__________________________________

This isn’t anyone’s autobiography. What I’ve lost is so easy to name as to make it impossible to speak about.

These are the two terse sentences Clare Elwil has been writing for the past ten weeks. Her notebook jitters on the tray table. Even a single additional three-word phrase would be an improvement. For ten minus three is seven, which is equivalent to three plus four, and three times four equals twelve, which, one plus two equals three, again. Ten divided by three is a little more than three. Ten times three is thirty, and three plus zero is three. The plane, meanwhile, is one. It’s grievously small. Clare is on the plane. It was impossible to fly direct and that of course indicates something about where she is going. It was a good day this morning, light and bright; yet, occasionally, as the plane darts and veers on its descent down the unpleasant roads of the midwestern sky, she fears loss of consciousness. For a few months now her distress has attached itself to back-ground noise; it is no longer “in” her. It arrives. “On catlike feet.” This is someone’s poem, no doubt? A book on the piano in that apartment. Her mother’s apartment, Clare corrects herself. She is headed to the Seminars.

Slumbering beside her is a very pink man in his late fifties. His oblivion gives Clare ample opportunity, if not permission, to study the boyish short-sleeve button-down shirt he must wear in acquiescence to some regional career norm. Gray hairs curl on his speckled arms. His face has collapsed under weight of dream. He sighs. He is a machine for living, simple in conception and construction. In the right breast pocket of his button-down his boarding pass is displayed, as if to signal a belief that it might be reasonable and acceptable, a sensible business practice, that he be asked to leave the plane midflight should he be unable to produce the document at a moment’s notice. Associated with him is a salty scent, a faint musk; essentially inoffensive.

Clare’s body, specifically her head, rebels. Dread is taking on several recognizable shapes—like continents of the northern hemisphere of the planet Earth or, perhaps, she manages to think, these are sheep. Sheep! They lumber toward her, throbbing electrically. Or hogs. Are there three? It is possible there are three of them. Maybe four: a fourth hides behind the body of one of his fellows, seems briefly to merge stickily with the others—viscous and amorphous—before coming unabsorbed once more. “Pigs,” Clare mutters, as the angle of descent is rendered more pronounced by the professional whose gestures control this can.

Clare is a year late. She should have been making this bizarrely perilous short flight, like being thrown across the state of Illinois, at the end of the summer of 2002, when she was still a great writer. Admittedly, she had been a very young great writer, but all magnificently accomplished persons have had to be something before the period of universally acknowledged dominance—and Clare was evidently, tellingly being what she was then, which was very, very promising. It is in description now that Clare has a tendency to become most mired. No, now it is in description that Clare has a tendency to become the most mired. The tendency? Is that the word? Mired?The? She slides back and forth, on wheels, mobile yet unable to pass over the hump that stands between her and poised, proper articulation. What was it she was? Who was there? The very sentence is unnatural. The sentence is very unnatural. Who? Had anyone in fact said or believed this of her? The sense that this had happened somewhere, the naming of her, the praise of her, the walking to the home of the doughty publisher, the short man, his cobbled streets. She was to receive the award before a polished black piano. His piano, not her mother’s. To someone, oh someone, then one Clare Elwil, these events had occurred. “You have a name for a book cover,” an anemic woman in a pair of avant-garde earrings, nests of silver thread, had whispered. Clare was a stylist, a judicious narrator. She sold her story to the room. She was someone, the worthies said, who should be driving the bus, and there were daffodils jangling everywhere in Cambridge.

Here, the plane touches earth. Clare gags. A black star blooms, and she maintains herself in a kind of (obviously wishful) corporeal stillness, by force of will. The pink man stirs.

The plane bounces. There comes a smattering of applause.

Clare Elwil is in the middle of nowhere, where she will remain for the next two years, and what no one knows but they will soon discover is that she can no longer write.

__________________________________

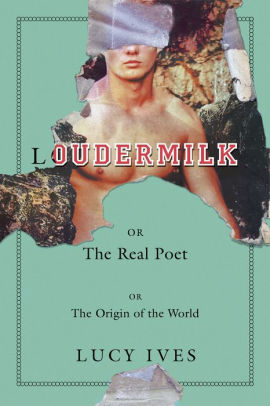

Excerpted from Loudermilk: Or, The Real Poet; Or, The Origin of the World with permission from Soft Skull Press. Copyright © 2019 by Lucy Ives.