully, and I said to John, “John, you rewrote that panel,” and he said, “No, I didn’t. I didn’t. I didn’t rewrite it.” I said, “Well, you have them both standing up.” We didn’t argue, but we had an understanding that the visual is part of the writing. If he’s sitting down, that’s part of the writing. Even though there are no words, it’s writing.

MAS: At some point in the 80s, someone wanted to make a movie out of MacDoodle St., so I took screenwriting classes, I wrote the script, but I found out that’s not really what I should be doing. I learned a big part of the writing of a screenplay is the images in place of some of the words. These graphic novels are movies on paper, so images are equally important, they have to carry their weight.

DH: To make sure I don’t sell John short I should point out: the two most beautiful panels in the entire book were ones where he took off from my original notion and went somewhere deeper, richer, and more visually complex. He’s a master.

MAS: I love the detail of the drawings in your book: they are straightforward, clear, and really take you in. My wife, her great-great uncle, Barry O’Neal, was a stage actor, and later a highly regarded director of silent films. She has researched him, we even saw a little of some of his films. But that whole era has a distance because you don’t see HD movies of it. The imagery in your book really gives these things an actual presence, but there’s so much you can’t see because there’s no existing record.

DH: How did you do the research, John? Because you really do bring the era to life.

JC: I did a lot of visual research through Google images, as well going to the Library of Performing Arts at Lincoln Center to find rare images. I think there is also an appreciation of place and locale that informs the book. It might be Tin Pan Alley, 14th Street, Herald Square, a rooftop garden on a Broadway theater or the Eltinge Theater.

I never got the gag-cartoon gene, but a lot of my work has been complicated crowd scenes with little gags.There’s a feeling for New York that we all have, and we bring that to the work. In a parallel universe there’s Mark’s marvelous, eccentric Village. Speaking of Mark’s work, his terrific panoramic panels remind me of Richard Scarry—Busy Town goes to New York.

DH: They have a quality of art brut and outsider art, too. A kind of disruption of perspective, so many things in the same frame.

MAS: I love Jean Dubuffet, especially his colors of a particular period; I love George Grosz. My parents were single-panel gag cartoonists, I grew up around cartoons. I especially loved things with a lot of stuff happening. I would wear a Navy surplus peacoat on my walks, often late into the night… no one would bother me, I could soak it all in. All the activity and vitality, it came into my work.

DH: You evoke it all. Does that come out of growing up with single-panel cartoons?

MAS: I never got the gag-cartoon gene, but a lot of my work has been complicated crowd scenes with little gags. One gag at a time was never for me. What inspired me was Jules Feiffer. At 14, I discovered his book Sick, Sick, Sick, his early Voice cartoons. I realized that I wanted narrative, that’s what I could write and how I could get to something.

With those big scenes, I would do the whole gestalt and get the composition clarified, and then figure out the events within. The panoramas start out like a Jackson Pollock drip painting, then it’s like what’s here, what’s here. I guess there’s a naiveté I like.

DH: It really evokes an outsider sensibility. Almost a kind of madness.

MAS: On the title page of my children’s book Who Needs Donuts, there’s a woman yelling at this bus—there used to be a woman on Third Avenue in the Twenties, and she’d yell at buses. The guru of MacDoodle St. is a character who’s like a Bowery bum, lying on his back, but he’s the dishwashing guru who teaches Malcolm and Helga about Rebecca the Cow, who is the deity of the novel.

From A Revolution in Three Acts, by John Carey and David Hajdu.

From A Revolution in Three Acts, by John Carey and David Hajdu.

And there was an Eddy Reddi. That was his name, I just changed the last letter from Y to I. I met Eddy Reddy on St. Mark’s Place. He was probably in his late fifties, moving a mattress around and trying to get to sleep. I just walked by, but a little later I saw him walking and I went up to him to hear his story, and later I wrote it down. It was a whole story about World War II and all this stuff. I was fascinated by those stories and those convolutions. And the madness, the people with the signs “The CIA is reading my mind.” I loved all that stuff.

JC: It feels like there was a special brand of eccentrics from an earlier generation. I used to go over to Blimpie on Sixth Avenue and at lunch these guys would come in. You’d hear little snippets of conversation, pre-internet days, where nobody at the table would know what to say because one guy said: “Did you know that in FDR’s administration, John Foster Dulles was really a robot?” And you’d think wow this is marvelous, I have to write this stuff down.

MAS: That’s what I did, I always had a pad, and near me was an all-night Bickford’s. It just had a counter that went curling around. I’d hang out there with my pad open drawing people. One night there was an old woman who looked like she was asleep at the counter, and she didn’t move. Then this guy comes in all dressed up in a suit and overcoat—around midnight—orders two cups of coffee to go, the waitress asks him if he’d like donuts with his coffee, and he says no thank you.

Suddenly the sad old woman who’d been asleep woke up, pointed at the ceiling, and said, “That’s right, who needs donuts when you’ve got love.” I went home and I made a sign that said, “Who needs donuts when you’ve got love.”

Then one day I’m sitting in my apartment, looking around, and I thought, “I want to find something meaningful,” and I looked at the sign on my wall and thought, “I want to make that woman famous.” That was where Who Needs Donuts came from.

JC: Now I regret that I didn’t write a book called John Foster Dulles is Really a Robot.

DH: It’s not too late.

JC: Hey, speaking of eccentrics, has anybody said that your character Darius is a pre-Trump character?

MAS: Darius was based on my geometry teacher in high school—nobody has said that but I think it’s a fair conclusion. My geometry teacher, some people thought he was maybe a nice guy. I don’t know. He came into class the first day and said in a very quiet voice, “I’m going to conduct the class at this level of volume of my voice and if you miss anything you’re responsible.” I wasn’t good at math, and he struck me as a cold, rigid figure. So that’s what popped into my head for a villain when I did MacDoodle St.

JC: Do you think you’re going to revisit Helga, Hugo, Gustaf, and the rest of the gang?

MAS: I don’t know. I kind of always wanted to, but then I was kind of in a different place. I’m working on graphic novels now, I’ve sort of got three that I started and I’m just hoping I can keep finding the muse. I would have loved to just keep with those guys for quite a while, but I guess I was on to something else. You have to go where it all takes you.

JC: Are the graphic novels nonfiction?

MAS: There’s one that’s memoir-esque. It’s very personal… I renamed myself and other things like that. And then a cowboy one that I have about 60 pages of, because I grew up watching westerns. The last one is, I hate to use this word, but maybe it’s the appropriate word… zany. MacDoodle St. was the closest I came to the feeling I’d like in this new novel, but I want to go a lot further with it. I often write chapter ones that are in the spirit of that (I have many chapter ones). I may be combining them to make this. The closest word I can think of is zany.

JC: Kooky.

MAS: Yeah it’s kooky. I want to write a kooky novel.

DH: We need more kooky novels.