Luke Mogelson on the Far-Right, the Militia Movement, and the Threat of Trumpism

And Other Lessons From His New Book The Storm is Here

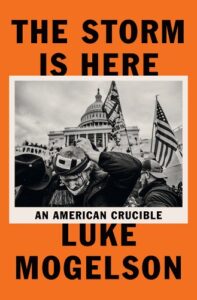

It’s no secret that right wing extremism has been on the rise over the last few decades in the United States, a militia-based movement that came to forefront of national consciousness on January 6, 2021, as an unruly mob stormed the Capitol Building. We talked to Luke Mogelson, author of The Storm is Here: Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, Three Percenters, about what it all means, and where it might be going.

*

Lit Hub: There are a number of far-right groups you report on in your new book, The Storm is Here. If there is an organizing principle with these groups, what do you think it is?

Luke Mogelson: A sense of dispossession: the belief that something belonging to them has been usurped or stolen. Since militias mobilizing against public health measures rejected the scientific rationale for lockdowns, what they had lost was not a sacrifice for the public good—it was a theft. After George Floyd was killed, Trump characterized the nationwide demands for racial justice and police accountability as an effort by state enemies to “wipe out our history, defame our heroes, and erase our values.” The subsequent campaign to overturn the results of the 2020 election was called “Stop the Steal.” Inside the Capitol on January 6, many of the rioters attacking law enforcement chanted, “Take it back!”

Patriot militias, the Proud Boys, the Oath Keepers, and the Three Percenters all see themselves as “defensive” groups, engaged in protecting vulnerable Americans from oppressive forces who threaten to deprive them of one thing or another—their land, guns, freedom, job, voice, heritage, religion, or vote. This is why conspiracy theories are so prominent on the far right. They project menace onto the world and endow benign events with malicious intent.

LH: In the book you have a line, after relating your experiences with war and violence in Iraq and Syria: “Were large scale violence to erupt in the US, it would be something different: A war fueled not by injury but by delusion.” Can you expand on that?

LM: Right-wing militarism emerges from a sense of victimhood. Yet right-wing militants are overwhelmingly white heterosexual Christian men—no doubt the least victimized demographic in American history. Those who exploit right-wing fear and anger for political or financial gain resolve this paradox by inventing fictional grievances and phantoms of oppression.

These inventions run the gamut from nativist propaganda (an illegitimate Black president, an invasion of Muslim and Hispanic immigrants, an Antifa insurgency) to outlandish conspiracy theories (a pandemic engineered by Bill Gates and George Soros, a cabal of Democratic pedophiles overseeing an international sex-trafficking industry, a Venezuelan plot to flip electronic votes from Biden to Trump), but they are all illusory.

In contrast, every civil war I’ve covered has been premised on real grievances, real oppression, real violation. When I’ve asked frontline soldiers on any side of a given civil conflict why they were risking their lives, they have almost always responded with concrete, rational answers, be it the Talib whose village was occupied by foreigners or the Yazidi whose daughter was enslaved by ISIS or the Syrian whom the regime kidnapped and tortured.

The recent invasion of Ukraine, on the other hand, offers an interesting comparison with our situation in the U.S. While Ukrainians are obviously resisting genuine oppression, Russians have fabricated a slew of fictional grievances to rationalize their unprovoked aggression (from accusing Ukraine of developing nuclear and biological weapons to characterizing its leaders as genocidal Nazis). Tellingly, many pro-Trump pundits and activists in the US, such as Tucker Carlson, have embraced and amplified these falsehoods while expressing their admiration and affinity for Vladimir Putin.

LH: Was there ever a disconnect between what people said in public and at rallies, and what they said to you personally? How did they react to you as a journalist?

LM: Almost everyone I met was polite and forthcoming with me. This has generally been my experience wherever I’m reporting. Most people who are willing to pick up a gun or take to the streets believe deeply in the righteousness of their cause, whatever it might be, and so are more than happy to speak with journalists. I was consistently impressed by the level of passion and conviction that Trump supporters displayed—a zeal seldom matched by the left. The only comparable fervor that I have witnessed on the other end of the political spectrum was in Minneapolis after the death of George Floyd.

At one point inside the Capitol on January 6, I watched a group of Trump supporters confront a line of officers. “I will not let this country be taken over by globalist communist scum!” one of the Trump supporters screamed. He was hoarse and trembling. He could not comprehend why the officers would impede such a virtuous undertaking. “You know what’s right,” he told them. Then he gestured at the mob. “Just like these people know what’s right.”

To be clear, I am talking here about the foot soldiers. A separate question is whether or not the generals—Donald Trump, Steve Bannon, Roger Stone, Enrique Tarrio, Michael Flynn, Stewart Rhodes, Nicholas Fuentes, Alex Jones, etcetera—are disingenuous. To what extent do they believe the lies that they purvey, and to what extent are the lies a cynical ploy for them to retain power or make money? Are they drinking the Kool-Aid or just serving it?

LH: As a journalist who was there for so much of the unrest, what did you think of the January 6 hearings?

LM: My reporting focuses on what was happening on the ground, at the front of the protests and riots, inside the mobs, and among the people who were converting propaganda into physical action. So I was very interested in the testimony of White House and campaign officials who addressed the question I raised above: Did the architects of that propaganda actually believe it themselves?

According to the witnesses, the answer is no, they did not. Virtually nobody in Trump’s orbit—not his lawyers, not his chief of staff, not his attorney general, not his advisors, and not his own daughter and son-in-law—appear to have put any credence in the claims of fraud that he was peddling to his followers, so it’s difficult to imagine that Trump did either.

While it was encouraging to hear stalwart Trump allies publicly disavow these claims, it was also somewhat aggravating to see them lionized by the committee members as courageous defenders of democracy and loyal guardians of the Constitution.

I’m glad that Mike Pence refused to unilaterally overturn the election, and that Arizona House Speaker Russell Bowers would not appoint false electors from his state, and that Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger declined to conjure 11,780 votes for Trump out of thin air—but not actively participating in a coup is a pretty low bar for heroism. Furthermore, many of the people who turned against Trump on or after January 6 were complicit in fomenting—over the course of 2020 and the previous four years—the environment that made that day possible.

LH: Was the Capitol Insurrection a culmination or a beginning?

LM: Neither. The MAGA movement is just the latest iteration of a current in American culture that has assumed various guises throughout our history and will surely continue to evolve with it. Barack Obama’s election in 2008 spurred what came to be known as the Patriot Movement: a loose federation of hundreds of armed groups—among them the Three Percenters and the Oath Keepers—organized on the pretext of gun rights but often hostile to Muslims, immigrants, and the LGBTQ community.

During the 2016 primary campaign, Patriots were profoundly energized by Donald Trump’s candidacy, and, along with their political analogue, the Tea Party, they helped propel him to the Republican nomination. This alliance only strengthened over the next four years, as Trump embraced and propagated a range of Patriot conspiracy theories in order to dismiss the various scandals, investigations, and accusations that plagued his term. So Trump tapped into evolving forces that long predated him—but he also turbo-charged them.

Over the course of 2020, I witnessed anger with COVID‑19 policies grow into a fanatical anti-government movement, which became a militarized opposition to demands for racial justice, which became an organized crusade against democracy.

There was an opportunity after January 6 for America to reckon with the threat that Trumpism and right-wing extremism present to the country, but Republican leaders instead chose to distort, downplay, and deny what took place that day, making it yet another grievance in their never-ending saga of dispossession. Many conservatives today feel that they are the true victims of the Capitol attack: that hundreds of Americans engaging in a “normal” protest have been unfairly persecuted by the Justice Department, that Ashli Babbitt was executed, that the Select Committee is a partisan effort to smear Republicans, that the 2020 presidential election was stolen, and that our democratic process is rigged against them.

LH: How do we combat a well-funded, integrated media network that provides conspiracy as entertainment to millions of Americans?

LM: I wish I knew.

LH: Do you see anything on the left that parallels the militia movement of the right over the last 30 years?

It’s easy to find what appear to be parallels because right-wingers, in relentlessly casting themselves as victims of persecution, tend to appropriate the rhetoric and style of actually oppressed communities. Their abhorrence of the federal government, for instance, is often rooted in a kind of revanchism that resembles Indigenous reclamation campaigns.

In 1968, Sioux and Ojibwe activists from Minneapolis launched the American Indian Movement, or AIM. Much like the Black Panther Party and its “cop-watchers,” AIM organized neighborhood patrols to monitor and document law enforcement behavior. (Nationally, Native Americans have consistently suffered from police brutality at higher rates than any other race or ethnic group.)

One night while covering the protests and riots in Minneapolis after the death of George Floyd, I was following demonstrators down a main boulevard when we came upon half a dozen armed men and women wearing T-shirts that read: NATIVE AMERICANS WERE NEVER HOMELESS BEFORE 1492. A middle-aged man had a revolver on his hip, a machete in a leather sheath, and a shotgun balanced over his shoulder. “We’re on the same team, but we can’t allow what little we have left to go,” he told the protesters.

After the first day of riots, when a number of buildings had started going up in flames, old AIM activists and other leaders had put out a call for help on social media. Some two hundred Natives from Minneapolis and nearby reservations had assembled in the parking lot of a coffee shop called Pow Wow Grounds, which became their makeshift headquarters over the next week. The man with the shotgun and his compatriots were Ho-Chunks from a reservation on the Mississippi River, about an hour south of the city.

They were adhering to a principle that AIM had helped establish fifty years ago: given that law enforcement was complicit in their oppression, oppressed communities must protect themselves. On the surface, such armed neighborhood patrols appear fairly similar to vigilante groups like the Oath Keepers or the various militias in Michigan and elsewhere. A crucial difference, however, lies in the legitimacy of their respective grievances.

In 2014, Cliven Bundy, an elderly rancher in Nevada, declared war against the government when the Bureau of Land Management impounded his cattle over his refusal to pay outstanding razing fees. Hundreds of Oath Keepers and other right-wingers rallied to his cause, surrounding law enforcement agents and training rifles on them until the government released the livestock and withdrew from the area. A year later, Bundy’s sons, Ryan and Ammon, fomented opposition to a federal arson case against fellow ranchers in Oregon; dozens of armed right-wingers again answered the call, seizing the headquarters of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge.

In many respects, the Bundy-led standoffs were a ham-fisted imitation of the 1973 occupation by AIM activists of Wounded Knee in South Dakota. In 1890, the US Army had massacred hundreds of Sioux men, women, and children at Wounded Knee, clearing the way for the acquisition of their homeland. Like contemporary proponents of that crime, the Bundys believed that God had entrusted them with proprietorship of the physical United States. The Malheur Refuge originally belonged to the Paiute people; during their occupation, the Bundys and their supporters excavated a road through sacred Paiute burial grounds and released a video of themselves rifling through Paiute artifacts. At the confrontation in Nevada, Cliven Bundy had often cited his settler ancestors to support his claim of sovereignty over the vast public desert where he illegally grazed his cattle. But ancient sandstone petroglyphs attested to the Paiute who’d lived there long before any Bundys came.

Some of the Sioux who were slaughtered at Wounded Knee in 1890 had already been confined to a reservation, which they had fled two weeks earlier, after Indian police gunned down their leader, Sitting Bull. That reservation was called Standing Rock, and in 2016—the same year that the Bundys occupied the Malheur refuge—it became the site of another standoff. When an energy company undertook to install a pipeline that would traverse the Mississippi River half a mile upstream from Standing Rock, in an area that Sioux still claimed as rightfully theirs, Indigenous activists attempted to impede its construction. People like the Bundys and their allies would like to conflate their actions with those of such Native activists, but in fact they are intrinsic to the system that that the latter oppose.

The irony of this dynamic was on full display on July 3, 2020, when Trump rallied his supporters against racial-justice protesters in a speech that he delivered at Mt. Rushmore. The Black Hills of South Dakota, or Pahá Sápa, are a sacred homeland for the Sioux, whose ancestors called them “the heart of everything that is.” In 1868, the US signed a treaty guaranteeing the Sioux “absolute and undisturbed dominion” over the area. Then gold was discovered there, and a quarter century later the government put a grisly end to Sioux resistance at Standing Rock and Wounded Knee. During his speech, Trump did not mention the Sioux. Instead, he portrayed white Christians as victims of “far-left fascism.” Citing the same divine entitlement as the Bundys, he then characterized the very possibility of justice or restitution for historically persecuted communities as a threat of dispossession: “That which God has given us we will allow no one to take away.”

LH: How far has the far right gone in co-opting the language of civil rights?

LM: The first anti-lockdown rally that I attended was held in Grand Rapids, at a plaza known as Rosa Parks Circle. The keynote speaker was Dar Leaf, a sheriff from nearby Barry County who had refused to enforce the governor’s COVID-related executive orders. Taking the mic, Leaf invited his (entirely white) audience to imagine an alternate version of the past—one in which Alabama officers, upholding the Constitution, had not arrested Rosa Parks.

To facilitate the thought experiment, Leaf channeled a hypothetical deputy boarding the bus on which Parks—in the real world—was detained. “Hey, Ms. Parks,” said the sheriff, playing the part. “I’m gonna make sure nobody bothers you, and you can sit wherever you want.”

The crowd cheered.

“Thank you!” a white man called out.

In Alabama, during the 60s, sheriffs and deputies were often more ruthless than their municipal counterparts toward Black citizens. But Leaf saw himself as heir to a different legacy. According to him, the weaponization of law enforcement to suppress Black activism arose from the same infidelity to American principles of individual freedom that in our time defines the political left. “I got news for you,” Leaf said. “Rosa Parks was a rebel.”

Leaf belonged to the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, which was founded by the former Arizona sheriff Richard Mack. Mack had joined the Bundys during their standoff in Nevada. After the Bundys defeated the Bureau of Land Management, he’d told reporters, “This was Rosa Parks refusing to get to the back of the bus.”

What has been striking to me is how sincerely many Americans on the right believe that such equivalence is accurate and justified—how profoundly oppressed they really feel. They’re not just co-opting the language of civil rights. They are living the emotional experience of victimhood. The frenzied mob violence of January 6 revealed how intoxicating this experience can be (especially when it is untethered from reality and can be indulged in without the psychically taxing pressures of actual oppression).

I fear that this basic appeal will continue to draw people to the nativist conspiracy theories and movements that populate the world with phantom threats to white Christians. Earlier this year, I attended an anti-vax rally on the National Mall where thousands of citizens from around the country, including Proud Boys and members of other groups that had attacked the Capitol, listened to speakers on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial compare themselves and their cause to Marin Luther King and the civil rights movement. “Every capitulation is a signal to the oppressors to impose new forms of torment and torture,” the keynote speaker, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., warned.

“There’s only one way,” an older man standing beside me told his female companion, who nodded in agreement. “You think they’re gonna be voted out? Give me a break.”

___________________________

Luke Mogelson’s The Storm is Here: An American Crucible, is available tomorrow from Penguin Press.

Luke Mogelson

Luke Mogelson is the author of The Storm is Here: An American Crucible, out now from Penguin Press. He has written for The New Yorker since 2013, covering the wars in Afghanistan, Syria, Ukraine, and Iraq. During the pandemic, he reported from across the US. Previously, Mogelson was a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine, based in Kabul. He has won two National Magazine Awards and two George Polk Awards. His short story collection These Heroic, Happy Dead was published in 2017.