Looking at the Other in the Midst of War

Sarah Sentilles on Empathy, Art, and Abu Ghraib

Two students were in the classroom when I arrived early to rearrange the chairs, from rows to a semicircle, so we could have a discussion.

One elbowed the other. Tell her, she said. Miles shook his head.

Tell her.

He shook his head again.

If you don’t tell her, I will, she said.

Fine, he said. Tell her.

Miles was a soldier in Iraq, she said. He was stationed at Abu Ghraib.

*

It felt like a movie, people said, watching the planes hit the towers, watching the towers fall.

*

Miles replaced the soldiers who replaced the soldiers in the photographs.

Both students were art majors taking my critical theory course, and the woman told me what Miles was painting: images of the children who were kept as prisoners in Abu Ghraib.

There were children? I asked.

Miles used his nephew as a model, dressed him up in one of the yellow jumpsuits he brought home from Iraq. He photographed his nephew wearing the jumpsuit, then painted from the photographs.

I didn’t know what to say. For years I’d been researching Abu Ghraib, writing about those photographs.

Students were filling the room. Class would start in three minutes.

If you ever want to talk about what you experienced there, I said to Miles, I’d be happy to listen.

*

Artists set up listening stations in the days after September 11 on the streets of New York City, on subway platforms, in train stations. Would you like me to listen to you? they asked people walking by, and people stopped to talk. Reflective listening, simply repeating what someone says to you, is supposed to be healing.

Ever since that day I feel alone.

You feel alone. Tell me about your loneliness.

I feel alone when I’m with people, even my own family.

You feel alone even when you’re with people, even your own family.

Yes. I am afraid.

You are afraid.

*

When class ended and I was gathering my things, Miles walked up to me. Can we talk now? I remember him asking.

*

They call the secret prisons outside the United States black sites. They call the detainees whose names they don’t record ghosts. They call torture techniques that leave no physical marks clean.

In Torture and Democracy, Darius Rejali explained how governments that torture have to develop clean techniques to evade detection by the groups monitoring them—the Red Cross, the United Nations, Amnesty International, the ACLU. Interrogation teams are trained in methods that leave no marks. Stealth torture. Allegations of torture are simply less credible when there is nothing to show for it.

Stealth torturers use what’s easy to find—sheets, gas masks, police batons, light bulbs, buckets, cardboard boxes, water, ice, blankets, hoses—because if anyone were to come looking for torture devices, they wouldn’t see any. You can hide a blanket and a cardboard box in plain sight. You can let ice melt.

Stealth torture is not new. American slavers created ways to torture the enslaved that would leave no mark because they knew any future buyer would think that bodies with scars must be trouble—and would not purchase them.

*

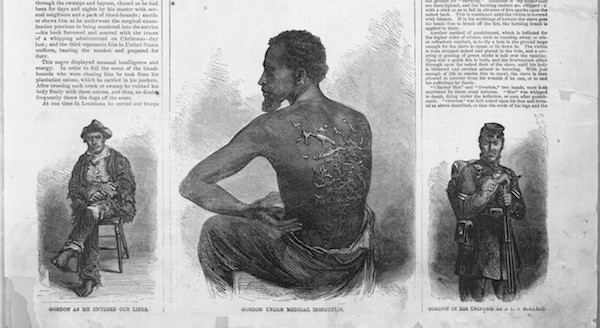

The Scourged Back is a photograph of an enslaved man named Gordon, his back scarred by a severe beating, the lashes from the whip visible in raised lines. In 1863, Gordon escaped slavery, fleeing toward the Mississippi River with onions in his pockets, which he rubbed on his skin to avoid detection from the bloodhounds his owner sent after him. It was during the Civil War, and when Gordon reached Union soldiers in Baton Rouge, he declared he wanted to join the Union army. Doctors examined him and discovered his scarred back. They asked the camp photographers to take Gordon’s picture. The portrait of Gordon—shirtless, his head turned to the side, the scars so raised they catch the light—was mass-produced and circulated around the country. A writer for the New York Independent wrote, This card-photograph should be multiplied by the hundred thousand, and scattered over the States. It tells the story . . . to the eye.

*

Miles and I sat together in my office, which was not really my office. I shared it with several other part-time adjunct professors. The desk coated with dust, the keyboard filled with it, nothing on the walls.

He started to talk.

*

Miles lived in a cell in a bombed-out prison; all the soldiers did. A hole blown through the wall allowed the wind to come through.

They’d been helicoptered into the prison complex and could bring stuff for only two to three days because they had to keep the weight down for the flight. One soldier didn’t follow directions, and her bag was too heavy for her to carry. Miles had to decide what would be safer: for him to carry her bag or for the woman to carry it and slow everyone down because they couldn’t run around her, because the slowest person always set the pace, and if they were moving slowly, people could shoot at them, because the walls around the complex were so low you could see right over them, and on the other side of the wall was one of the most dangerous roads in Iraq, and people shelled the prison from that road all the time. They had to move quickly.

Miles traded bags with her.

It was freezing in the prison that first night, and Miles had no blankets. In his cell there was no bed frame, no mattress. He found a mattress in another part of the prison. He put it on the floor of his cell and covered himself with magazines and his duffel bag to try to keep warm.

*

An 18-year ban on publishing photographs of flag-draped coffins of US soldiers was lifted by Barack Obama in 2009. In Soul Repair, Rita Nakashima Brock and Gabriella Lettini argued the media blackout hid the costs and consequences of war from public consciousness. We choose collective amnesia about war and its aftermath, they wrote. Veterans return to a nation unwilling or unable to accept responsibility for sending them to war.

*

What surprised Miles most about war was the intimacy. He hadn’t known how much touch there would be, how much physical contact. His first job at the prison was to supervise scanning the eyes and fingerprints of new arrivals. Soldiers stood next to detainees, side by side, shoulders touching. They’d position palms on scanners, press fingers on the glass. It was like they were holding hands.

*

Pierre Bourdieu wrote that feelings like friendship, love, and sympathy can be transferred between bodies, from one person to another. Bodies acquire the same dispositions when they are located in the same place in the social structure. Bourdieu called this synchronized morphology.

*

I heard a story on the radio about a scientist who programmed a computer to repeat back whatever a person typed into it. The hope was to create a cheaper, more accessible form of therapy, the illusion of being listened to. But one of the people who worked with the scientist started coming to the office before anyone else was there, and when the others would arrive, they’d find her talking to it, typing in the story of her life, waiting for the computer to answer her. She told the computer everything.

I miss my father, she typed.

You miss your father.

I love you.

I love you.

No one knows me like you do.

No one knows you like I do.

No one else listens to me.

I’m the only one who listens.

*

Miles was supposed to be a cook—that was what they’d trained him to do, prepare food, assemble meals for soldiers to eat—but that work was outsourced to private corporations, so they made him a guard at the prison instead.

He drank his coffee in the medical tent every morning in Iraq and watched the detainees get shots—vaccines for tetanus, measles, mumps, rubella. Most of the prisoners were scared, they didn’t understand what the shots were for, and sometimes Miles smiled at them to try to make them feel comfortable, and sometimes they smiled back, and sometimes he teased them, told them the shots were poison, put his hands around his throat like he was choking, like he couldn’t breathe. Some of the prisoners were so afraid of the needles that they’d pass out, and everyone in the medical tent, including the other prisoners standing in line, would laugh.

*

Some governments build elaborate torture chambers. The House of Fun was designed by a British firm that advertised the setup as prisoner disorientation equipment. Installed in Dubai Special Branch Headquarters, it was outfitted with strobe lights and white-noise machines and took on the appearance of a disco, but the sound that could be generated inside that space was so loud it was capable of reducing the victim to submission within half an hour.

*

Miles told me he didn’t decide to go to war because he supported the war. He didn’t think there were weapons of mass destruction. He went to war because he wanted to go to college, and joining the military seemed like the best way to pay for it. And that was true for most of the soldiers he knew. Their reasons were pragmatic, and once they found themselves in-theater, they did their jobs and they did them well, because if they didn’t, they’d die or their friends would die or the people next to them would die, and the war became about protecting each other, about being willing to die for one another. When you’re there, he said, all you want to do is protect your buddies.

*

Miles told me I was the first person who’d asked about his experience in Iraq. He’d been back for more than two years.

*

Flying home after visiting my parents, I heard the captain announce there was a soldier on board. Then I watched everyone who passed the soldier on the way to or from the restrooms at the back of the plane touch his shoulder or call him son or thank him for his service. One passenger, an older man, stopped at his row and hit the button above the soldier’s seat so it lit up. A drink, he said. Anything you want. And the flight attendant arrived and offered the soldier a tray of tiny bottles to sift through, the sound of the glass like marbles. The man stood in the aisle next to him, talking while the soldier drank his bourbon and Coke, telling his stories about war, about Korea.

When the plane hit the runway, the captain spoke again, directed the passengers to stay seated when we reached the gate, to stay seated even when the seatbelt light turned off, to let the soldier off first. The least we can do, he said. Show a little appreciation for our men and women in uniform.

Applause followed the soldier down the aisle.

*

Most civilian actions toward veterans shield us from accepting our own complicity in war, Brock and Lettini wrote.

*

The barred walls of every soldier’s cell were covered with plywood to make them more private, Miles told me, though the plywood didn’t reach the ceiling, so you could see the light in the cells next to yours and you could hear one another. All the windows were blacked out with paint. Otherwise snipers would be able to see right into the prison and kill you.

Miles was friends with the guy in charge of supplies, so he was able to get Sharpies, even a good set of thicker felt markers. He drew images all over the plywood walls of his room—Spider-Man, Batman, characters from The Simpsons, his friends, other soldiers. On the door to his cell he drew his own name, made it beautiful.

When his tour was over, people told him to take the walls with him, that he’d want his drawings when he got home, but he couldn’t imagine ever wanting any of it.

He wants it now.

*

Fayum portraits—images created thousands of years ago in beeswax and pigment on wood or linen in a town called Fayum, south of Cairo—were painted while the subject was alive, but when he or she died, the image was attached to the mummy and buried. The images ensured safe passage through the underworld. They worked like passport photos, identifying the person’s body on his or her journey.

Fayum portraits were images destined to disappear. What does it mean to create a painting the artist knows will exist only with the dead, in the dark?

I’ve always been taught the job of the artist is to look, but in The Shape of a Pocket, John Berger insisted the Fayum artist had a different job—not to look but to be looked at. The artist paints being looked at, he wrote. This is the contract between artist and subject, and it is an intimate one. The two of them, living at that moment, collaborated in a preparation for death. The subject addresses the artist, speaks to her in the second person singular—you—and the artist’s reply, which is the painting itself, uses the same intimate voice: You, the one who is here. You, who will very soon, too soon, not be here.

*

Miles’s assignment was changed from fingerprinting new detainees to guarding prisoners in the yard outside the building. They were kept in cages, larger versions of what you might find at a kennel for dogs. The prisoners prayed five times a day on mats they were given, their voices beautiful. They knelt on the ground in rows, and the guards would be quiet while they prayed, and the prisoners returned the favor by being silent on Christmas. It was a sign of respect, Miles told me.

In some of the cages were children, in others old men. Many spoke English and Miles became friendly with them, joked with them to pass the time.

*

Inta, the Arabic word for you. That’s what the soldiers called every prisoner, Miles said.

The soldiers who worked the yard kept their cigarette butts in a jar. Hey, inta, one of the soldiers said to a prisoner one afternoon. Guess how many cigarette butts are in the jar.

If he didn’t get it right, he’d have to spend two hours in the cage reserved for prisoners who were in trouble.

A few soldiers brought the jar to that prisoner and made him write down his guess, made him dump out all the butts, made him line them up in neat rows in the dirt, made him count each one.

So many things were funny there that aren’t funny here, Miles said.

*

Consider this sentence, James Elkins suggested: The observer looks at the object. It seems simple, even obvious, a given, but the sentence comes apart right away, because it’s built on the mistaken idea that the observer and the object are two different things. The beholder looks at the object, but the object changes the beholder, and therefore the beholder does not look at the object.

Or consider this sentence: The soldier kills the enemy. It sounds like a one-way gesture, but it’s not, because the act of killing doesn’t only change the person who is killed. The act of killing changes the killer, Elkins wrote.

In The Body in Pain, Elaine Scarry put it differently. Every weapon, she wrote, has two ends.

*

Calling other human beings inta, calling other human beings you instead of addressing them by name, dehumanizes, creates distance between guards and detainees, but what if it had been Berger’s you, the Fayum you, a way of saying to the people they were charged with watching, to the people who were watching them: Both of us are destined for the dark.

__________________________________

From Draw Your Weapons. Used with permission of Random House. Copyright © 2017 by Sarah Sentilles.