By the time the New York Film Festival begins in early fall, most of the big-ticket entries have already debuted—in Cannes, in Venice, in Toronto. But what the Manhattan festival, now in its 60th edition, lacks in buzzy premieres, it makes up for in caliber. Consider the selection culled from aforementioned festivals as a gateway to the year’s finest offerings of international and auteur-driven American cinema, including documentaries, features, and more experimental fare.

Spread out over 17 days, this year’s Main Slate lineup included a spate of adaptations, featuring films based on literary fiction, a young adult novel, 19th-century journals, and even a Russian fable. Those that weren’t explicitly book-based contained characters with literary vocations working through their craft, rendered in delicious ways by filmmakers as they transposed the struggle between fact and fiction. Here are a selection of some offerings at the festival, which runs through October 16.

Saint Omer (November 23)

Over the past few years, French-Senegalese filmmaker Alice Diop has been steadily composing documentaries with an observational style, which she brings to her fiction debut. Saint Omer, a nominal courtroom drama, is a multifaceted and astounding gem of a film, posing moral and political quandaries that generate a wealth of intellectual and emotional consequences for viewer and character alike.

Laurence Coly (Guslagie Maland), a young African woman studying in France, is accused of murdering her 15-month-old daughter. The subject matter is sensational, and true (based on the 2016 trial of Fabienne Kabou), but Diop forgoes the sordid elements to create a sophisticated and contemplative drama that draws additional force by adding another character through which to view its subject: Rama (Kayije Kagame), a professor and author who’s attempting to understand Laurence, the subject of her upcoming book, and winds up finding parallels to her own life.

The film is composed of variegated textures—Rama’s flashbacks to childhood with her mother, exterior shots of the town of Saint Omer, a clip from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Medea, documentary-style home videos—which expose the filmmaker’s influences while enriching the text. The cogency of Saint Omer’s cinematic language rubs up against the opacity of its central character. Rama, and thus Diop, don’t quite defend this unknowable woman’s actions so much as they respect her silence, granting access to her humanity.

A Couple (October 19)

Based on the diaries of Sophia Tolstoy, A Couple similarly gives voice to an unheard woman. Married to the War and Peace author at a young age, Sophia worked for years as Leo Tolstoy’s copyist and cared for their 13 children, a duty, she notes, of which her husband never once deigned to relieve her.

In this carefully composed work, French theater actress Natalie Botefeu brandishes her voice as Sophia, delivering booming diatribes or more measured, somber soliloquies detailing her marriage. Sophia was a known diarist, and the speeches capture her eloquent deliberation on everything from maternal sacrifice, her husband’s petty jealousies, and his harsh critiques (“There is a mistake in every person”).

Through these extended scenes, which may seem more fitting for a play, Wiseman establishes a rhythm cultivating drama in the quotidian. The succession of monologues is intercut with shots of the garden where Sophia strolls, the serene botanical elements providing respite from her distressing anecdotes while foregrounding the nourishing realm of the feminine. In the past, Wiseman employed his methodical, patient scrutiny to excavate institutions such as high school, city government, and The National Gallery, and what emerges in A Couple is not only a poignant rebuke of a towering literary figure, but also a modern probing into the notions of marriage.

White Noise (December 30)

Writer/director Noah Baumbach does the unthinkable in adapting Don Delillo’s “unfilmable” novel, but was it really so impossible? The iconic and era-defining 1985 book—which side-eyed a specifically American deadening of the soul—is heavy on the dialogue and ready-made for speechifying, while its allusions to consumer culture and technology feel wholly suited for mise en scene, a set designer’s dream. White Noise the movie makes a commendable effort on both accounts, but the adaptation tempers the source material’s sardonic tang, transposing it to the near key of farce.

Baumbach magnanimously truncates the story—a toxic disaster upends the lives of Jack Gladney, professor of Hitler studies, and his family in a small college town (which appears to be in Ohio)—shifting and combining elements until they fit into a neat 138 minutes. The world of academia is short-shrifted (Don Cheadle is winning as colleague Murray Suskind), while home life is prioritized. Baumbach, after all, is one of contemporary cinema’s foremost bards of family dysfunction, and one of the high points of White Noise is the choreographing of the Gladney family, a “cradle of misinformation.”

The actors playing the precocious sons and daughters are particularly effective at enlivening the dialogue, much of it preserved from the book, while Adam Driver, as the central character, heightens it with his outre persona. Shedding Jack’s abysmal self-esteem, he unexpectedly comes to possess a sense of an everyman-hero, evoking, of all people, Tom Hanks. The middle section, taking place at a disaster camp during the airborne toxic event, is partially responsible. Effectively a mini-disaster flick, it plays like 80s Spielberg pastiche. Invoking a sense of marvel in the face of death, the unexpected and inspired addition of movie-magic is the one part of White Noise that enhances DeLillo’s text.

Bones and All (November 24)

Oscillating from teen romance to vampire horror to dusty road picture, Bones and All follows a pair of cannibalistic lovers across the US during the Reagan Era. Director Luca Guadagnino (Call Me By Your Name) tends to populate his worlds with people driven by passion over reason, and this premise works to marvelous effect in this adaptation of Camille DeAngelis’s YA novel of the same name. Handling the feelings and motives of adolescents, Guadagnino truly excels, lending dramatic heft to a straightforward story of human loneliness, infusing beauty into the grotesque, and teasing out every violent stunner of a sunset to boot.

Abandoned by her father, Maren (Taylor Russell), an “eater,” sets out to find the mother she never met and encounters more of her ilk, including a new beau (played by Timothée Chalamet) along the way. Bones and All earnestly traffics in unremarkable themes—self-acceptance, perseverance, preaching a gospel of love in the name of any hang-ups—and continues the ancillary mission started by Nomadland to reclaim the squalid joys of transient van-life and engender it ripe with possibility. But just as the film’s throes of puppy love threaten to smother you, the brazen savagery of its violence slaps you awake—if the sprays of blood and muscle tendon don’t get you, the sound of gnawing will.

The Eternal Daughter (October 10)

Writer and director Joanna Hogg extends the universe of her previous autobiographical works, The Souvenir Parts I and II, with this biscuit of a film—slender and sweet, tidily wanting—concerning two of its central characters. Julie, a filmmaker, takes her elderly mother on a birthday trip to a stately country inn where her mother once lived as a young girl. In a fanciful stroke of genius, both parts are played by Tilda Swinton, alternating between daughter’s stammering eagerness and mother’s worn politesse as they fuss and tiptoe over trifles, masking their true concerns.

As places, homes tend to hold a surfeit memories for their former inhabitants, but the characters in The Eternal Daughter run into a bit of trouble unleashing the torrent of the past, evoked throughout the setting and charged with a reliably British spookiness, a la Henry James. The interiors are richly textured with dapper Gothic finery while the woodsy outdoors are caked in a dense fog and damp chill. Julie’s attempts at sleep and writing are interrupted by whipping drafts and unidentifiable clatter, despite being the hotel’s only occupant.

The film often feels like an exercise in formal craft. It doesn’t burrow deep, and one wonders whether that’s a flaw or feature—a touch of concealment is exactly what this chic ghost story requires. Balancing tone and plot, Hogg has crafted something of lean resonance that invites the viewer’s inspection, much like the best novellas.

The Novelist’s Film (November 4)

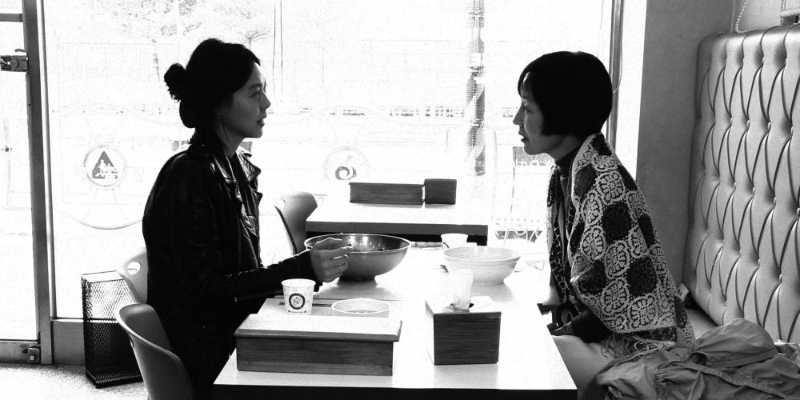

South Korean auteur Hong Sang-soo graces the festival again with not one but two films. For the uninitiated, the ferociously prolific director (Right Now Wrong Then, The Day He Arrives) is an efficient minimalist who constructs sprightly interpersonal dramas, the spare plotlines of which run counter to the myriad interpretations they conjure. Walk Up, which takes place in a three-story apartment building, uses an elliptical, time-compressing narrative that makes you wonder what’s real and what’s not for an aging filmmaker (Kwon Hae-hyo). Meanwhile, lacking temporal intervention,The Novelist’s Film is a breezy and undemanding depiction of the creative process.

Outside of Seoul, a successful author named Junhee (Lee Hye-young) has a series of planned and chance encounters with old and new friends, which fatefully enable her to meet a famous actress (Kim Min-hee). They decide to make a short film together, which is partially revealed toward the end. Hong typically depicts male creatives, often using them as his avatar, but with this film he paints a delicate yet incisive portrait of a spiky female writer. It’s a gentle slice of life that captures and prioritizes its banal ebbs and flows—eating a meal, drinking with strangers, walking the long way—that are inextricable from the makings of art.