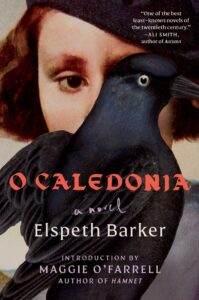

Maggie O’Farrell on Elspeth Barker’s Modern Scottish Classic, O Caledonia

“This book, then, is the equivalent of a literary phoenix—rare, thrilling, one of a kind.”

We begin with a corpse. Sixteen-year-old Janet is sprawled “in bloody, murderous death” beneath the stained-glass window of her Highland home, dressed in her mother’s “black lace evening dress.”

This is murder most foul and, unfortunately, there is no shortage of suspects: Janet, it would appear, was not a popular child. Her family bury her with haste because “she had blighted their lives…She was to be forgotten.” The sole mourner is Janet’s jackdaw: he searches for her “unceasingly” and then “in desolation, like a tiny kamikaze pilot, he flew straight into the massive walls of Auchnasaugh.”

Despite this opening, O Caledonia is not a whodunnit; do not expect a tense search for a criminal. What you are holding in your hands isn’t an investigation of who killed this unfortunate girl: Elspeth Barker is too deft and subtle for that. It’s an account of Janet’s life, from birth to early death, taking in sibling bonds and betrayals, parental intolerance, the horrors and discomforts of adolescence, and the saving grace of books.

The world you are about to enter is one of prickly tweed coats, of grimly strict nannies, of irritatingly perfect younger sisters, of eccentric household pets, of enormous freezing castles. It is one where girls are considered to be merely “an inferior form of boy” and Calvinist propriety is thrown into relief by the seductive wildness of the Highland landscape.

O Caledonia is not a whodunnit; do not expect a tense search for a criminal.

The news that the novel was going back into print and into bookshops has been met by those in the know with unadulterated glee. I’m not ashamed to say I clapped my hands. O Caledonia is one of those books you proselytize about; you want to beckon others aboard its glorious train. I have bought numerous copies as presents, pressing them into people’s hands with an exhortation to read without delay.

I once decided to become friends with someone on the sole basis that she named O Caledonia as her favorite book; I’m happy to report that it was a decision I’ve never had cause to regret. When I taught creative writing, I would read aloud the opening chapters to my students and I would constantly break off to say, “Are you hearing this? Do you see how good that image/word choice/sentence construction is? Do you?”

Barker was born Elspeth Langlands in Edinburgh, 1940, to two teacher parents. The eldest of five siblings, she grew up in the neoGothic Drumtochty Castle, Aberdeenshire. Her father purchased it from the king of Norway, or so family legend had it, with a view to running it as a prep school. The children lived there during term time, like Janet in the novel, studying alongside the paying pupils; holidays were spent by the sea, in their house in Elie, Fife. Elspeth gained a place at Oxford University, where she read Modern Languages. In her early twenties, she married the poet George Barker; they had five children.

Linguistic skill and deep semantic pleasure are evident in everything she writes. You can open this book at random and within seconds light upon a phrase that is not only elegant but shiveringly exact. A furnace “which throbbed and quivered in the boiler room.” Tragic Cousin Lila, who likes to identify fungi, covering “floor space in great sheets of paper dotted and oozy with deliquescent fruit bodies.” Janet’s hatred of the sea is explained thus: “There was so much of it, flowing, counter-flowing, entering other seas, slyly furthering its interests beyond the mind’s reckoning; no wonder it could pass itself off as sky; it was infinite, a voracious marine confederacy.”

In 1990, Alexandra Pringle, then a publisher at Virago, commissioned the novel based on a handful of “wonderful vivid, funny pages.” She says: “When O Caledonia came in it was perfect. It needed no editing. It was simply there in all its dark and glittering glory. And then followed two marvelous years of extraordinary reviews and literary festivals and prizes.” Elspeth herself, Pringle describes as “wild, darkly beautiful, and incredibly funny and clever.”

I first encountered Elspeth at a distance, in the mid-1990s, when I was working as an assistant on the book pages of a newspaper. Elspeth was spoken of in hushed, reverential tones; she was one of the most valued contributors. Imagine my surprise, then, when I learned that this exulted reviewer’s work arrived, not by email or fax, but by post, in heavily sticky-taped old envelopes that often had shopping lists scribbled on the back. Inside were folded pages of prose in a flowing, looping script, and it was my job to input them into the computer system, to decipher and type them up.

What she wrote was faultless: always incisive, unfailingly generous, piercingly intelligent. Occasionally, her handwriting would prove elusive and then I would have to phone her up for clarification. These calls were the highlight of my job, an all-too-welcome break from the tedium of office life. If the phone was answered— which was never a given—there would be Elspeth, her voice slightly husky, her vowels from another era, her diction punctuated by regular draws on a cigarette.

Before the task in hand, there was always a bit of chat, about life in Norfolk, walks taken, parties attended, her grandchildren, the health of various beloved pets. It was not uncommon for the call to include a recitation of Greek poetry or for it to be truncated by a startled exclamation: “Oh, I must ring off,” she shouted once, “the pig’s got into the kitchen.”

On one level, it’s possible to read O Caledonia as autobiographical fiction: the strict upbringing in a windy castle, the fiercely bright and non-conformist heroine who finds love and companionship only in the animal kingdom. But this would be a reductive take on a skillful and brilliant novel because O Caledonia is a book that at once plays with and defies genre. To give it that most vague and limiting of categories—the coming-of-age novel—is to miss its point and to underestimate the ingenuity and droll subversion Barker is employing here.

O Caledonia is one of those books you proselytize about; you want to beckon others aboard its glorious train.

In these 200-odd pages of prose, she gives the nod to a number of literary genres while deftly navigating her way around and past them. There are more than a few allusions to the Gothic Novel, to classical myth, to Scottish literary tradition, to nature writing, to Shakespeare and autofiction. If O Caledonia has literary parents, they might be James Hogg and Charlotte Brontë or Walter Scott and Molly Keane. Literary siblings might be I Capture the Castle or the Cazalet Chronicles, and not just because they are books which detail the travails of living in a large and dilapidated house. Janet has much in common with their young anti-heroines—unloved, unlovely, distantly parented, too intelligent for the milieu into which they are born.

So, on the one hand, O Caledonia is about a young girl growing up, but, on the other, it isn’t. Its themes and reach go beyond this. Janet’s struggle is universally that of the individual against the forces of authority: it is the fight to maintain one’s identity against powerful odds. It is the conundrum of how to become the person you need to be while all those around you desire you to be someone else.

Janet’s antagonists are first her parents, then her siblings, then her peers; we cheer her on as she resists the pressure to conform, to squash herself down. She learns not to say to her classmates, “I love the subjunctive… It’s subtle, it makes the meaning different… I call my cats subjunctives,” while still maintaining her individuality. “Only at night under the bedclothes did she allow herself the tiny luxury of muttering two expressions favored by characters in Greek tragedy.”

Towards the end of the novel, it becomes necessary for Janet to grapple with a new opponent: the opposite sex. “A dreadful thing happened. Knobby protrusions appeared on Janet’s chest. They hurt. The boys noticed them…and liked to punch them.” A summer visitor who accosts her more insistently, “twirl[ing] a dreadful dark pink baton out of the front of his shorts,” is summarily shoved into a giant hogweed patch.

O Caledonia is the only novel Barker has ever published. “To have written this dazzling beauty,” says Pringle, “is a fine achievement of a lifetime.” We have the wealth of years of journalism but this is the only fiction of hers in print. This book, then, is the equivalent of a literary phoenix—rare, thrilling, one of a kind. Read it, please, with that knowledge.

I confess that I harbor a frail hope that there might be a secret pile of pages in a certain idiosyncratic handwriting somewhere in a desk drawer in Norfolk. If this is the case, I am more than happy to once again offer my typing services for their transcription.

__________________________________

Excerpted from O Caledonia by Elspeth Barker. Introduction copyright © 2021 by Maggie O’Farrell. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Maggie O'Farrell

Maggie O’Farrell is the author of the #1 Sunday Times (London) bestselling memoir I Am, I Am, I Am and eight novels, including The Distance Between Us, which won the Somerset Maugham Award; The Hand That First Held Mine, which won the Costa Novel Award; Instructions for a Heatwave, shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award; This Must Be the Place, shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award; and Hamnet, winner of the 2020 Women’s Prize for Fiction, the 2020 NBCC Award for Fiction, the 2020 Waterstones’ Book of the Year, and was the Fiction Book of the Year at the 2021 British Book Awards. She lives in Edinburgh.