Have you ever heard about Koschei the Deathless? Koschei is a villain, in possession of many treasures that he hoards. He may not be killed unless someone breaks the needle that is his death. That’s way more convenient than having a lousy heel, like Achilles, or vulnerable locks, like Samson. And it’s better than being mortal. You take the death needle, and you store it in a place where no one can find it. Then you live forever, or as long as you want to live. In the fairy tale, the needle is concealed within an egg. The egg is within a duck, the duck is within a hare, and the hare is inside a chest suspended on a branch on a tree growing on a cliff that overlooks the stormy sea.

So what does this have to do with a skinny young boy who packs lipsticks into a jar, then puts the jar beneath his shirt so that he can try to get it halfway across the city of Moscow un-detected? It’s 1999, everything is covered in asphalt, and while it may seem too late for any folklore myth to be unfolding, in Russia fairy tales predetermine reality. The boy’s name is Mitya and he’s twelve. He has a needle somewhere deep inside his body, which he believes makes him invincible. His dreams are full of sticky, viscous fairy tales, where he is Koschei. But there’s no resolution yet, whether he’s the villain or the hero. Perhaps Mitya should decide, but he doesn’t like making decisions. He can’t even decide if he’s a boy or a girl.

This is why he has the jar of lipsticks. And many more jars, in fact: his treasures, some with colorful clothes inside them, some with other kinds of makeup. And he’s taken them from the pre-revolutionary apartment building on the Old Arbat street, where he grew up, and where there were many convenient nooks to hide things, to a new apartment in one of the superblocks in the residential area called Chertanovo in the south of Moscow. It’s a much smaller space, and Mitya is still figuring out how to store these jars in a way that his parents won’t discover them.

Mitya has had some fascinating events occur in his life lately. He almost solved a murder, almost committed another murder, almost moved to a new country.

At one point in school, they studied fractions, and Mitya had a tough time understanding that halves are just that, halves, 0.5, 50%, ½. What if one of them is bigger than the other? Mitya is not good at math, as you can see. But he’s good at imagination. Mitya is utterly convinced that no one has ever looked at two halves long enough, or attentively enough.

Now that his family is moving—because his parents have lost a lot of money in the recession and had to sell the apartment—Mitya is secretly excited. He knows that the other half of his life is starting and that it’s going to be better than the previous one. Besides, he’s going to be thirteen soon. Everyone is always so dismissive of the number thirteen, giving it a bad name, that Mitya knows for sure: the overlooked number is bitter. Recognize it, and it will make you happy. So Mitya thinks that at thirteen he will be the happiest. After all, why shouldn’t he be? He’s moving and leaving some nasty things behind. Like his cousin, Vovka. Terrible Vovka. Mitya’s father, Dmitriy Fyodorovich, who is also Vovka’s uncle, says that Vovka is staying behind so he can rot. Mitya silently agrees with his father, which doesn’t happen often. It also makes him sad that the better half of Vovka’s life is behind him.

This is where it’s about time to start wondering: How does an almost-thirteen-year-old boy live with a needle inside of his body? Shouldn’t he see a doctor? How did the needle get there in the first place? Well, this is a long story, which needs to be told from the beginning. It’s hard to say whether anything exciting would happen to Mitya at all, if not for the incident with the needle. Maybe Mitya would not be hiding lipsticks in a jar beneath his T-shirt now. So listen to the tale closely, and don’t interrupt. Whoever interrupts will have a snake crawl down their throat and will not live longer than three days from now.

***

It all began when the Soviet Union was still united, which was, by the accounts of everyone around Mitya, a much better time. He couldn’t know for sure because the events surrounding the USSR’s collapse were about as dim as anything that happens in one’s childhood. So Mitya was forced to trust the words of adults until he knew better. Mitya’s grandmother, Alyssa Vital-yevna, liked retelling the events that occurred one night when Mitya was two years old, which made Mitya believe that what happened that night was a fateful, life-altering accident.

According to Alyssa Vitalyevna, Mitya was weak and frail as a toddler but had the stamina of a scavenger bird when it came to picking up small objects that had fallen on the floor, or even on the ground outside. His mother, Yelena Viktorovna, once had to pry a morsel of moldy bread from his tightly shut mouth. She then escorted Mitya off the playground as the other mothers, not even trying to conceal their voices, declared, “That Mowgli.”

Yelena Viktorovna and Mitya never returned to that playground. “These other mothers aren’t worth the soles on my shoes,” Yelena Viktorovna hissed. She was of an utmost conviction that she, the daughter of a distinguished space scientist and a graduate of the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, was far superior to the other women.

After that, she did not let Mitya out of his stroller on walks. He was allowed to go on slides and swings only when escorted by his father, Dmitriy Fyodorovich. After all, Dmitriy Fyodorovich was an Afghan War veteran, and his army brand of discipline was reliable in preventing any mishap.

That one evening, Mitya’s parents went out to dinner at the home of their colleagues from the Rubin factory. Dmitriy Fyodor-ovich made televisions at Rubin, and Yelena Viktorovna provided bookkeeping services. The colleagues lived in a room in faraway Medvedkovo, and so his parents left Mitya with Babushka, who lived with them in the apartment. Nothing could go wrong.

Alyssa Vitalyevna, who was, by the way, a fourth-generation Muscovite, did not consider herself a natural-born caretaker. She didn’t mind looking after Mitya, of course: he was a lovely, docile child with eyes like blue buttons and blond curls. Most importantly, he looked nothing like his father, whom Alyssa Vitalyevna loathed. She went to great lengths to avoid addressing Dmitriy Fyodorovich in the second person and referred to him as “indyuk,” turkey cock, or “armeysky sapog,” army boot.

Alyssa Vitalyevna was not that kind of Russian grandmother who dedicates herself to baking pies and knitting socks for the grandchildren. She had better things to do than babysit. She had phone calls to make; she had stitch patterns to finish and, maybe, to gift. She had a boyfriend, the Greek Dr. Khristofor Khristofor-ovich Kherentzis, who would not survive without her guidance and instruction.

Reluctantly, Alyssa Vitalyevna joined Mitya in the living room, which doubled as his bedroom. The Communist Party had given the apartment to Alyssa Vitalyevna’s recently deceased husband, Mitya’s grandfather. He was one of the scientists who invented the first space toilet for the Soyuz spacecraft: a suction cup and a tube for urinating, a small bucket for defecating, all connected to a vacuum pump. “I am the woman who made cosmonauts stop shitting into diapers,” Babushka said when she felt that life was treating her unfairly. It was her utmost conviction that without being inspired by her, Dedushka and his colleagues would never have been able to invent the space toilet. She kept a prototype of the device in her credenza and sometimes took it out. Alyssa Vitalyevna always mentioned how she was a crucial part of the prototyping process—and Mitya never dared ask what this implied, afraid it might have been something intimate, like her trying out the toilet before the cosmonauts.

Alyssa Vitalyevna, regal and flushed with menopause, sat on Mitya’s mustard-yellow sofa that evening wearing a red mohair beret that she never took off in the colder months for fear of drafts. Behind her was a rug tapestry depicting Peresvet, a Russian monk, fighting Tatar warrior Chelubey. Beneath her was another rug, a Middle Eastern red-and-black pattern of crows’ feet and geometric flower shapes. Mitya was crawling on it, trying to find something to put in his mouth. There was nothing but crumbs. He licked them off the carpet and tasted kurabie biscuits and three-kopeck bread rolls with a touch of wet dog.

Alyssa Vitalyevna paid her grandson no mind. She was working on an embroidery: Dr. Khristofor Khristoforovich Kherentzis’s initials on an off-white handkerchief. She was also talking on the phone to her best friend and occasional nemesis, Cleopatra. The TV in front of her was on, at full volume, and both ladies were discussing the events of Santa Barbara, an American soap opera that was all the rage. The main character, C. C. Capwell, a gray-haired millionaire, was splitting from his much younger wife, Gina. In protest, Gina took off her jewelry, got undressed, and left the Capwell mansion naked.

Alyssa Vitalyevna gasped into the receiver. She briefly glanced at Mitya to check if he had seen the impropriety, but the boy was busy studying the rug. Unseen, the needle had detached from the embroidery. And as Alyssa Vitalyevna was shuffling the receiver, she caused the needle to fall off the sofa and onto the rug. Mitya picked up the needle with his little hand. It was thin, shiny, small—Alyssa Vitalyevna was working on the tiniest details, using her most delicate needle.

It was like nothing Mitya had seen before. Maybe if he had stung himself with it, he would have broken down in tears and thrown the needle back on the floor. But it stayed firmly in the boy’s fist. He put the needle into his mouth and swallowed.

Or at least, that’s what Alyssa Vitalyevna figured had happened.

While the end credits were rolling, she realized that something was amiss. She looked at her embroidery, couldn’t find the needle, and gasped. She patted the area on the couch around her, looking. She searched beneath her feet. Then Babushka stood up and explored the area where her buttocks had been. When she couldn’t see the needle there, she bent down and started looking beneath the couch. She moved her open palm across the floor, but all she could find were dust bunnies.

Her attention shifted to Mitya.

“Mitya, did you swallow the needle?” she asked him. And he replied: “Yes, Baba.”

Alyssa Vitalyevna believed that once a person swallowed a needle or even as much as stepped on it, the sharp little piece of steel would immediately get absorbed into the flesh and it would be mere hours before it reached the bloodstream and set on its way to the heart to kill the person. Babushka knew that she had to rush Mitya to the emergency room, but not until she relayed all that to Cleopatra on the other end of the phone line.

Fortunately, it was mid-October, and it was not snowing yet. Alyssa Vitalyevna put on her lambswool coat, grabbed her pocketbook, and rushed down in the elevator with Mitya in tow. As soon as she ran out of the building and stepped into a puddle, Alyssa Vitalyevna realized that she was still wearing her slippers. It was too late to turn back. She ran through the inner courtyard and out into the street. Mitya held on to the front of her cardigan and felt the cold wind brush against his naked calves.

Outside, Alyssa Vitalyevna stopped a car by jumping in front of it.

“Quickly, or the child will perish,” she shouted at the driver, a middle-aged Georgian man in a cat fur hat, as she got into the passenger seat. The man had no option but to obey. Babushka had quite a commanding presence. She propped Mitya against the front panel and gave out instructions on how to get to the hospital. It was about thirty minutes away, on Leninskiy Prospect.

When they reached the hospital, a converted pre-Soviet mansion, Alyssa Vitalyevna barely waited for the car to stop. She jumped out and rushed Mitya to the entrance. The driver shouted his phone number after them. His name was Vakhtang. He must have liked Alyssa Vitalyevna, she later surmised.

The receptionist told Alyssa Vitalyevna and Mitya to wait in line to be helped. The waiting room was full of adults who did not look sick enough to be tended to earlier than Mitya. There were no empty spaces on the benches upholstered in cheap brown pleather along the walls. A wailing preschooler latched on to her mother, who kept shoving a whole peeled onion into her daughter’s mouth. The air smelled of the eternal tug-of-war between urine and chlorine.

Babushka rotated on the barely existent heels of her slippers to face the receptionist once again.

“This child is dying,” she announced.

“You have to wait, zhenshina,” the woman said, oblivious to Alyssa Vitalyevna’s dominating charms.

Babushka had no patience for bureaucracy. She took hold of the phone on the receptionist’s desk and ferociously spun the rotary dial.

“Khristik?” she asked as soon as the call was connected. The usage of a diminutive conveyed the urgency of the situation. “Khristik, dear, Mitya is about to perish, and they will not see him at your hospital!”

Dr. Khristofor Khristoforovich Kherentzis, one of the chief surgeons of the hospital, was not expecting to hear from his be-loved Alyssa that evening. His brother-in-law Zhora was visiting from Sukhumi and mercilessly winning at backgammon.

“Can I maybe put you in touch with my friend Alexei?” he offered.

“But Khristik! You must come right away! I am here alone, and I see no help from anyone!”

Babushka glared at the receptionist.

It was quite pleasant at Khristofor Khristoforovich’s apartment. He and Zhora were halfway through the second bottle, and there was some lamb and ajapsandali left over for a snack later that night. But he also knew that going against Alyssa Vitalyevna’s will could propel him to visit the ER himself.

“I am coming, Alyssa,” Khristofor Khristoforovich sighed. They waited for him in the corner, Alyssa Vitalyevna perched on the windowsill and quite magnificent in her lambswool. Mitya tried to reach the nearby ficus plant and treat himself to its luscious, dust-absorbent foliage, but his arms were too short.

Dr. Khristofor Khristoforovich Kherentzis arrived disheveled in his white undershirt and loosened suspenders beneath his winter coat, smelling like homemade wine. The receptionist immediately began collecting the necessary information to get Mitya’s medical record out of the archive.

“Year of birth?” she asked his grandmother.

“1937,” Alyssa Vitalyevna exclaimed proudly. Now the younger woman had no way of ignoring the importance of her plea.

The receptionist looked at Babushka over her thick-rimmed glasses with a question in her eyes.

“Not you, Alyssa, the boy,” Khristofor Khristoforovich crooned.

“Oh,” Babushka replied. “1986.”

“And the name?”

“Dmitriy Dmitriyevich.” She propped Mitya on her chest. “Last name?” the receptionist asked.

“Noskov,” Alyssa Vitalyevna replied less enthusiastically. She had always disliked Mitya’s last name. Not only did it signify the fact that both her daughter and her grandson belonged to that ridiculous indyuk, but it also came from the word nosok, sock. Whenever she thought of that last name, she could sense the odor of dirty feet in her nose. And the smell, albeit imaginary, had to come from Dmitriy Fyodorovich’s army boots, there could be no doubt about that.

The receptionist retrieved Mitya’s medical record, a thin stack of papers bound in a frivolous floral fabric and filled with illegible doctors’ writing. They were admitted to the X-ray room immediately, and Babushka paraded, proudly, in front of all the ailing patients still waiting in line. She was greeted by the radiologist, an old drinking buddy of Khristofor Khristoforovich. He must have heard about Babushka because he steered away from her cautiously as she entered. He had a bald white head and a red face. Both looked entertaining to Mitya, who tried to lick the doctor’s forehead and then his cheek and compare the taste of the colors. Unfortunately, the doctor never came close enough.

The bald doctor took X-rays of Mitya’s digestive system but found nothing.

“The needle has already reached the bloodstream and could be practically anywhere!” Alyssa Vitalyevna insisted.

“But madam,” the bald doctor started. “It’s not scientifically sound . . .”

Khristofor Khristoforovich gave him a telling glance. It meant that following Babushka’s lead was the top medical priority at the moment.

The doctor proceeded to take X-rays of Mitya’s whole body. Babushka was in awe of how small and neatly arranged the bones inside of him were. The needle was nowhere to be found.

“What a krokhotka,” Alyssa Vitalyevna thought. “And I did not protect him. How small must the coffin be for such a tiny child? And what does one put inside it as a keepsake? A volume of Pushkin’s verse?”

Because the needle remained undetected, the bald doctor let them go. Khristofor Khristoforovich made Babushka promise that she’d carefully observe Mitya’s stool for the needle. If she had the smallest suspicion that he was unwell, she’d call.

She put Mitya on the windowsill in the reception area and hugged Khristofor Khristoforovich in gratitude. Mitya finally managed to get his hands on the ficus plant and ate quite a few leaves off it. Afterward, he had diarrhea. Because of it, observing the excrement inside his potty became both messier and less complicated. Of course, Alyssa Vitalyevna didn’t do it herself. She delegated the ordeal to Yelena Viktorovna, who obediently went through her son’s feces with rubber gloves.

Though the needle was never retrieved, Mitya didn’t die. And so the grown-ups came to the conclusion that it must have gotten stuck somewhere, and would ultimately kill Mitya. Alyssa Vitalyevna realized that she had been complicit in the damage that her only grandson had incurred. She was not religious, but she made a promise to the forces that be. As long as they both remained alive, she would help the boy in everything. As she said these words, she imagined herself, slightly older but as glamorous, pushing the boy in a wheelchair. Passersby stopped in awe, as they noticed the graceful petite woman who so selflessly took care of her infirm son. (He couldn’t be her grandson, could he? Such a young, elegant lady!) Alyssa Vitalyevna was ready for her life to become a sacrifice. She would make it appear effortless. Making sure that the boy would make it in life to the fullest extent of her ability would be her mission.

Meanwhile, Mitya himself did not feel the effects of the needle in his body, or his mind. He was still frail, but comparatively healthy. His limbs grew. He learned to read at four years old, with some assistance from Alyssa Vitalyevna. And in one of the fairy tale books, he discovered Koschei. The coincidence was striking, and it did not take long for Mitya to figure out that the needle was his blessing. It would always shield him from harm and make him special; he was convinced.

It didn’t matter, though. Mitya could talk all he wanted of how the needle was right for him, or of how he couldn’t feel a single symptom: none of it mattered. Mitya was a child, and children, though they quite often possess the clearest, least obstructed view of reality, are never asked to present it.

____________________________________

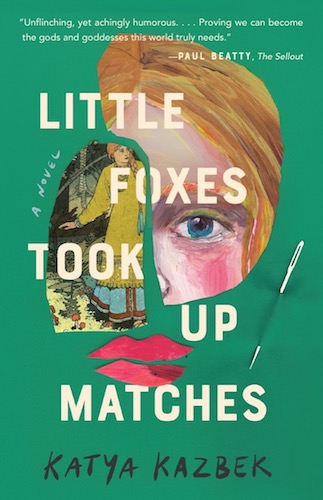

Excerpted from Little Foxes Took Up Matches by Katya Kazbek. Published with permission of Tin House. Copyright (c) 2022 by Katya Kazbek.