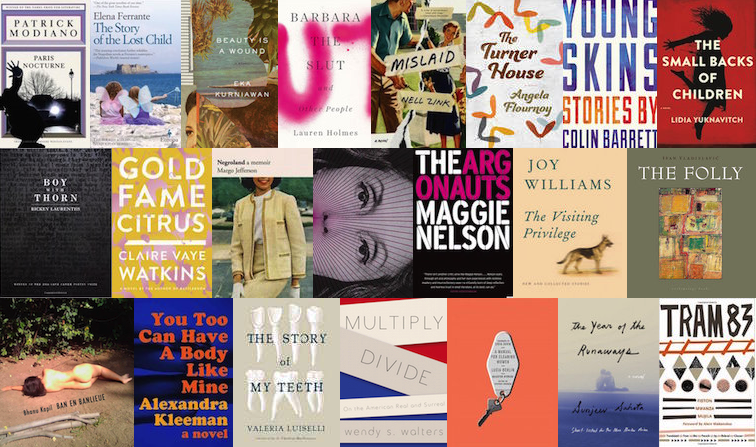

Literary Hub’s Best Books of 2015

If We Had a Staff Shelf, This Would Be It

These are the books we loved this year.

Jess Bergman, Assistant Editor

The Story of the Lost Child, Elena Ferrante (trans. Ann Goldstein): I gave myself over to the Neapolitan Novels this past spring, finally convinced by the one-two punch of Jia Tolentino and Dayna Tortorici’s essays on Ferrante. Not one to approach anything lightly, I became an instant evangelical and converted even my grandmother to Ferrante’s coven. I read The Story of the Lost Child while moving from Philadelphia to New York—a fitting synchronicity, as I expect I’ll miss the company of Elena and Lila, and the streets of Naples, as much as I miss my home city.

The Turner House, Angela Flournoy: As a hate-to-admit-it only child, I have always been fascinated by siblings, and The Turner House artfully sketches no less than 13 of them—plus matriarch, patriarch, grandchildren and a handful of supporting characters. Beyond this character balancing act, Angela Flournoy’s novel is also an impressive work of place, illuminating not only the eponymous house, but also the larger city of Detroit, from the Great Migration through white flight and early gentrification.

You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine, Alexandra Kleeman: You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine foregrounds its intellectual preoccupations without sacrificing feeling—an ideal balance for a reader like me, who loves thinking and crying in equal measure. Kleeman’s grasp of the uncanny is such that I emerged from the end of it feeling disoriented and a little nauseated at the prospect of activities—chewing, swallowing, applying a swipe of eyeliner—that I hadn’t previously thought twice about.

The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson: Maggie Nelson writes the kind of prose that registers physically, a tightening in the chest. Reading The Argonauts defied my usual reading practice of underlining favorite passages; so many lines moved me that it would have felt like defacement to mark them all. Engaging with theory can sometimes feel fruitless and solipsistic, but here Nelson redeems the practice for me, making space in a rarefied conversation for vulnerability, intimacy, and love.

Mislaid, Nell Zink: While I didn’t love Zink’s sophomore effort quite as much as The Wallcreeper (which I mainlined during a single Amtrak ride on my tiny phone screen), I am helpless in the face of her manic energy and relentless zaniness. Full disclosure: My enjoyment of this novel may also have something to do with the fact that in college I belonged to an unofficially co-ed fraternity which bore a striking resemblance to Byrdie’s debauched Thetans.

Blair Beusman, Assistant Editor

The New York Times declared 2015 to be “The Year We Obsessed Over Identity,” and many of my favorite books of the year engaged in this, in terms of content and/or form. Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts interrogates traditional conceptions of normalcy and the nuclear family while blurring the lines between prose, poetry, and theory. Ban en Banlieue, Bhanu Kapil‘s “not a novel,” constantly circles three incidents of horrific racial and sexual violence while refusing to settle into a cohesive form. Valeria Luiselli’s The Story of My Teeth (trans. Christina MacSweeney), written in collaboration with the workers of a Jumex juice factory, questions both ownership and authorship; its culmination features the auctioning of famous works of contemporary art without the artists’ names.

The publication of Clarice Lispector’s Complete Stories (trans. Katrina Dodson) brought English readers 640 pages of her 86 published short stories and a flurry of fawning articles. They are as good as critics would have you believe, and my rabbit is also a huge advocate. Indonesian writer Eka Kurniawan had two novels translated into English for the first time; his epic Beauty is a Wound (trans. Annie Tucker) takes magical realism to *very* dark and depraved places to illuminate the far-ranging impacts of colonialism and warfare.

Emily Firetog, Managing Editor

This year we launched Literary Hub, which meant I was only able to focus on reading (and finishing) short stories or extremely long books/sagas.

Short: Colin Barrett’s Young Skins, which I first read back when I worked with the small Irish press that first put out the collection overseas. Like everyone else on the planet I loved Lucia Berlin’s A Manual For Cleaning Women. Cheers for Lauren Holmes’s Barbara the Slut, which also has one of the best covers this year. And, duh, Joy Williams’s The Visiting Privilege.

Long: I read both of the fourth books of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitian series and Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle (trans. Don Bartlett), although I only finished one of those (Lila forever).

John Freeman, Executive Editor

The Year of Runaways, Sunjeev Sahota: A dozen illegal immigrants living in a house in England are full of stories of love and pain, an overwhelming rebuttal to the notion that there is something less than human in the migrant.

Boy with Thorn, Rickey Laurentiis: Picture a tree on a hill, struck by lightning and set aflame: this book of poems is more beautiful, and more startling.

Paris Nocturne, Patrick Modiano (trans. Phoebe Weston-Evans): In a year full of great short books this is the greatest: a swift existential noir by the master of suggestiveness.

Negroland, Margo Jefferson: A nimble, deft and elegant memoir of a class and a time and a family, and the brilliant writer they made.

Gold Fame Citrus, Claire Vaye Watkins: A smoldering sand-blasted love-story about what happens in California when the water runs out.

Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

The Small Backs of Children, Lidia Yuknavitch: Lidia Yuknavitch is in such command of her language that she can, without fear, let it lead her into places most contemporary writing does not go. She is a writer of great power, prepared to grapple simultaneously with the lofty verities of art and the dark needs of the body, battling her way to a ceasefire with humanity. (TLDR: Houellebecq and Sontag in a fight to the death at the edge of a cliff.)

A Manual for Cleaning Women, Lucia Berlin: Berlin is one of a handful of all-time great American masters of the short story, full stop—and she writes about work. This collection could’ve been called The Lives of the Workers: those who work for redemption or distraction or survival, those who struggle, in jobs and out of them—common tales, yes, but told with uncommon grace and wit. It is painful to finish this collection and realize the writer we so desperately need right now, to keep telling these stories as more and more Americans are forced to live them, actually died 11 years ago.

The Folly, Ivan Vladislavic: Perhaps my favorite book of the year was written in the early 1990s, in a South Africa newly delivered from the multi-generational evil of apartheid. An odd sort of stranger moves into a grown-over vacant lot next door to a nervous, deeply middle-class couple, his intentions unclear… Rare is the dark fable built of such shimmering, perfect sentences.

Tram 83, Fiston Mwanza Mujilia (trans. Roland Glasser): Roland Glasser’s wonderful translation, roiling and musical, delivers Mujila’s profane and teeming portrait of a semi-fictional Congolese city with all the feverish sweep of the modern African gold rush it depicts. Somehow epic, intimate, and morally complex at the same time.

Multiply/Divide, Wendy S. Walters: I would give much to see the world the way Wendy S. Walters does, even for a day, for an hour. The hybridity of this collection—essay cum poem cum fragment cum diary entry—hearkens way back to the continental feuilleton (see: Joseph Roth), a mode of impressionistic observation that can be both broadly political and deeply personal. In Walters supremely talented hands, the one is never far from the other.