After a few minutes, the rigidity of the black and white photos would, if not depart, then liquify. A day’s immersion left the same mental after-dazzle as a sun-glanced afternoon, lakeside.

These non-existent beams, hurled up from non-existent tree-fringed and flickering bodies of water, were the perfectly normal sensational offshoots of gazing at photos all day. They were access to, glimpses of, Arcadia: The Grand Ahistorical Mythical Paradise which is the ultimate project of all Arcadian Personality Types who crave a paradise knit out of visions of the past much like their more illustrious cousins, Utopians, do with the future. (It—paradise—is ultimately to be a collaboration.)

Utopian Personality Types, as a rule, find old things redolent of decay, and can just about put up with new things which are still not the future.

The classic counterpart traits of the Arcadian, like a fondness for old objects and buildings, and an inclination towards historicised figments, were, as far as I was concerned, much easier to inhabit for white people, who continued to cast and curate all the readymade, ready-to-hand visions. Being born in a body that’s apparently historically impermissible, however, only meant I was not as prone to those traps that lie in wait for Arcadians—the various and insidious forms of history-worship and past-lust. I would not get thrown off track: I could rove over the past and seek out that lost detail to contribute to the great constitution: exhume a dead beautiful feeling, discover a wisp of radical attitude pickled since antiquity, revive revolutionary but lustrous sensibilities long perished.

Not prone but certainly not impervious.

The photographs we had been sorting through had thus far consisted mainly of holiday shots. Some quite spectacular. Europe in the ’20s and ’30s. Old pensiones and hotels. Scenes of a modernist Alpine Queerdom.

The photographer, I thought, must have been the short dark-haired man who occasionally came in and out of shot, but it was hard to say, as there was also a gloriously imperious woman that might have been his wife (which did not seem to stop either of them partaking in the Alpine Queerdom).

These photos had so far yielded two images of Stephen Tennant. One was a mountain scene in Bavaria, the other on a bright, empty beach, hand in hand with a doting Siegfried Sassoon. I had to lie down on the floor. Neither Elizabeth/Joan nor Agnes commented, for which I was grateful.

Today we had finished taking notes and ordering the first box of many, now ready for the next department where it would be sorted through all over again to verify our identified sitters and dates whilst looking for any others. This would happen twice more before they were all digitised.

There was a definite elation slicing open the next box, which Agnes did ceremoniously, putting on tweed gloves and using her mother-of-pearl nail scissors since, along with most of the equipment, the Stanley knife hadn’t arrived.

This series struck upon a different channel. Less bucolic sightseeing and more cosmopolitan. Pictures of Parisian nightclubs, many where the photographer had obviously been intoxicated. Elbows and blurred faces of interwar bohemia. One of what must have been the Revue Nègre where, though it was impossible to see who was on stage, Agnes immediately identified Josephine Baker by a visible scrap of dress. Many showed the London club scene of the ’20s. Places like the original Café de Paris, the Gargoyle Club, Café Royal, the Blue Lantern. It was amongst these we began finding photographs of a particular party.

The party was at a country house I recognised at once as Garsington, home of patron and hostess Ottoline Morrell. It was a particularly animated looking soirée. Different to the usual pictures of Garsington parties I’d seen with members of the Bloomsbury Group lying about sedately in deck chairs chatting, bitching, smoking. Some of those figures were there—I screamed at Agnes when I pulled a picture of Vanessa Bell out of a pile, and then screamed again at one with half of Virginia Woolf in conversation with a whole Duncan Grant.

There was a comparatively loucher crowd at this party than the Bloomsberries; swathes of apparently uninvited guests. Ottoline Morrell herself was in one snapshot, towering above the rest, a tall woman who accentuated her height with heel extensions, looking not only unfazed but delighted by what were probably party crashers; laughing amidst dark, frayed young creatures. Some of the guests were in costume and half-costume and it looked as if they had come to Garsington directly from at least three different parties: a mixture of artists and students and various denominations of the Bright Young People.

My eyes picked out amongst the piles some blue-edged pictures which I knew immediately to be photographs taken by Ottoline Morrell; she’d always had these mounted on grainy blue cards and I’d seen many of her thousands of photographs held at the archives, but those before me had probably not been seen for decades.

They were pictures of the same party. Unlike the photographs we had been going through, Ottoline annotated all of hers with names on the paper border. In one was the dark-headed, wicked elf of a man with the marvellously arrogant woman and some other people. It was the first where I had seen the man and woman in the same shot. Written below was,

Hugh and Florence St. Clair,

and on the back,

To Florence, You said you should like a photograph, please send me one of your own. Ottoline.

Which meant they could have been married, but looking at them it was obvious they were siblings. I was about to call out to Agnes that I had found the name of the photographer but there was another blue-lined image. Also at Garsington. A room panelled much like the one I was in. A young man and two women in elaborate costume as Late Renaissance angels. Arched wings impressively constructed of wax and what must have been peacock feathers. All three posed in a befittingly exaggerated Mannerist style, as if each occupied the panel of a triptych. The two on either side flaunted heraldic robes, whilst the central woman wore emblazoned pieces of armour over a fine mesh of chainmail. She had on a coronet, around which her hair was brushed into a commanding nimbus.

Beyond photographs taken for colonial documentation, I wasn’t sure if I’d ever seen a photograph of a Black person from this era, with hair this texture, that hadn’t been ironed or lye-straightened. Certainly never in such a setting. An excruciation of coil and kink, for it made me ache with jealousy and bliss. In a chain-mailed hand she clutched a champagne coupe like a holy grail. The other palm was angled just a bit away from the lens, fingers arranged in an obscure saintly message, but at the same time holding a cigarette. I was about to call out to Agnes again, but instead found my hand with the photo in it slipping under the table towards my coat pocket.

There was a second picture of the same trio. They’d changed position, all looking less mannerist but giving an excellent profile.

When I finally called Agnes over,

“Oh, that’s your Mr. Tennant is it not?”

And yes, it was. I hadn’t even noticed. The young man to the left was Rex Whistler, which I had already vaguely registered, but the other angel on the right, the second young woman, was of course Stephen Tennant.

“But who’s the young lady in the middle, a singer?”

“No.”

Even for Agnes it was the obvious suggestion: a Black woman at a bohemian party in England in the ’20s was not unlikely a singer like Florence Mills, or Josephine Baker, who were sometimes invited to such events as entertainment and also sometimes as guests. But I thought not, without knowing why.

“What does the name say?”

Another thing I hadn’t noticed.

Steenie, Hermia and Rex

Steenie was a nickname for Stephen. But on reading the name Hermia, another rose up in response: “Druitt.” I was absolutely sure of it. Hermia Druitt. My mouth ached to say the name aloud.

“Hermia Druitt.”

__________________________________

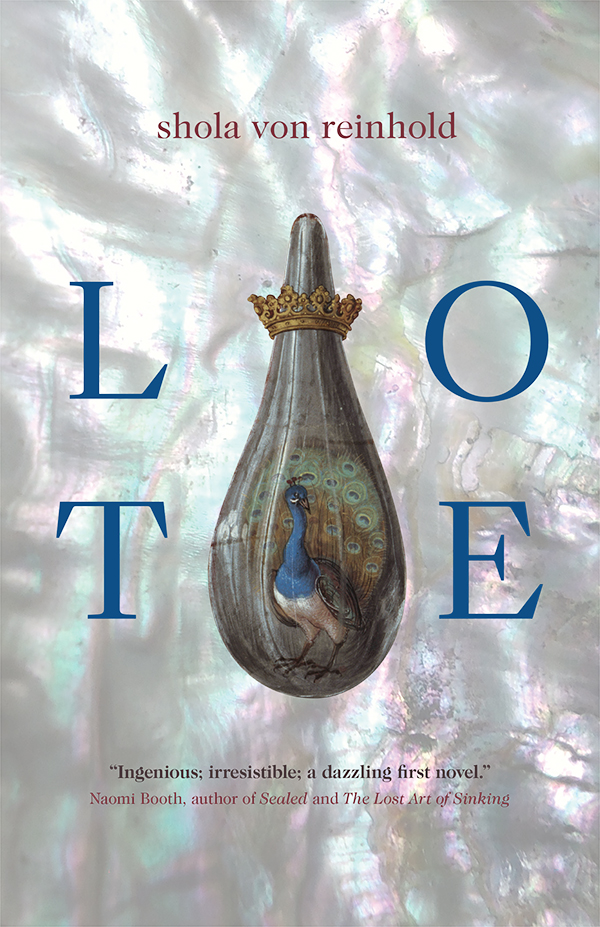

Excerpt from LOTE by Shola von Reinhold (Duke University Press, 2022), available in Canada from Metonymy Press.