Magnificent Obsession: On Black Humor and the Necessary Lessons I Learned as a Cartoonist

Charles Johnson Recalls His Personal Journey from Unpublished Hopeful to Professional Artist and Celebrated Author

When I was 15 years old in the early 1960s, I studied with the cartoonist and writer Lawrence Lariar in his two-year correspondence course. He was prolific (something I admired), the author of more than a hundred books, some of which were murder mysteries he wrote under pseudonyms. He was the cartoon editor of Parade magazine, and the editor of the Best Cartoons of the Year series; at one time he was an idea man at Disney. He was liberal, Jewish, and lived on Long Island, where he delighted in infuriating his neighbors by having black artists over to his house for drawing lessons. I found Lariar when I was reading Writer’s Digest profiles of famous cartoonists—my heroes—and came across an ad for his course.

The only serious disagreement I ever had with my father was when I announced to him that I planned on a career as an artist.

My dad was quiet for a few seconds, and then said, “Chuck, they don’t let black people do that. You need to think of something else.” His words shocked me, and I could not accept them, but they have haunted me all my life, for they were the product of what he had experienced as a black man living through America’s grim era of racial segregation.

If I couldn’t draw or create, I didn’t want to live. I didn’t want to think of something else. I wrote Lariar a letter, explaining what my father had said, and asked him if he agreed. I never expected to receive a reply, but Lariar fired back a letter to me within a week in which he said, “Your father is wrong! You can do whatever you want with your life. All you need is a good teacher.”

My father backed down when I read him that letter, admitting that when it came to the arts in the 1960s, he didn’t know what the hell he was talking about. He paid for my lessons with Lariar from 1963 until 1965, the year I became a professional, paid artist when I published my first illustrations in a Chicago magic company catalog. (I framed one of those first dollars and still have it in my study.) I began publishing short stories in the literary section of my high school newspaper, the Evanstonian, as well as drawing sports cartoons and a satirical comic strip titled Wonder Wildkit, a spoof on Wonder Wart-Hog that I made with a friend (he wrote, I drew). In 1966, that comic strip and one of my many sports cartoons both received second-place awards in a national contest for high school cartoonists sponsored by Columbia University’s School of Journalism. Some of that high school work is anthologized in First Words: Earliest Writing from Favorite Contemporary Authors, edited by Paul Mandelbaum (1993).

During those two years of study with Lariar, I twice took a Greyhound bus from Illinois to New York; each time I stayed with my relatives in Brooklyn for a week and, after calling editors at different places to set up visits, I pounded the pavement in Manhattan with my “swatch” of cartoons (samples), going from one publishing house to another, looking for work. It was during one of those meetings that I met a young editor and cartoonist, Charles Barsotti, whose simple but endearing cartoons appeared regularly in The New Yorker, which at the time had a notorious history of not using the work of black cartoonists.

In 1996, The New Yorker published a special “Black in America” double issue, which featured the work of 13 “gag artists,” only one of whom was black; eight black people who submitted work were rejected, and the magazine’s cartoon editor, Lee Lorenz, admitted that The New Yorker’s stable of cartoonists at the time was still entirely white. Sometimes I’ve wondered if my father’s original warning to me contained an element of truth.

Barsotti was undoubtedly aware of the whiteness of cartoonists whose work appeared in that publication. (Lariar once complained to me how his work was always turned down by The New Yorker, a publication where I never submitted my own work.) After one of my trips to New York, Barsotti wrote to tell me that as a young black cartoonist I could work with racial material that “an old white guy” like him and his friends wouldn’t be able to touch. It would be a few years, however, before his suggestion fully took hold of me.

If I couldn’t draw or create, I didn’t want to live.

I always visited Lariar during my trips to New York. He fixed me lunch when I was in my teens and dinner when my wife, newborn son, and I visited him during my time in the philosophy PhD program at Stony Brook University (as an undergraduate at Southern Illinois University I was a journalism major who took loads of philosophy courses, then after graduation immediately began the long journey to a master’s degree and doctorate in that field). He loaded me up with original art from the days when he had a syndicated strip (he wrote, someone else drew it), and regaled me with stories about the comic artists I so admired. During my undergraduate college years, I sent him copies of editorial, panel cartoons, comic strips, and illustrations I published. Between 1965 and 1972, hundreds of these drawings ran in Midwest periodicals like the Chicago Tribune, black magazines such as Jet, Ebony, Black World, Players, and a St. Louis magazine called Proud, and he always wrote back something encouraging.

I drew furiously from 1965 to 1969—cartoons, illustrations, and comic strips (The God Squad, Trip) for my college newspaper, the Daily Egyptian; editorial cartoons for the Southern Illinoisan in Carbondale, Illinois; one-page scripts for Charlton Comics; and a design for a Southern Illinois commemorative stamp. I was obsessed in my teens with being published. The art supply store was my second home. I was always ready to draw anything for anyone who would put my work into print. The challenge for me was always, “What can I draw next?” because when I figured out how to draw something, it almost felt as if I owned it.

In January 1969, I went to a poetry reading by Amiri Baraka, one of the principal architects of the Black Arts Movement, which was the cultural wing of the Black Power movement until the mid-1970s. During the Q&A he refused to take questions from white members of the audience. I thought that was unnecessarily rude, but something he said to the black students struck me thunderously, as if he was talking directly to me. He said, “Bring your talents back home to the black community.” I began to wonder: What if I directed my drawing and everything I knew about comic art to exploring the history and culture of black America? I suddenly returned to what Barsotti had suggested to me four years earlier—to focus my work on black humor.

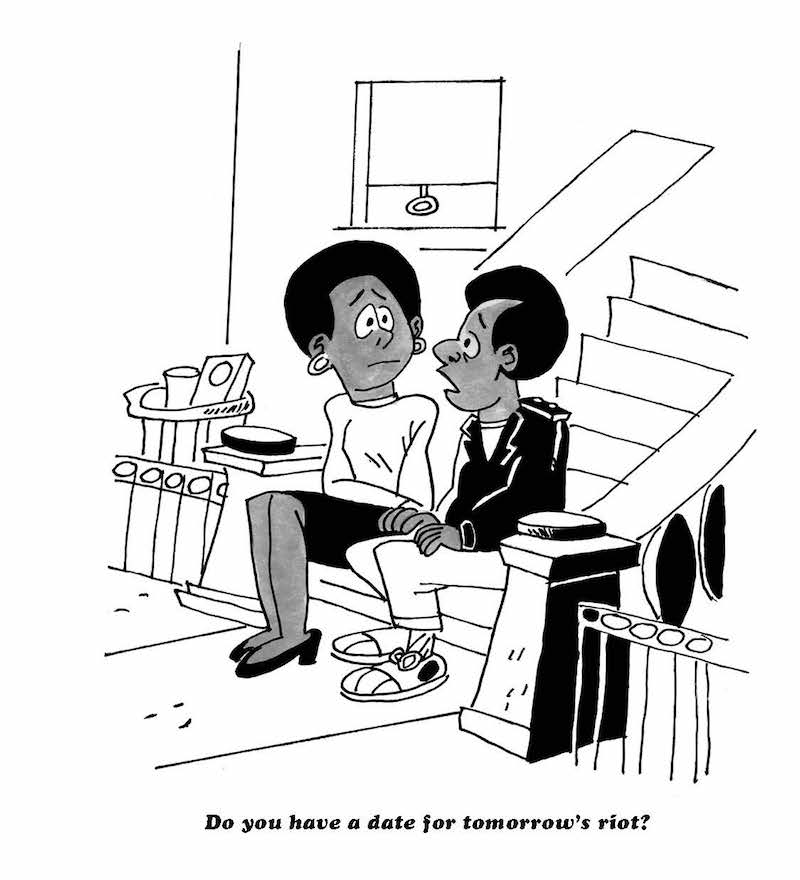

From Black Humor, Johnson Publishing Company, Inc., 1970

From Black Humor, Johnson Publishing Company, Inc., 1970

I remember walking back to my dormitory in the rain from Baraka’s reading, dazed by what he’d said. I sat down before my drawing board, my inkwell, my pens. I started to sketch. I worked furiously for a solid week, cutting my classes. The more I drew and took notes for gag lines, the faster the ideas came. After seven intense days of creative outpouring, I had a book, Black Humor. My only problem was I didn’t know where to send it. But the school of journalism offered me an internship for the coming summer at the Chicago Tribune. There, I worked on the newspaper’s Action Express public service column and occasionally did a drawing for it. One day I had an eventful discussion with the book editor, Bob Cromie, and told him about Black Humor. He suggested I show the book to publisher John H. Johnson down the street at Ebony magazine, which I did. Before the summer of 1969 was over, he accepted it for publication in 1970.

That same year I hosted the PBS how-to-draw show Charlie’s Pad, with 52 15-minute lessons based on Lariar’s two-year course, and inspired by a TV spot he did in the 1950s or 1960s when at the end of a news program he drew something funny about that day’s headlines. There was no causal connection between Black Humor and Charlie’s Pad. The television program was a separate project. In 1967 Congress created the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. That led to “educational television” stations around the country needing content for programming. I didn’t know that in 1969, but one day when I was in my dormitory room feeling bored, I wrote to the local station, WSIU-TV, and asked if they’d be interested in my doing a cartooning show for them. They were, because it was cheap and easy to do—all they needed were two cameras and me at a drawing table. That show was broadcast around the country for about ten years.

I produced a few other books of cartoons after that. The second, Half-Past Nation Time (1972), was done by a fly-by-night California publisher called Aware Press, which disappeared as soon as they sent me my author’s copies—I have only one copy now, and it can otherwise only be found these days in library rare-book rooms. I did an entire book of cartoons on slavery, I Can Get Her for You Wholesale, which the publisher of Aware Press disappeared with, and another devoted entirely to Eastern philosophy, It’s Lonely at the Top. Although never published as a book, these drawings have appeared here and there in different magazines; seven appear in Buddha Laughing: A Tricycle Book of Cartoons (1999).

No creative pleasure is greater for me than the physical (as well as mental) process of comic art.

My work as a cartoonist eventually gave way in the early 1970s to the time required to earn my doctorate in philosophy—and to the years I spent writing novels and short stories, essays, screenplays, literary criticism, and Buddhist-oriented books and articles, as well as teaching English and creative writing for 33 years at the University of Washington. What I taught can be found in The Way of the Writer: Reflections on the Art and Craft of Storytelling (2016). When Lariar read my debut novel, Faith and the Good Thing (1974), he wrote me a letter, saying, “You have ‘the touch.’” But I could never stop drawing.

For a period in 1971, while I was working on my master’s degree, I finished five single-panel cartoons a day (I’d usually sell five of the 25 I did during the week, which was enough to pay for groceries), I did draw birthday cards for my kids as they were growing up, and these days work on illustrations requested by friends and former students. After my third novel, Middle Passage (1990), received the National Book Award for fiction, I again leaped at every opportunity to draw something—even for free, which I know distressed my literary agents. For a time I drew cartoons for the Quarterly Black Review of Books, and for a free New York literary journal called Literal Latte. When my daughter Elisheba suggested that we do a children’s book together, I seized the chance to cowrite with her what are now three books in the Adventures of Emery Jones, Boy Science Wonder YA series simply because each book gave me a chance to draw around twenty illustrations.

After 55 years of steadily publishing stories and drawings, I still need to externalize on the page images and ideas that exist only in my head where no one can see them. As a writer, I think visually, and no creative pleasure is greater for me than the physical (as well as mental) process of comic art. Other writer/artists have felt this way—for example, John Updike once confessed that none of his literary work brought him the deep satisfaction he experienced as a cartoonist during his college years. I think I know why he felt that way. I love the fibrous texture and feel of drawing paper beneath my fingers. I love, too, the odor of India ink; working with a T-square and triangle; playing with push pens and masking tape, with hard and soft erasers (remember: all real art involves, to some degree, play); the messiness of white correcting fluid, different pens and brushes, the concentration necessary for doing sketches or early drafts to arrive at a balanced composition, one deliberately and deceptively simple with strong, bold outlines yet occasionally detailed in respect to costuming, props, hairstyles, shading, etc. I especially relish the inking phase in the wee hours of morning as I’m listening to soft jazz.

One might ask, what causes this lifelong addiction to drawing comic art? The answer, I believe, is a time-honored reply: We think in pictures. Like music, the content of a drawing can be universally recognized; it cuts across language barriers, and can be “worth a thousand words.”

__________________________________

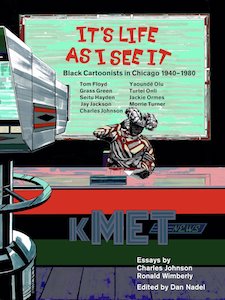

Excerpted from It’s Life as I See It: Black Cartoonists in Chicago 1940–1980. Used with the permission of the publisher, New York Review Comics, an imprint of New York Review Books. Copyright © 2021 by Charles Johnson.

Charles Johnson

Dr. Charles Johnson is a novelist, essayist, literary scholar, philosopher, cartoonist, short story writer, a MacArthur fellow, winner of the 1990 National Book Award for his novel Middle Passage, and recipient of an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award for Literature.